Welcome to Jurassic Snark: Thinking about the 'new' Gawker and taking an axe to UnHerd on hatchet jobs...

A three star newsletter edition from a one-star person.

My favourite bad review is apocryphal. For years I laboured under the dim illusion that Charles Shaar Murray’s review of Yes’ debut album Yes simply read, “No.” In fact — one of a series of one-word dismissals by Murray — it was actually a more diffident “Maybe”. Still, at least we still have his brickbats for Bionic Boogie’s disco dud Cream Always Rises To The Top (“And shit still floats…”) and Lee Hazelwood’s Poet, Fool or Bum (“Bum”).

Yesterday, UnHerd (“Zero stars: As appealing as cow shit.”) ran a piece by Dorian Lynskey titled The dying art of the hatchet job. The premise was that truly biting critical assessments are endangered because they cannot survive the inevitable kickback on social media. Lynskey defines what he sees as the common social media — basically Twitter — responses:

Now critics are often up against readers who resist the very notion of criticism. A few popular lines of attack pop up regularly.

There’s faux-objectivity: You said this movie wasn’t funny but I laughed, ergo it is you are factually wrong and unprofessional.

Taking offence: How dare you imply that everyone who likes this movie is a tasteless dolt?

Assumption of bad faith: You’re only saying this for clicks and notoriety.

Character assassination: You’re a vindictive killjoy who’s no fun at parties. Moral disapproval: Why would you waste your precious time being mean about something when you could be praising something else?

Some people mix and match these accusations into strange hybrids like the schoolmarm-turned-troll:

Why can’t you be more positive, you dumb piece of shit?

The ‘now’ is interesting. A glance at music paper letters pages from the era when Murray was first making his way quickly makes it clear that readers had the same objections to critical reviews then. The difference is that social media removes the filter of a letters page editor and brings critics into direct contact with just how many people think they’re dickheads.

To further support his idea that we live in an era where only soft-hearted, soft-headed, soft-soaped reviews are ‘allowed’ Lynskey reaches for the words of one of the most unbearable authors in the world: Matt Haig. Most recently seen dishing up reheated portions of chicken soup for the soul in The Comfort Book1 (a title which should have come with pages you can chew), Haig tweeted:

There is so much jealousy of Sally Rooney. If you don’t like her books, don’t read them. The great thing about books is there are lots. There have literally never been more books. Why spend your time dissing authors other people like when you could be championing ones you do?

But that’s Haig projecting his egg-shell ego onto Rooney, as Lynskey himself notes (“It’s ostensibly about Sally Rooney’s sceptics but implicitly about his own.”) Rooney appears to be a lot more resilient to harsh reviews. In a recent interview with The Guardian, she said:

It’s not my job to populate my books with particular types of characters that I imagine other people might find relatable. It’s my job to write about whatever comes into my head, to the best of my ability. If as a reader you want to exercise control over the kinds of things that are depicted in novels, try writing one. That’s what I did and it worked for me.

There’s a flintiness there that I can never imagine Haig, a man seemingly on a quest to turn the world into a permanent lukewarm bubblebath, ever exhibiting. Haig’s ‘Eeyore with a book deal’ act is a perfect example to bolster Lynskey’s argument but he’s an outlier, a performatively sincere voice in a social media soup of irony and dead-eyed reviews.

The hatchet-job is not dead, it’s just that it is no longer the preserve of a small bylined elite. Instead, pompous authors, ‘thought leaders’, and public intellectuals (leather elbow patches and all) can be shot down by a single Twitter reply where once we’d be subjected to a months-long fax battle between Julie Burchill2 and Camille Paglia over which of them is more unbearable (VAR says: It’s a draw).

Lynskey’s hypothesis is that “hypersensitivity to critical voices has been compounded first by the ugly intensity of politics and then by the pandemic.” But I think this is ahistorical. From Listzomania in the late-19th century to the piss-drenched aisles of Beatles and Stones gigs through to the social media streetfighters of the One Direction and BTS stans, fandom has always come with an intense dislike for critics.

The notion that you can’t write a hatchet job now is close to “if you say you're English these days, you'll be arrested and thrown in jail”. You can write whatever you want — the newspapers’ comment sections are testament to that — but you can’t do so without a response, sometimes a very intense response, from people who don’t agree with you. That response was always there, it just wasn’t given a platform by the publishers of magazines and producers of chin-stroking late-night review shows.

Lynskey undermines his own argument by discussing two recent examples of hatchet jobs that flew: Becca Rothfield’s Sally Rooney anti-rave in The Point and Lauren Oyler tearing strips off Jia Tolentino’s essay collection Trick Mirror in The London Review of Books.

