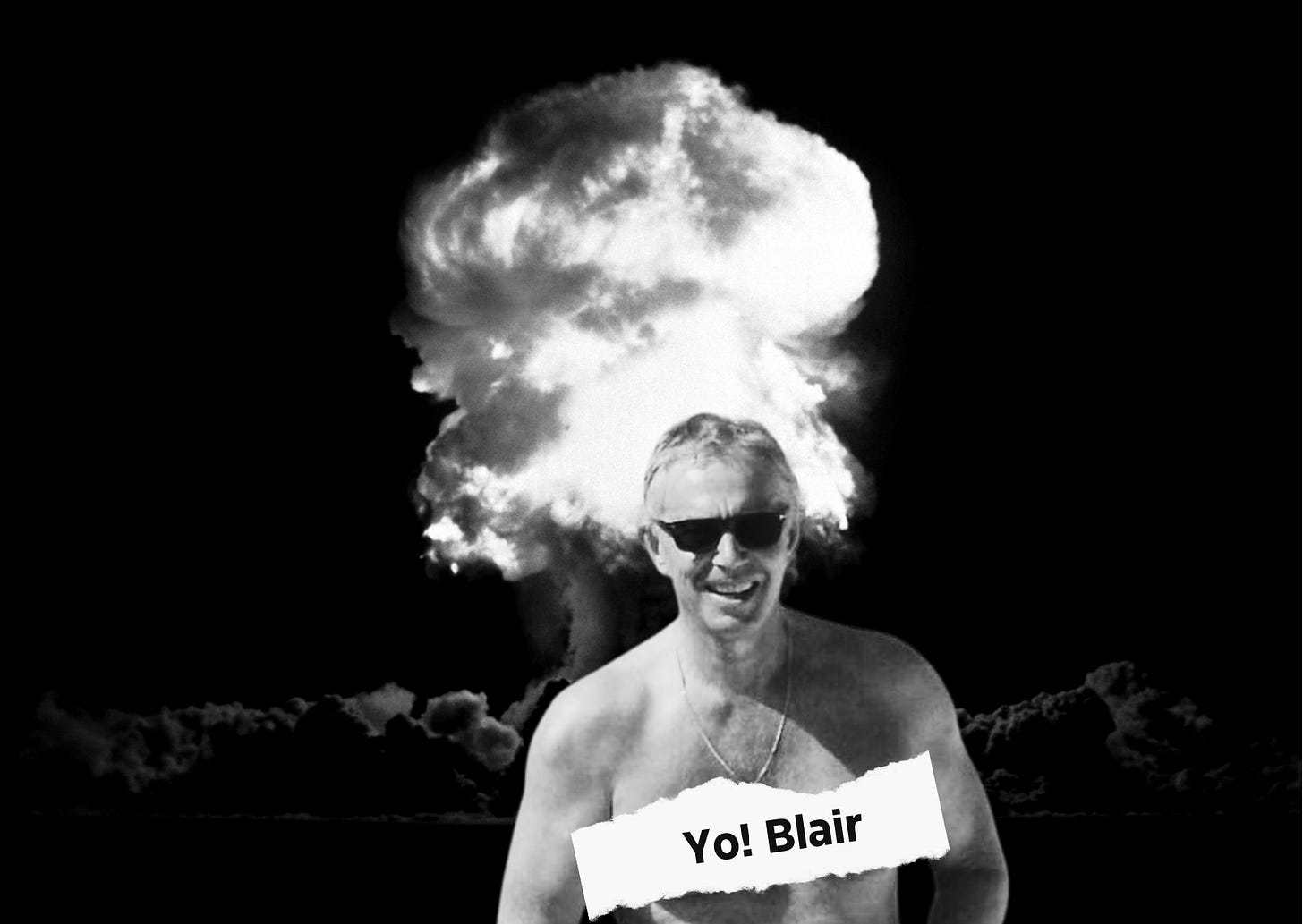

Tony Blair brand blinkers (20-year guarantee)

The British media wants you to think it's learned the lessons of Iraq; it hasn't...

