The thrilling adventures of Pobert Reston! What Peston's ropey roman-à-clef tells us about modern journalism...

"I really enjoyed your novel ... way of writing a fucking awful story."

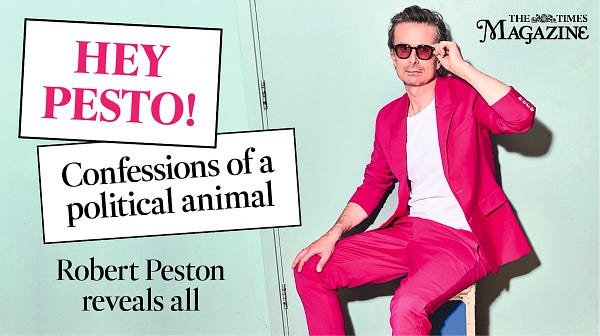

Robert Peston is on the front page of today’s Times Magazine dressed in a pink suit and resembling your dad cosplaying a chip-shop saveloy. Inside he appears in a similar eye-straining light blue suit as if auditioning for a show called Hawaii Five Hell No. This bout of sartorial shock and awe is not a mid-late life crisis, but part of the promotional push for Peston’s forthcoming debut novel.

Taking the entreaty to “write what you know” perhaps too literally, the protagonist and narrator of Peston’s novel The Whistleblower is a journalist called Gil Peck. Peck is the political editor of the fictional Financial Chronicle in the 90s (Peston was political editor of the Financial Times at the dawn of the Blair era) whose bosses mock his speaking style (“Thank God we put you in the papers and not on fucking television.”) and whose sister died in a cycling accident (Peston’s sister had a serious cycling accident but recovered).

That Peck is also extremely partial to cocaine gives Andrew Billen, the writer of the Times Magazine profile piece, the perfect in to ask Peston about his own relationship to drugs. After discussing teenage dabbling, Peston replies to Billen’s queries about his time at the Financial Times by saying:

To be clear, I’m not saying that I didn’t ever do drugs in my thirties or twenties. I did, periodically, but I was not somebody who had a habit like Gil or drank like him. I knew lots of people who only were able to function with cocaine and drink. That was absolutely not me.

That quote will be enough for The Daily Mail to spin up a double-page spread on “Peston’s drug shame”. But fact that Peston has Peck, his analogue, taking a line after “all of six pages”, according to Billen, suggests that he won’t be worried.

Far more cringeworthy than the drug confessions are the way Billen and Peston talk about journalism in the piece. Journalists, despite frequently ranking close to estate agents in lists of professions the public trust, love to think of themselves as cool, and that’s illustrated painfully by the following passage:

The drug of Gil and Peston’s choice is still just about legal: journalism, under William Randolph Hearst’s definition of it being something somebody doesn’t want printed. Peston has always derived “an incredibly childish pleasure” making people angry with what he has published. “In a not very attractive way, I quite enjoy exposing the frailties and the mistakes of the pompous and self-serving. Maybe it is in the public interest to do that, but I suspect it also [says] something about me. Maybe I had some chip on my shoulder.”

“[Journalism] is still just about legal…” writes an employee of The Times about the maverick, gonzo political editor of that radical Marxist outlet… ITV News, before indulging Peston’s fantasy that he is a scourge of the elite rather than a tremendously cushioned member of that club.

The son of economist and Labour government advisor Maurice Peston, who was made Baron Peston in 1987, Peston Junior did PPE at Balliol College, Oxford — whose alumni also includes Boris Johnson1 — before studying as a post-graduate at the Université libre de Bruxelles then becoming a stockbroker for Williams de Broë.

Peston got into journalism through Lucy Kellaway, an Oxford contemporary who also studied PPE, who tipped him off that her employer The Investors Chronicle was hiring. He went on to join The Independent when it launched in 1986, worked for the short-lived Sunday Correspondent (which only lasted 14 months), was City Editor of the Independent on Sunday, and worked for the Financial Times in various roles from 1991 to 2000.

As the Financial Times’ political editor — the period he has mined for his novel — he regularly wound up Alastair Campbell (who once responded to a query from him with the words: “Another question from the Peston school of smartarse journalism.”) but wasn’t quite the shooting star his later press suggested. In a grumpy dispatch for The Guardian in 2008, ‘Bill Blanko’ wrote:

In his days in the lobby, Pesto was a rather foppish character, so laid back he was almost horizontal. He replaced, as I recall, Philip Stephens, a very well-connected FT political editor and excellent columnist who was a hard act to follow. Unlike Phil, who always looked very intense… Pesto used to stroll up and down the press gallery corridor, known as the Burma Road, languidly and aimlessly, often looking as if he was deep in thought about anything other than what the hell he was going to write in his first edition splash.