He suggests that Rothfield was helped in getting away with her hatchet-job by the fact that “smaller journals can be a little spicier,” but Oyler has often fired off critical takedowns and she’s done it for big publications. She could do that because she’s not afraid of social media. She’s so unafraid of it, in fact, that it plays a central role in her debut novel Fake Accounts.3

In an interview with The End of the World Review newsletter, Oyler talked about the art of the critical review:

There’s a line of thinking that says critics shouldn’t write negative reviews4, and if they don’t like a book they should spend their time highlighting work they do like, but I think that ignores how the publishing industry works, and how magazines work: They have to cover the ‘big books’ even if the books aren’t very good. I’m not going to do a long negative piece about a writer nobody has ever heard of because that’s cruel and doesn’t serve any sort of greater purpose.

I don’t have any ethical quandaries about the negative reviews I’ve written — those authors exist as they are going to exist and nothing I say is going to change that… when I do those negative pieces, I try to make them relevant first to someone who is never going to read the book and feels that the critical discourse around it is leaving out something major.

In the same interview, Oyler dismisses the rage that some of her brickbats have sent flying back at her:

Sometimes people say, “Oh. My. God. These people are saying such mean things about you.” I’ll respond, “I am pretty sure I saw everything everyone said about me, and it’s not that bad. It’s fine.” It’s not that bad!

While Lynskey came up in the twilight era of the printed music press, Oyler is a product of the discourse and she’s not afraid of what lurks in the shadows.

Lynskey writes that he found the reaction to Scott Tobias’ critical essay about Shrek “extraordinary” and concludes that the writer’s crime was “hating an old, animated movie about an implausibly Scottish ogre and his donkey friend.5” But that’s to assume that all the ‘anger’ on social media was a) real and b) a defence of Shrek as a work of art.

The Shrek review went viral because The Guardian tweeted it out in a way that made it seemed like a weirdly petty one-off rather than part of a series, many extremely online people watched the movie during their childhoods, and Shrek is just a very memeable film. All the reaction to Tobias’ article really proves is that there is a combination of brutal serendipity and boredom that can catapult a writer into the heart of social media’s unforgiving Sauron eye.

Oyler shows that you can write brutal reviews in the age of social media, you just have to be willing and ready to hear that you’re stupid and wrong. Lynskey says:

It’s hard to imagine a review of a major artist as famously scathing as Greil Marcus’ take on Bob Dylan’s 1970 album Self Portrait (first line: “What is this shit?”) in the age of Twitter. You want to take an axe to Korean boy band BTS and their ride-or-die followers? Lock your account first.

Sure slagging off BTS6 is high risk by social media standards but it’s hardly up there with Sid Vicious beating Nick Kent with a bicycle chain. I received a healthy number of violent (and detailed) messages when I gave Chris Brown’s album Fortune zero stars back in 2012 on the basis that he’s an unrepentant piece of shit who violently abused a woman. It hasn’t deterred me from writing critically since. A Marcus-style mauling of a major artist is still possible, you just have to know what you’re doing.

When Lynskey writes…

The instinct to abuse critics is justified by the idea that it is “punching up” at elitist gatekeepers. But unlike Siskel and Ebert, modern critics are neither famous nor wealthy nor powerful. They may have influence en masse, via review aggregators such as Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic (there is safety in numbers), but the days when one critic could make or break a movie, album or anything else are long gone. Yet fans still see them as dream-crushing monsters from which million-selling musicians and billion-dollar movies must be defended at all costs.

… it feels like yet another journalist’s complaint that it’s no longer 1978. Critics with major platforms may not feel powerful but they seem powerful to fans, who are not required to know the ins and outs of journalism’s penny-pinching, freelance-kicking year-round exploitathon.

I’m also quite tired of everything from insults to actual death threats being thrown into the same big bucket marked “abuse”. It’s all too easy for critics, columnists and other assorted opinion havers to mark anyone without a byline as an abuser or a troll. Life’s hard in the NFL

In fact, Lynskey argues that people annoyed by hatchet-jobs or even mildly-negative critics are “[lumping them] in with the trolls and ‘haters’ who plague your timeline.” He continues:

There are, of course, some contrarians, bullies and attention-seekers who have built a brand on performative contempt but they are not typical.

I disagree with that but then I would since one of the central themes of this newsletter from the very beginning is that contrarianism and performative contempt are central to British and American journalism.