Previously: Bullied Broadcasting Corporation

Twenty years ago it was battered over Iraq, now it's bruised over the Lineker 'affair' and leaked emails show the BBC has been bullied again.

I didn’t have a proofreader today so any typos are deliberate and designed to make you question the tyranny of the author or something…

The international criminal court (ICC) in The Hague has issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin for overseeing the abduction of Ukrainian children, sending Russia another significant step on the path to becoming a pariah state.The Guardian, 17 March 2023

Mehdi Hassan: … looking back now should [Tony Blair and George Bush] have faced some consequences for the disaster that was Iraq?

Hans Blix: In principle, yes. I think that has been felt ever since the First World War and, after the Second World War, you had, of course, the Nuremberg tribunals. And now, with the Russians invading Ukraine, you have many people acting to set up collection of evidence for some kind of trials after the end of the Ukraine War. So, I think the principle, the rule in the United Nations charter that you are not allowed to use force against territorial integrity and independence of other states that should have a corroboration in a penalty view.

MH: You mention ‘principle’; obviously in reality, in real life, it’s not going to happen but I’m just wondering in theory, in principle, are you saying you would have liked to see a George Bush, a Tony Blair put in front of The Hague like any other person who has defied/violated international law; accused of war crimes?

HB: I think in principle: yes. And I think they would not come and nor would Putin come before a tribunal. Nevertheless, holding a tribunal and going through the evidence would be of value, yes. We hear very much from the Western world about the ‘rules-based international order’; now that is the one that US and UK, and the others broke in 2003. The Mehdi Hasan Show, MSNBC, 16 March 2023

On the one hand, Hans Blix — the 94-year-old former politician, diplomat, and UN chief weapons inspector, a post that saw him navigate the aftermath of the Chornobyl disaster as well as the rush to war with Iraq — believes Bush and Blair should, in the best of all possible words, find themselves at the International Criminal Court in the Hague. On the other: Andrew Castle — former (British no.1) tennis player turned LBC/BBC presenter — says:

I’m sick and tired; I can’t believe that… my life has come to a point where what happened in Iraq has to be equated with what’s happening in Ukraine. It is an absurdity! You have to look at each and every one of these things in isolation. Did everything that every country has ever done… was this perfect or right? Absolutely not. It’s horrifying, morally repugnant, it shouldn’t have happened — all of those things. But because they happened now we give a free pass to Putin? I can’t even understand the leap from one to the other… Call it the Castle Doctrine: International politics are like a series of boss battles in a computer game; different levels you play that are only related to each other through some of the non-player characters and brands plastered over the thing. He “can’t even understand the leap” from Putin to Bush and Blair? What can he understand beyond match points and how to angrily reply to various tethered-goat callers set up to be harangued by his producers?

It is not necessary to be a fan of the war criminal Vladimir Putin to suggest that Tony Blair and George Bush also belong in that category. The 20th anniversary of the Iraq War is the catalyst for their actions being scrutinised again; they have spent most of the years since further enriching themselves; with Blair treated as a source of international wisdom and Bush redefined as a cuddly comedy act; a member of the Obama sidekick troop.

The view that the Iraq War was illegal — a war of aggression — is not one that has just coalesced in hindsight, as a result of having witnessed its brutal and fatal realities. I was in my first year at university when the invasion began; we marched against it before Tony Blair turned his eyes away from more than a million people on the streets of London.

The official UK government legal opinion on the military action was against it before it was suddenly for it (with caveats). Lord Goldsmith, the Attorney General, wrote a memo to the Prime Minister on 30 January 2003:

In view of your meeting with President Bush on Friday, I thought you might wish to know where I stand on the question of whether a further decision of the [UN] security council is legally required in order to authorise the use of force against Iraq… I remain of the view that the correct legal interpretation of resolution 1441 [the final security council decision on Iraq] is that it does not authorise the use of force without a further determination by the security council…

… My view remains that a further [UN] decision is required. The document — released to the Chilcot Inquiry — includes handwritten notes in the margins from David Manning, Blair’s chief foreign policy adviser, (“Clear advice from attorney on need for further resolution.”) and Blair himself, who scrawled — seemingly in frustration — “I just don’t understand this.”

