So long, farewell, we Hadley knew you: The real function of columns vs. what columnists pretend they're doing...

Hadley Freeman's valedictory Guardian Weekend column repeated many of modern column writing's foundational myths.

One of the traditional ways for British columnists to start a piece is with a quote and, whenever possible, that quote should come from Orwell.1

The aim is to borrow a bit of credibility from poor dead Eric and give your potential chip paper argument a sense that, in fact, it belongs to the ages, the latest salvo in an argument that stretches back to Plato getting angry about “kids these days”.

The snappy line “Journalism is printing what someone else does not want published; everything else is public relations,” has become yoked to Orwell though he never said it. This polished version of the aphorism was, according to Quote Investigator, first attributed to Orwell in 1999 and has stuck since. In fact, it’s mainly a cut-and-shut of sentiments expressed by two press barons, one on either side of the Atlantic — Lord Northcliffe2 and William Randolph Hearst3.

Despite the fact that the quote belongs not to Orwell but to the founder of the Daily Mail — where publishing puff pieces and fact-free venom is central to the business model — and Hearst, whose papers pioneered scaremongering yellow journalism, it’s still quite useful. But that usefulness comes not from the sentiment of the line but from its ability to act as an early warning system. Anyone who quotes it seriously should be treated with suspicion.

It’s appropriate that journalists often find themselves alongside estate agents in lists of professions that the public trusts the least. Like estate agents, hacks are addicted to exaggeration and self-aggrandisement. There are few professions as in love with the myths around its work and worth than journalism.

Next week, The Guardian’s Saturday supplements (Review, The Guide and Weekend) are being rolled up into one new magazine, called — with the kind of creativity only a phalanx of branding consultants can deliver — Saturday.

This new dawn, which is most definitely not about cost savings, made the final editions of The Guide, Review and Weekend opportunities for a combination circle jerk and backslapping exercise, which now I picture it seems both socially and logistically unwise.

Weekend’s final issue also heralded the end of Hadley Freeman’s time as a columnist for the paper, a run that she detailed in her last contribution, a kind of meta-column:

For someone who never actually wanted to be a columnist, I have written a heck of a lot of columns. I’ve been a Weekend columnist for five and a half years, and before that, I was in the Guardian’s opinion section, and before that I was a columnist in the daily features section, G2, meaning I’ve foisted about 10 million of my random opinions on all of you. It has been a joy (for me, anyway), but now it is time to stop.

Humblebragging4 that you fell into column writing is an extremely on-brand thing for a columnist thing to do: “Yeah, I just tripped and landed in this job with a major national platform, relative security, and a good fee for disgorging the contents of my brain on a weekly basis.”

This performative disinterest in writing columns, which implies the 21 years of doing so was a series of embarrassing accidents, is mixed with a kind of Norma Desmondism (“I’m still big, it’s the opinions that have got smaller”).

In Freeman’s telling, no one wanted to be a columnist back in the year 2000, as if Richard Littlejohn hadn’t signed a £1 million deal in 1998 to write two columns a week for The Sun and Julie Burchill didn’t clean up in 2003 when The Times ditched her but was still obliged to honour her £300,000 three-year-contract.

Freeman has to sell the idea that column-writing was a scrappy corner of the media because her thesis is that “ever since the rise of blogging culture in the 2000s, when anyone with an Apple Powerbook (RIP) could knock out a column, pretty much every aspiring journalist…[wants] to be a columnist.” It’s a variation of the tediously common columnists’ theory: “It woz the Web what ruined it.”

Despite spending over 20 years in the lukewarm seat as a Guardian columnist, Freeman wants to kid the reader that she never really wanted it and it was just a well-paid inconvenience. So we’re told:

I can’t recall a single day — and there were thousands — that I spent sitting at my desk writing a column. I can, however, recall going to the Oscars to cover them or the weekend I spent with Judy Blume to interview her. Columns pump up the ego, but going out and finding stories is a lot more fun.

Perhaps Hadley Freeman truly has experienced an epiphany and decided that features and interviews are far more fun. But the notion that modern features and interview writing are about “banging on about fewer of [your] opinions and writing more about those of others” is dubious. Features and profiles are often a way for writers’ to push their opinions while pretending they’re unpicking someone else’s; it’s just marginally more subtle than a column.