In 2000, Peston jumped to become editorial director of the financial analysis startup Quest, while keeping one foot in journalism as a contributing editor to The Spectator (to which he still contributes) and as a weekly columnist for The Daily Telegraph (but he swiftly switched his allegiance to The Sunday Times).

He managed two years at Quest before joining The Sunday Telegraph as City Editor and Assistant Editor. The Times Magazine profile claims his itchy feet cost him “a £2 million digital windfall.” He was made Associate Editor of The Sunday Telegraph in 2005 but wouldn’t have that title for long.

In 2005, Peston was announced as Jeff Randall’s successor as BBC Business Editor. At the same time, his father Lord Peston was a member of the House of Lords BBC Charter Review Committee which is all very good and normal, and we shall say no more about it. Nudge, nudge, and indeed wink.

Peston’s scoops around the financial crisis led the Tories to suspect that he had a ‘mole’ inside Downing Street or the Treasury, and they demanded that the Serious Fraud Office investigate his September 2008 story about merger talks between HBOS and Lloyds TSB, after millions of HBOS shares were purchased in the minutes before the broadcast for a deflated price of 96p and then sold for 215p in the hour following it. No impropriety on Peston’s part was implied and nothing came of the ‘investigation’.

The following year Peston was involved in a public slanging match with James Murdoch at the dinner following the latter’s MacTaggart lecture. The Guardian reported at the time — neglecting to mention if Peston had whipped off his shirt and greased himself up with butter — that:

At an official dinner following the speech, Murdoch and Peston — who were sitting with the Newsnight presenter Kirsty Wark and the BBC chairman, Sir Michael Lyons — became involved in a discussion about banking deregulation which progressed to the flashpoint of whether or not the BBC was patrician, according to those who were there.

Murdoch apparently banged the table and shouted: "How dare you?" with Peston shouting back: "If you think you can get fucking angry, I can get fucking angry."

A source close to Murdoch, who oversees BSkyB as well as newspapers including the Sun and the Times, described the incident as a "vigorous exchange of views".

Who hasn’t encountered a scrap outside a local Wetherspoons triggered by a “vigorous exchange of views” about banking deregulation?

Peston became the BBC’s Economics Editor in 2013 before making the leap to ITV News in 2015 to succeed the royal bothering Tom Bradby as Political Editor. Billen assures readers of the Times profile that Peston made the move “lured less by the 30 per cent salary hike than the offer of his own programme” to which I reply: Chinny reckon.

Another of Billen’s doubtful assertions is that Peston’s novel is “brilliant” and that “The Whistleblower is politically insightful, scary, satirical, beautifully paced and has a great cast of characters…” It’s a bold claim when his article is book-ended by an extract from that novel.

Now, of course, it could be that the proof copy of the book that Billen has read is filled with remarkable passages that transcend the average airport thriller prose presented in the extract. But I suspect Billen, another Oxford man, is just giving the puffery promised in return for securing the interview.

Let’s take a look at some extracts from the extract. It opens like this:

Monday, March 3, 1997

All that interests me is the narrative, the story and who controls it. As a glory-seeking journalist, I sometimes reveal scandals. But more often I try to find out what the powerful in politics and business are planning, so that I can reveal it before they have the opportunity to impose their interpretation, their spin. In my more pretentious moments, I justify what I do as empowering “the people” to make up their own minds about how they are governed.Most of the time I am just having fun, pissing off ministers, chief executives, their minders, putting their secret schemes on the FC’s front page. If London is a collection of villages, I am the pedlar who wanders between the communities of politicians, financiers and businessmen, trading nuggets of information until I have enough to tell a tale that you’ll pay to read. Britain’s capital is vast and claustrophobically small. Everyone who matters knows everyone else who matters. My job is to eavesdrop, then share it with you.

While Peston has entirely swallowed the old canard to “write what you know” he seems to have failed to digest the other important lesson: “Show don’t tell.” So we have Pobert Reston… sorry, I mean Gil Peck just outright telling us he is “a glory-seeking journalist” and downloading his motivations in a big block of text.