A further note from an unnamed aide reads: “Specifically said we did not need further advice [on] this matter.”

What Goldsmith actually thought didn’t matter though; it was what he could produce to justify a decision that was already locked in that counted.

On 31 January 2003, Blair met Bush in Washington again. Minutes taken by Manning at the time record Bush telling Blair that military action would take place regardless of whether a second security council resolution was secured. Manning notes: “The prime minister said he was solidly with the president.” The view of the government’s top legal advisor was irrelevant.

The previous July, Goldsmith had warned Blair that on the question of whether using force against Iraq could be considered ‘self-defence’, “the key issue [was] whether an attack [was] imminent.” Hence all the heavy importance placed on the 45-minute dossier.

Curiously by 7 March 2003, Goldsmith had changed his mind and told Blair that a new resolution might not be needed, but he still caveated this ‘new’ view with a warning that Britain would risk being indicted before an international court.

The 13 pages of legal advice included a list of six reasons why the Prime Minister Blair could be in breach of international law. Ten days later, Goldsmith published a note saying invasion would be lawful; it contained none of the previous warnings. However, the new analysis still concluded that “regime change [could not] be the objective of military action”.

The Chilcot inquiry didn’t consider the legality of the Iraq War; the man, Sir John Chilcot said he had not “expressed a view” and that the question could only be resolved by a court. But the report did say that the circumstances in which the government ‘decided’ that there was a legal basis for military action were “far from satisfactory”.

Goldsmith did not present his report to ministers in cabinet; instead, he gave a short verbal explanation, based on a short written response to a parliamentary question, which was handed around before the discussion was quickly moved on. In the new BBC podcast series Shock and War: Iraq 20 Years On, Clare Short — who was then Secretary of State for International Development — says:

That really stunned me; when he came and read out this thing they’d put in a parliamentary answer saying there was legal authority… [it] was right at the end and they put these two sheets of A4 around, in front of everybody, and he started reading it out. And I said, “We can read it, you don’t need to… but tell us what happened? Did you change your opinion?” Because I still believed that the legal opinion was still a really big issue and barrier. And they said, "Shh! Clare be quiet. We don't want any discussion."Chilcot concluded that the cabinet had been asked for a rubber stamp on a decision presented to them as a done deal. She resigned two months later after the war had started; Robin Cook — the former Foreign Secretary, who had been demoted to Leader of the House in the 2001 post-election reshuffle — resigned on 17 March 2003, the day Goldsmith presented his second opinion.

The Chilcot report says:

Given the gravity of the situation, cabinet should have been made aware of the legal uncertainties. The report points out that no minister asked Goldsmith to explain why he had so drastically changed his advice in the space of 10 days. Chilcot says:

There was little appetite to question Lord Goldsmith about his advice and no substantive discussion of the legal issue was recorded. While Congress gave legal cover to Bush with the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 act, Ramsay Clark — Lyndon B. ‘Jumbo’ Johnson’s Attorney General, who supervised the drafting of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and Civil Rights Act of 1968 as well as attempting to jail many Vietnam War protestors. — wrote in a letter to the UN Secretary-General that:

If President Bush believed it was "diplomacy", which maintained genocidal sanctions against Iraq for twelve years that failed, rather than an effort to crush Iraq to submission, then why didn't he use "nine months of intense negotiations" to avoid a war of aggression against Iraq? He was President for nearly twenty-seven months before the criminal assault on Iraq, he apparently intended all along. Iraq was no threat to anyone.

What President Bush means by "intense negotiations" includes a threat of military aggression with the example of Iraq to show this in no bluff. The Nuremberg Judgment held Goering's threat to destroy Prague unless Czechoslovakia surrendered Bohemia and Moravia to be an act of aggression.

… In March 2003 Iraq was incapable of carrying out a threat against the U.S., or any other country, and would have been pulverized by U.S. forces in place in the Gulf had it tried.