Where the column gets really interesting — “interesting” is used here in the same way you might say, “That’s an interesting haircut…” — is when it makes the shift from the micro (Freeman’s personal experience of column writing) to the macro (“Wither columns…?”) and… uh… drags Jeremy Corbyn into it. She begins:

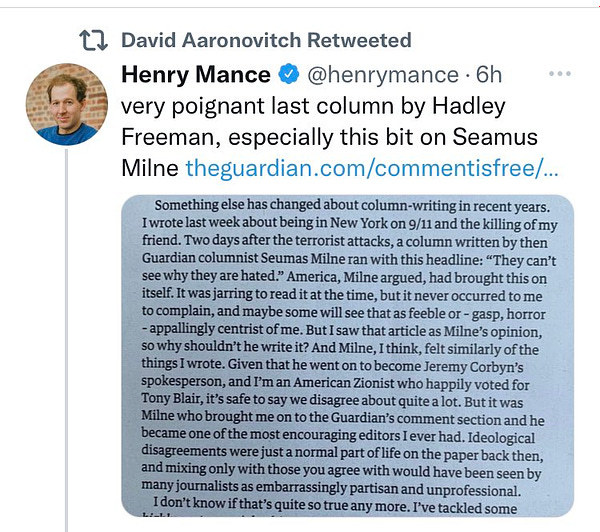

Something else has changed about column writing in recent years. I wrote last week about being in New York on 9/11 and the killing of my friend. Two days after the terrorist attacks, a column written by then Guardian columnist Seumas Milne ran with this headline: “They can’t see why they are hated.” America, Milne argued, had brought this on itself. It was jarring to read it at the time, but it never occurred to me to complain, and maybe some will see that as feeble or – gasp, horror – appallingly centrist of me.

But I saw that article as Milne’s opinion, so why shouldn’t he write it? And Milne, I think, felt similarly of the things I wrote. Given that he went on to become Jeremy Corbyn’s spokesman, and I’m an American Zionist who happily voted for Tony Blair, it’s safe to say we disagree about quite a lot. But it was Milne who brought me on to the Guardian’s comment section and he became one of the most encouraging editors I ever had. Ideological disagreements were just a normal part of life on the paper back then, and mixing only with those you agree with would have been seen by many journalists as embarrassingly partisan and unprofessional.

The idea that no one ‘mixes’ with anyone they disagree with — even if that disagreement is as real as professional wrestling grudges — is another of the useful myths of modern comment journalism. “We are so polarised!” columnists scream, before attending dinner parties where Telegraph hacks and Guardian lifers rub shoulders happily, laughing it up at literary festivals, and chumming around in green rooms after TV recordings.

Milne is presented as some AK-toting, beret-wearing Marxist, foaming at the mouth as he plans his shadowy schemes, but he’s establishment born — the Winchester College and Balliol College, Oxford-educated son of a Winchester College and New College, Oxford-educated former Director-General of the BBC. Before he was hired by Jeremy Corbyn as the Labour Party’s Executive Director of Strategy and Communication, he was seen as an eccentric whose positions could be used by The Guardian to claim it truly was “a broad church".

Having once again pretended that the media of 2021 is a uniquely hostile time for national newspaper columnists compared to the collegiate joy of the year 2000, Freeman continues:

… where once people could argue with one another and then go out for a drink, now it feels as if people just argue. A difference of opinion becomes a seismic breaking of alliances and certain subjects are verboten in social situations.

I could blame Brexit for this – a difference of opinion that pretty much broke this country – but I noticed it before. In May 2016, I watched a documentary about Corbyn, made by Vice, and in one scene Corbyn gets very angry about a column Freedland wrote in the Guardian, about antisemitism in the Labour party. He makes a call — to Milne, as chance would have it — and the two of them discuss Freedland: “He’s not a good guy at all. He seems kind of obsessed with me,” Corbyn rages.

I’ve watched that Vice documentary about Corbyn and his office a couple of times since it was released but I had to go back and watch the scene Freeman wrote about to make sure I hadn’t misremembered it.

There are many things you can say about Jeremy Corbyn — and people usually do — but the idea of him ‘raging’ is fanciful. His ways of expressing annoyance, another aspect of his personality constantly dissected by the British media, are at best irritation and at worst peevishness.

In the scene where he is shown on the phone to Milne — up there with the “Seamus, I'm not sure this is a great idea either…” clip in the list of times team Corbyn allowed cameras backstage — Corbyn doesn’t rage. He’s annoyed as any human being might be about what they perceive to be repeated and unfair attacks on their character.

What Freeman — an opinion columnist of two decades standing — is objecting to in Corbyn’s words (“He’s not a good guy at all…”) is someone expressing their opinion of someone else. He’s not ‘raging’ — picture Corbyn transforming into a red Hulk, homemade jam flying everywhere — but he’s annoyed and from that Freeman extrapolates a ‘lesson’ about modern public discourse:

… it felt like a turning point, a shift from when readers merely disagreed with a column to disagreeing and therefore assuming the columnist is A Bad Person. All newspaper columnists will have experienced degrees of that shift over the past five years, and this is not – as some have said – about holding them accountable for their opinions; it’s a refusal to accept that not everyone sees things the same way. Yet this, surely, is what columns are all about: revealing the variety of perspectives. So it’s ironic that at a time when column-writing has never been more desirable to so many, there is such an expectation of conformity of opinion.