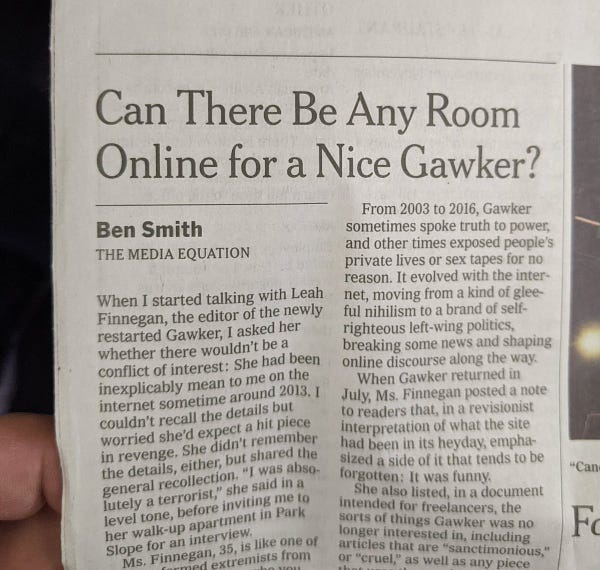

Shortly after I’d finished Lynskey’s piece, I read New York Times media columnist Ben Smith’s profile of the ‘new’ Gawker and its editor Leah Finnegan (If Gawker Is Nice, Is It Still Gawker?)

The original Gawker — like NME before it Gawker has had several eras and veterans of each argue for their own as “the best” — was only two years old when I first became a professional journalist, plying my trade for Pensions World magazine. And while I was stuck in a sickly green building across from East Croydon train station, I could imagine I was in the middle of New York media by poring over the delicious poison pumped out by Gawker.

The central question of Smith’s piece, distilled in that typically New York Times drier than a cracker in the desert headline, is whether the ‘nice’ Gawker under Finnegan’s editorship and Bustle’s ownership7 should carry that name after its ship of Theseus-style deconstruction and reconstruction.

After detailing Finnegan’s notes for new Gawker writers that say it is “no longer interested in… articles that are ‘sanctimonious’, or ‘cruel’”, Smith — who highlights in the piece’s first paragraph that Finnegan once slammed him — says:

That marks a notable change from [Finnegan’s] time as the features editor of Gawker, in 2015, when her indiscriminate brutality included describing an infant as “hipster scum.” That one prompted a rebuke at the time even from Gawker’s rather coldblooded founder, Nick Denton, who wrote in the site’s comments section that the headline was “just nasty” and that she would regret it. Ms. Finnegan responded that she was speaking “my truth.” (Asked about the new version of the site he founded, Mr. Denton told me in a text: “Finnegan’s take on Gawker not my thing, back in 2015. No opinion on the 2021 revival.”)

Swimming as we are deep in the cursed waters of 2021, when Times (of London, if you insist, American readers) columnists openly laugh at the death of a young woman and call in print for the removal of ethnic minority status for Gypsy, Romany and Traveller people, a crass joke about a baby who was hardly glued to Gawker at the time seems almost mild. Similarly, describing Nick Denton as “rather coldblooded” is an outrageous understatement given that he’s like Nosferatu if the vampire occasionally dined at Nobu.

A quote from Smith’s piece from his former colleague, BuzzFeed managing editor, Sarah Yasin…

The internet is both too mean and too nice for Gawker now. If you’re mean, you have to be super edgelord mean, or else you have to be super earnest.

… has got a lot of play on media Twitter (one of the most cursed corners of an already cursed site). I can see why; it’s a good line that sounds profound until you start to pull at the edges a little.

Broad statements work well when you’re writing online — Shrek is awful, ‘new’ Gawker cannot survive, hatchet-jobs are dying because of social media — but a lot of the time they crumble if you subject them to close scrutiny. ‘New’ Gawker doesn’t have to be old Gawker to succeed. In fact, if it attempted to do the same things again it would certainly fail.

What counts both for ‘new’ Gawker and critics who want to write truly stinging reviews is bravery. You don’t get to pull up the drawbridge as a writer now. The era of being safely behind your byline, dealing only with a few angry green-ink obsessives bombarding the letters page is long gone. And I’m glad.

I’d take the final line of Lynskey’s UnHerd piece…

It’s not that I long for an epidemic of gleeful brutality but I will always cherish the right of critics to express their hate, hate, hate in the ultimate service of what they love, love, love.

… as a challenge if I didn’t already write about things I hate on a daily basis.

I don’t think the hatchet-job is dead any more than I think that ‘new’ Gawker is destined to fail for not being sufficiently vituperative. What I do think is that when writers pine for the old days, they’re often pining for a time when they could set the tone, define the argument, and ignore their own critics, safe in the knowledge that only they and their friends had access to a megaphone.

It got an enjoyably unrestrained critical shellacking in Private Eye, where hatchet jobs are still very much welcome.

Burchill’s legally ruinous attacks on Ash Sarkar last year showed just how poorly her brand of acid bullshit translates to the high stakes world of social media.

Which itself was the subject of a cold-eyed appraisal in the LRB.

I’d call it Haigism but I don’t want to salve his ego.

This is a minor quibble here but Shrek’s Scottishness is hardly implausible in a world where a donkey can marry a dragon and a cat is an expert swordsman. Also: Since we never see Scotland in the world of Shrek it may just be an accent that sounds Scottish but is really just the way ogres speak. Yes, I’ve over-thought this…

And why would you want to be mean to those beautiful boys with their lovely songs? Hi BTS Army!