More than thirty-five nations admit the possession of nuclear, chemical and/or biological weapons. Are these nations — caput lupinum — lawfully subject to destruction because of their mere possession of WMDs? The U.S. possesses more of each of these impermissible weapons than all other nations combined, and infinitely greater capacity for their delivery anywhere on earth within hours. Meanwhile, the U.S. increases its military expenditures, which already exceed those of all other nations on earth combined, and its technology which is exponentially more dangerous.

The U.N. General Assembly Resolution on the Definition of Aggression of December 14, 1974 provides in part:

Article 1: Aggression is the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another State;

Article 2: The first use of armed force by a State in contravention of the Charter shall constitute prima facie evidence of an act of aggression;

Article 3: Any of the following acts ... qualify as an act of aggression:

(a) The invasion or attack by the armed forces of a State of the territory of another State, or any military occupation, however temporary, resulting from such invasion or attack;

(b) Bombardment by the armed forces of a State against the territory of another State or the use of any weapons by a State against the territory of another State;

(c) The blockade of the ports or coasts of a State by the armed forces of another State;

(d) An attack by the armed forces of a State on the land, sea or air forces, or marine and air fleets of another State.

If the U.S. assault on Iraq is not a War of Aggression under international law, then there is no longer such a crime as War of Aggression. Clark had previously accused Bush’s father George H.W. Bush and his generals in the First Gulf War of “crime against peace and war crimes”; a harder case to make given that Saddam Hussein had invaded Kuwait.

Later, when Hussein was on trial, Clark was one of two non-Arab lawyers who joined a panel of 22 to defend him in his trial before the Iraqi Special Tribunal. It added to a wild roster of former clients for Clark including Radovan Karadžić; survivors from the assault on the Branch Davidian compound; Rwandan genocide leader Elizaphan Ntakirutimana; and the Nazi war criminal Jakob "Jack" Reimer. That roster made Clark easy pickings for Christopher Hitchens:

From bullying prosecutor he mutated into vagrant and floating defense counsel, offering himself to the génocideurs of Rwanda and to Slobodan Milosevic, and using up the spare time in apologetics for North Korea…But Hitchens at his most thirsty for war was pretending that Clark — among the weaker and more undermined voices against the war — was an outlier.

For example, Professor Marjorie Cohn of Thomas Jefferson School of Law wrote in an extended argument for Donald Rumsfeld being tried as a war criminal that:

Rumsfeld's sin was not in failing to develop a winning strategy for Iraq. There is no winning in Iraq, because we never belonged there in the first place. The war in Iraq is a war of aggression. It violates the United Nations Charter which only permits one country to invade another in self-defense or with the blessing of the Security Council.

Prosecuting a war of aggression isn't Rumsfeld's only crime. He also participated in the highest levels of decision-making that allowed the extrajudicial execution of several people. Willful killing is a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions, which constitutes a war crime. In his book, Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib, Seymour Hersh described the "unacknowledged" special-access program (SAP) established by a top-secret order Bush signed in late 2001 or early 2002. It authorized the Defense Department to set up a clandestine team of Special Forces operatives to defy international law and snatch, or assassinate, anyone considered a "high-value" Al Qaeda operative, anywhere in the world. Rumsfeld expanded SAP into Iraq in August 2003.

But Rumsfeld's crimes don't end there. He sanctioned the use of torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, which are grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, and thus constitute war crimes. Rumsfeld approved interrogation techniques that included the use of dogs, removal of clothing, hooding, stress positions, isolation for up to 30 days, 20-hour interrogations, and deprivation of light and auditory stimuli. According to Seymour Hersh, Rumsfeld sanctioned the use of physical coercion and sexual humiliation to extract information from prisoners. Rumsfeld also authorized waterboarding, where the interrogator induces the sensation of imminent death by drowning. Waterboarding is widely considered a form of torture.And who backed, endorsed, and encouraged those decisions? George Bush, with the tacit approval of his friend Tony Blair.