The irony of Freeman talking about “a refusal to accept that not everyone sees things the same way” after she has just turned a couple of opinionated lines from Corbyn into the quote carved onto the tombstone of ‘reasonable’ debate is acute. Boil down her sentiments and you’re left with another common columnist demand, memorably summed up by Trashfuture’s Alice Caldwell-Kelly as “it should be illegal to @ me”.

What has changed since Freeman began writing columns in 2000 is that it’s far easier for readers to tell a columnist that they’re wrong, loudly and at length. In the past, columnists could write with impunity because the worst they’d get was a pile of post to the letters page that they never see or a counter-blast from a rival columnist, resulting in a war of words — sometimes by fax — that would simply increase both writers’ profiles.

The notion that the issue with columnists is that people outside of journalism demand conformity of opinion is absolute mirror world logic. There is no trans person with a regular national newspaper column articulating that view. Where are all the black columnists with regular access to a national platform? Most columnists in British national newspapers are over-40, white, and either based in or linked to London.

The ease with which a writer can slip from The Guardian to The Daily Telegraph or conversely from The Daily Mail or Daily Telegraph to The New Statesman is not an example of their flexibility but of the homogenous quality of British media.

Columns aren’t there, as Freeman, suggests to “reveal a variety of perspectives”. Any columnist who regularly offered perspectives that were counter to the accepted lines of the British media — on houses, landlords, the market, politics, royalty, sexuality, class — would not have that job for long.

When the much-missed Dawn Foster wrote a column that diverged from the acceptable lines, she was pushed out. Dawn recounted herself the incident on an edition of the Left/Over podcast (‘Guardians of the Galaxy Brain’):

When I did put forward the Tom Watson article I was very surprised that they did actually say yes… it was edited, all fine. And then I just got an email that said, ‘Just so you know, won’t be renewing your contract but you’re perfectly welcome to send in any ideas you have in the future and we’ll take a look at them’. I was like, ‘Fine by me, perfectly happy not to have to constantly send in articles every week and have them constantly turned down because you want to give the ideas to somebody more right-wing.’

Later, I was told that somebody else had spoken to Tom and he was unhappy. A different journalist had sent Tom a text message that he had become annoyed at and he had complained to the editor about that text message and also my article.

The rallying cry of the columnist is “no one tells me what to write” but the point is that no one has to. Every columnist knows that they are subject to the whims of the editor and, ultimately, the peccadillos of the proprietor. If they fall foul of either, they’re gone. A columnist who sticks around for decades is a columnist who knows how to endlessly compromise.

Columnists are encouraged to think of themselves as mavericks because they often say things that upset people but they don’t say things that would upset their proprietors or the kind of people they are likely to bump into at a book launch or a dinner party.

To ensure that this edition of the newsletter ends in a manner understandable to the average British columnist, let me dig out some Orwell. In Animal Farm, he writes about the farm after the pigs have turned it into a dictatorship:

The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.

Pick up the papers today and look from Sunday Times to Observer, and from Observer to Sunday Times, and from Sunday Times to Observer again; already it is impossible to say which is which.

Rod Liddle offers a clunky example of this technique in today’s Sunday Times in the opening paragraph of his column: “George Orwell once said: ‘When I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict with his natural enemy, the policeman, I do not have to ask myself which side I am on.’ I can remember thinking, when I read those words years ago: you sure about that, George?”

In a chapter included in Journalism as a Profession (1903), Northcliffe (then just plain old Alfred Harmsworth) wrote: “It is part of the business of a newspaper to get news and to print it; it is part of the business of a politician to prevent certain news being printed. For this reason, the politician often takes a newspaper into his confidence for the mere purpose of preventing the publication of the news he deems objectionable to his interests.”

In 1930, the syndicated columnist Walter Witchell quoted Hearst’s version of the saying in a column. In the following quote, ‘good news’ means ‘genuine news’ rather than something that would make you smile: “Hearst chirped a mouthful when he recently said that, ‘When a man wants to keep anything out of the paper it is good news! When he wants you to print it—it is propaganda or advertising!’”

Given the sheer amount of things that Freeman has written about for The Guardian, it’s no surprise to find that she wrote about the late Harris Wittels, coiner of the term “humblebrag”.