Contrast that with how Evelyn Waugh reveals a newspaper editor’s mentality in one section of dialogue early in Scoop:

Mr Salter went to work at mid-day. He found the Managing Editor cast in gloom.

“It’s a terrible paper this morning,” he said. “We paid Professor Jellaby thirty guineas for the feature article and there’s not a word in it one can understand. Beaten by the Brute in every edition on the Zoo Mercy Slaying story. And look at the Sports Page.

Part of the difference is down to Waugh not being particularly bothered about showing journalists in a heroic light and, in fact, being entirely willing to show them for the egotistical, vainglorious bunch they tend to be.

What’s even more maddening about the extract from Peston’s novel, however, is that even after decades as a professional journalist he can’t make his main character — who is basically him — sound remotely like a real hack:

Tonight, I have an appointment that I hope will furnish me with a grade B scoop. Not something wholly unexpected, but in this time of general-election fever, a nugget that will sizzle at the top of the front page of the influential newspaper that pays me to make mischief…

Again, Peston doesn’t take the time to show us that the paper is influential but has to have the character tell us that. Peck, a 1990s newspaper journalist, talks like a Raymond Chandler character rewritten by an incompetently constructed machine learning algorithm.

This becomes even more painful when the Tony Blair stand-in enters the story:

I only half notice the rain because I am plotting how to land my mackerel; a story about the new darling of British politics, the prince of hope, Labour’s immaculately groomed and smooth young leader, Johnny Todd.

I know something is up, that Todd is planning one of his trademark policy coups, because my calls to his advisers are not being returned. My hunch is that they’ll want to announce whatever it is on Thursday morning, to set the agenda for one of the last prime minister’s questions before the looming election. Which means they’ll place it on Wednesday night in friendly newspapers – via the political hacks who take their dictation – to set the agenda for the Today programme the following morning. It will be a wheeze to woo the right-wing press, to reinforce Todd’s big claim that his party of the left won’t punish success and the successful. Or maybe Todd will wrap himself in the Union flag.

There’s more gall in that paragraph than a whole set of Asterix novels, given that Peston himself has been shown to repeat briefings word for word.

For example, Peston (along with the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg) had to apologise during the 2019 General Election after he parrotted an entirely false claim that a Labour activist had punched a Tory advisor. The apology only came once video evidence proved the line briefed out by, in Peston’s own words, “senior Tories” was horseshit.

And now we move on to some of that ‘insight’ that Billen promised, as Peston gives us a glimpse into how his mighty scoop-getting brain works:

My obsession is blowing up all politicians’ best-laid plans, regardless of party or ideological allegiance; to nick the information first, interpret it in my own way and blitz it on the FC’s front page. My reward?

The knowledge that when the FC first edition drops, my scoop will prompt night editors to ring up my rivals, pissed or asleep, to bollock them for missing the story. To earn this joyous schadenfreude, I have to deploy shameless skills of persuasion, to persuade one of Johnny Todd’s colleagues that I know more than I do and that I’m doing him a favour by listening to him. It’s a spiel, but it usually gets me there.

It’s a great indication of how Peston sees himself versus how the world at large sees him. In his mind and on the page, he’s a rough, tough political animal willing to piss off anyone to get the story. And in reality, he’s a foppish, fawning cartoon, who regularly publicly humiliates himself through the medium of Twitter.

Of course, newspaper journalists, columnists, and other preening media creatures will give Peston’s novel a good review. Firstly because there’s a high chance they went to university with him/might bump into him at a dinner or party, and secondly because they’re predisposed to like any story where a journalist is a hero.

Another quote beloved of a certain strain of ageing hacks is John Ford’s dictum that “when the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” In The Whistleblower, it seems that Peston is trying to write and print his own legend. But no matter how he powers up his Peck alter-ego, that pink suit is never going to work…

During an interview in the midst of the 2019 Tory Party leadership contest, Peston asked Johnson: “You would be the 20th Etonian to be Prime Minister. Now does that show this is a country fully functioning when it comes to social mobility or does it show that things don’t work out terribly fairly here?” Johnson’s reply shut him down quite effectively: “One Balliol man putting that question to another Balliol man.”

Classic Boris Johnson answer in the footnote - clever little journo-centric quip which technically avoids a relevant question, simultaneously confirms the dreadful truth, and entirely fails to offer a solution