Their mutual friend Rupert Murdoch was also very much on board. In February 2003, the month before the war began, he told the Australian magazine, The Bulletin, that Blair was “extraordinarily courageous and strong” and continued:

We can't back down now. I think Bush is acting very morally, very correctly, and I think he is going to go on with it. The fact is, a lot of the world can't accept the idea that America is the one superpower in the world…

… The greatest thing to come out of this for the world economy, if you could put it that way, would be $20 a barrel for oil. That's bigger than any tax cut in the any country.When you’re a billionaire, you don’t need to worry as much about saying the quiet bit loudly. The Sun’s front-page take on WMDs in Iraq was the subtle and nuanced headline on 25 September 2002:

He’s got ’em, let’s get him

While a few dissenting columnists were allowed — Simon Jenkins and Matthew Parris (Are We Witnessing the Madness of Tony Blair?) among them — Murdoch’s papers (almost) universally supported the war in Iraq (it’s only “almost” because of one holdout, the plucky Papua New Guinea Post-Courier). The New York Times profiled ‘Mr Murdoch’s war’; the piece begins:

On the first day of the war with Iraq, Rupert Murdoch watched the explosions over Baghdad on a panel of seven television screens mounted in the wall of his Los Angeles office, telling friends and colleagues over the phone of his satisfaction that after weeks of hand-wringing the battle had finally begun.Warmongers don’t work with anvils and hammers; they use newspapers, radio stations and TV networks.

The Observer was (in)famously in favour of the war with David Aaronovitch one of the loudest cheerleaders on its squad. A selection of his columns on the topic in chronological order reveals the mixture of bravado, self-satisfaction, and panic he offered:

Thank the Yank (9 Mar 2003):

I don't pretend to understand what the French and Germans are up to strategically. They cannot stop the war, but perhaps their target is to stop the war after that. If so, the Iraqi people are as much a victim of their power politics as they would be if the US were to invade then hand them over to some undemocratic successor. I do know, however, that the French way - the anti-American way - will make it much more difficult to get the world's most powerful nation on-side for the great tasks that face us. You can hear the complaints already.What would change my mind on Iraq? (1 Apr 2003)

…you cannot easily answer in an actuarial manner. How do you balance this many dead civilians against the thousands still to be killed in Saddam's prisons or in his suppression of rebellion? This many soldiers versus the thousands still to die as the regime (at some future date) implodes? This much terrorism provoked, versus this much democracy encouraged? So, whatever the amount of death and mayhem, it could be years before anyone on either side of the argument can credibly claim vindication. Although, as the voice whispers, if Donald Rumsfeld really is an idiot, Tony Blair really is a fantasist and I really am a cunt, it could be only weeks.All for one... (13 April 2003)

Iraq begins its new life with several advantages. It has not been comprehensively destroyed and it possesses a substantial natural economic asset. Nor is it regarded by its occupiers as a defeated nation, but as a liberated one.Those weapons had better be there ... (29 April 2003)

These claims cannot be wished away in the light of a successful war. If nothing is eventually found, I - as a supporter of the war - will never believe another thing that I am told by our government, or that of the US ever again. And, more to the point, neither will anyone else. Those weapons had better be there somewhere.A bloody delusion (28 Sep 2003)

I can scarcely bring myself to point out that all of the measures of public opinion taken in Iraq since the invasion - however flawed - have shown that Iraqis believe the invasion was probably necessary, are critical that security and vital services are still not guaranteed, but are optimistic about the future. They do not seem, despite grievous American mistakes, to offer support for the idea of armed 'resistance'.The year Britain invaded Iraq - and tore itself apart (28 Dec 2003)

It is fashionable now to say that we were 'lied to' by our governments, but the truth surely is that they had grounds for their nightmare equation of dictator's weapons plus terrorists equals possible catastrophe. Saddam's long-term non-compliance with UN resolutions on inspection and declaration hardened their view, based on what might have been faulty intelligence, that there was something there. They had, after all, to be wrong once.Was I wrong about Iraq? (17 Feb 2004)

So much for WMD. For "liberal interventionists", however, the Iraq issue had another, more significant dimension. Wasn't war, in the end, the only way of bringing down the tyranny of Saddam, and wouldn't that war end in an Iraq - and a Middle East - that was safer and freer than before? On this, above all, was I wrong? If you care one way or another, I'll try to answer this next week…Was it worth it? Ask those who know (24 Feb 2004)

Now, nearly a year after the beginning of the coalition invasion of Iraq, something is beginning to be created, and it doesn't look like anything that anybody quite anticipated. It is more complex, more difficult, more beset by difficulties and tragedies than anyone who supported the invasion ever allowed before the war.So this is free Baghdad (9 Apr 2004)

So, of all the things we have done, the invasion may be bloody appalling, but it is the least bloody appalling thing of all. And the only thing that has offered hope.Now it's time for the war critics to move on (1 Feb 2005)

"The thing is, David," said the anti-war Labour politician in the hospitality room after the programme we had both just appeared on, "you're on a hook, and you can't get off." The "hook" was the logic of having supported the invasion of Iraq. You back the invasion to get rid of Saddam, so you must support an occupation, so - when it goes wrong - you must then endorse measures taken to suppress "resistance", and must go on to apologise for or excuse atrocities committed by allied forces ... and so on.We didn’t move on and neither has he; Aaronovitch moved to The Times in June 2005 and has only stopped writing columns justifying his position on Iraq because he’s finally stepped down from his spot there after 18 years. No doubt he’ll cover the 20th anniversary of the war on his hinted-at but yet-to-be-announced Substack.

This week’s edition of Politics Weekly UK, a Guardian podcast, made oblique mentions to ‘liberal’ columnists who supported the war but never let the name Aaronovitch be uttered; what an indignity for him, the former Eurocommunist son of communist parents to be airbrushed out of the picture.

The Guardian likes to pretend it was far better than its Sunday sibling, but while it did not row in behind the war so enthusiastically, it still played its part. In a leader column on 12 March 2003, it wrote:

… there is one thing Mr Blair cannot be accused of: he may be wrong on Iraq, badly wrong, but he has never been less than honest. Of course! He was a “pretty straight sort of guy”, right?

In an op-ed on the eve of war, Guardian columnist Timothy Garton Ash wrote that “one has the feeling that Blair is that kind of very decent Englishman who will always say no to drugs and never say no to Washington,” but spoiled it by sycophantically mooning over the Prime Minister’s parliamentary performance:

Over the last few weeks, the geopolitical west of the cold war has collapsed before our eyes. The twin towers of Nato and the European Union remain physically intact, but not politically. No one can know what the shape of the new world will be. As Tony Blair said in his magnificent speech to the House of Commons on Tuesday: "History doesn't declare the future to us so plainly." But we can already see three broad ideas competing for the succession to the cold war west. I'll call them the Rumsfeldian; the Chiraco-Putinesque; and the Blairite.How crass that “twin towers” echo was even then.

When the WMDs did not materialise, Garton Ash clumsily changed his act just like Aaronovitch, writing:

You may think Blair is a Bliar; I don’t. I’m sure he was convinced that Saddam had those weapons and therefore acted in good faith.“Good faith” is the most devalued currency in British media and politics; it has been near worthless tin since long before this century dawned.

I covered the BBC’s complicity in all of this and the crime perpetrated against David Kelly and his familiar in the previous edition. Andrew Marr’s words outside Downing Street should haunt him, the Ghost of Sycophancy Past:

Mr Blair is well aware that all his critics out there in the party and beyond aren’t going to thank him (because they’re only human) for being right when they’ve been wrong. He said that they would be able to take Baghdad without a bloodbath, and that in the end the Iraqis would be celebrating. … Tonight he stands as a larger man and a stronger prime minister as a result.In a piece for The New Statesman this week — The BBC needs to stop being its own worst enemy — Marr uses the word “Iraq” once. Its absence is second only to the complete invisibility of any thinking about his own role in the marketing of the military action.

Jonathan Freedland, who appeared on this week’s Guardian Politics Weekly UK podcast as the voice of reason to talk about what people got wrong back then, was not as slobbering. But in a column in the run-up to the war, he followed a long list of reasons it should not happen — and preceded a conclusion that the case had not been made — with “on the other hand” arse covering:

Tony Blair's opening line yesterday was a good one. He said that no one would have backed a war against al-Qaida on September 10; they would have waited until it was too late. He is right. Preventative action is always hard to justify, that is its nature. Critics are right to set the bar high, and to demand substantial proof of both Saddam's intent and capacity, but the argument - that a threat should be fought before, not after, it has done its worst - is not inherently contemptible.

In the Saddam case there are several clues to go on. He has past form, invading a neighbour and gassing Kurds within his own borders. Maybe he is a reformed character, forced to behave since 1991, but that record cannot be ignored. Second, it is at least legitimate to wonder why, if Baghdad has nothing to hide, it has fought so strenuously to keep inspectors out since 1998. Third, the lack of detailed knowledge of Saddam's arsenal cuts both ways. It is true that George Bush does not know whether Saddam has a box full of killer toys in the attic - but nor does the anti-war camp know that he does not. We are all working from information that is four years out of date. Of course we are: that's the root of this whole problem.Elsewhere the paper Julie Burchill, Colonel (ret.) of the Queen’s 15th Regiment of Hip Young Gunslingers, banged the drum: Why we should go to war:

"It's all about oil!" Like hyperactive brats who get hold of one phrase and repeat it endlessly, this naive and prissy mantra is enough to drive to the point of madness any person who actually attempts to think beyond the clichés. Like "Whatever!" it is one of the few ways in which the dull-minded think they can have the last word in any argument. So what if it is about oil, in part? Are you prepared to give up your car and central heating and go back to the Dark Ages? If not, don't be such a hypocrite. The fact is that this war is about freedom, justice - and oil. It's called multitasking. Get used to it!The Guardian and Observer had gone backwards. On Suez, the former wrote…

It is wrong on every count — moral, military and political. … and the latter, in a leader penned in part by its owner/editor David Astor, said:

We had not realised that our government was capable of such folly and such crookedness. After Chilcot, the British press almost universally — The Daily Mail opposed the war because, for it, Tony Blair was always more monstrous than Saddam — whole pretended it was a collection of innocent naifs taken for a ride by Blair, the sophisticated political lothario. The Sun, whose proprietor had drooled publicly about what good news the war would be for oil prices, squeezed out YouTuber apology tears:

Sir John Chilcot’s report did not accuse our former Prime Minister of lying about Saddam’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction. Yet Blair accepted dubious evidence of them without question, ignoring contradictions and warnings. He used them to sell the war to Parliament, the nation — and The Sun — with his silky oratory.In The Times, Aaronovitch It’s easy for Chilcot to be wise after the event and concluded:

Looking back, I wish we could have avoided going into Iraq. Not just because I’m squeamish about the consequences but because it would have meant we wouldn’t have lost our appetite for intervention when we needed it most — to stop Syria descending into hell and becoming the true disaster of our era.Yes, his main regret was that it made other invasions less appealing.

On the 10th anniversary of the war beginning, Jason Cowley, the editor of The New Statesman, wrote a very short retrospective column on how ‘the left’ responded to the rush to invade. His ‘favourite’ piece? A wet, hand-wringing bit of liberal bothsidesism from the increasingly unreadable Ian McEwan:

One of the best pieces I read on the eve of the invasion was by Ian McEwan, on the openDemocracy website, an anguished expression of honest doubt and ambiguity. “The hawks,” he wrote, “have my head, the doves my heart. At a push I count myself – just – in the camp of the latter. And yet my ambi – valence remains . . . One can only hope now for the best outcome: that the regime, like all dictatorships, rootless in the affections of its people, will crumble like a rotten tooth . . . and that the US, in the flush of victory, will find in its oilman’s heart the energy and optimism to begin to address the Palestinian issue. These are fragile hopes. As things stand, it is easier to conceive of innumerable darker possibilities.”For the 20th anniversary retrospective — when is the Hutton Inquiry Boxset with the b-sides and unreleased material being released? — Cowley has written a ‘long read’ for the paper about Royal Wootton Bassett. The small market town in Wiltshire gained its ‘royal’ as a propaganda move linked to its role during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as the place where planes bringing dead service people home landed. Cowley writes:

What we witnessed in Wootton Bassett during those four years of the repatriations was nothing less than an act of national commemoration. But it was unofficial, of the people and for the dead soldiers and their families; political leaders did not come and the royal family were not represented. “No one organised it, no one requested it,” the Royal British Legion’s former national president, Lieutenant General Sir John Kiszely, said. “It happened because it was the right thing to do.”One of the soldiers who died and returned to Wooton Bassett was Loren Marlton-Thomas, one of Cowley’s wife’s cousins; it’s an undeniable personal hook for the piece but there are still elements of it I find uncomfortable. Talking about dead service people and the emotions of those left behind is a quick way to sometimes cheap emotion for journalists; there will be a lot of that over the next few weeks as this 20th anniversary is analysed and unpicked.

There is a lot of unexploded journalist passive tense in Cowley’s writing:

The ultimate meaning of the Wootton Bassett repatriations remains ambiguous, however: the ceremonies of mourning venerated the dead soldiers without ever seeking to celebrate or claim as just the wars in which they died. The military was becoming increasingly politicised and British society more militarised – England footballers started wearing red poppies on their national team shirts and the names of the fallen were read out weekly in parliament; but the public was more reluctant than ever to support war-fighting interventions.The military becomes increasingly politicised; society more militarised; the public more reluctant to support “war-fighting interventions” (a truly wonkish way of elongating an easy three-letter word: war). Who made these things happen and why? That, in theory, is a journalist’s job to answer, just as it was meant to be journalism’s job to challenge the rush to war in 2003. But the idea that it was a failure of journalism that the war happened presumes that the bulk of the media didn’t want it to happen for both ideological and commercial reasons: War sells. People want to see the explosions, study the maps, and indulge in the psychic vampirism of sucking on other people’s grief.

Ironically, the most truthful reflection on the war and journalism doesn’t come from Cowley’s long read but a quick aside at the start of the publication’s weekend email newsletter. Will Lloyd writes, about interviewing General Lord Dannatt:

This week I interviewed a lord. Not just a lord either, a general too. Richard Dannatt has sent thousands of men into battle and negotiated with some of the most powerful politicians of the last 30 years. I found myself disagreeing with much of what he said about Britain’s involvement in Iraq, but I couldn’t quite bring myself to say so. Can you be cutting to a lord? It bothered me for days after we spoke. And then I realised: it was exactly this – ridiculous deference – that helped get Britain into that terrible mess in Iraq. Soldiers had too much respect for politicians. Politicians had too much respect for soldiers. As for journalists, most of them were MIA in 2003. We should all be more frank with each other, and say what we mean, in the moment. There was too much deference to power on the road to the Iraq War but the lessons have not been learned because the British media is still dominated by the same voices that failed then and the papers are still controlled by the same editors and proprietors by and large.

The unwillingness to draw a thread from Iraq to the conflicts of today and those that columnists like Con Coughlin in the Daily Telegraph are writing teasers for now (Bomb! Bomb! Iran!) is a sign of a media that can still get hustled in Three Card Monte by politicians and, in fact, loves it.

Can’t imagine why Blair and Bush might deserve their day in The Hague?

Well, of course not.

Thanks for reading. Please share if you enjoyed this edition…

… and consider upgrading to a paid subscription. The weekend newsletter with bonus material for paid subscribers will be out tomorrow.

Excellent - again. Few journalists come out well. Even fewer politicians. Except one: Charles Kennedy. His vile treatment by the Sun (Ed Rebekkah Brooks) for courageously and forcefully opposing the Iraq invasion would have done Der Stürmer proud.

Thank you, Mic. I eagerly await all your newsletters. You bring a real depth of research to everything you do.