School of hard Knox: For the British press no one is ever truly innocent whatever courts say...

Innocence is no defence against the Sauron eye of the newspapers.

You don’t know Colin Stagg. Neither do I. There’s a good chance that his name is one of those ones that sort of nudges a fragment of memory at the back of your mind but doesn’t quite knock it into the front of your consciousness.

Stagg sits in a particular category of person who has made the news: Those who are never allowed the peace of their innocence.

He was once splashed all over the front pages, his every movement a prompt for another story drenched in insinuation and innuendo. Now he’s more of a pub quiz tiebreaker: “Who was falsely charged with the murder of Rachel Nickell in 1992 and acquitted at trial in 1994?”

But Stagg’s welcome obscurity has been broken by Channel 4’s forthcoming four-part drama Deceit, which focuses on a sting operation conducted by the police in 1993 that attempted to force Stagg into admitting to the crime; an attractive female officer was assigned to pretend to be both beguiled by him and turned on by the idea of violence.

Attempting to wring a confession out of Stagg, the police officer told him he could only win her heart if he admitted to a shared love for satanic ritual and child murder. A tape released by the police featured the undercover officer telling him that she enjoyed hurting people, intimidated and upset he replied:

Please explain, as I live a quiet life. If I have disappointed you, please don’t dump me. Nothing like this has happened to me before.

The officer responded by telling him:

If only you had done the Wimbledon Common murder, if only you had killed her, it would be all right.

Stagg, who simply didn’t want to be alone, replied:

I’m terribly sorry, but I haven’t.

The police didn’t believe him and neither did the newspapers who treated his acquittal as proof of a soft liberal judiciary rather than a decision made by someone in command of the facts who saw there was no evidence to implicate Stagg in the killing. Sir Harry Ognall, the trial judge, dismissed the material gathered during the honey trap operation as inadmissible in a pre-trial hearing because it was the biggest set-up this side of Wiley Coyote sticking a fake tunnel entrance on a rock wall.

Ognall, who prosecuted Peter Sutcliffe as a QC, was vilified in the press for his decision. When he died earlier this year, The Times still referred to his decision in the Stagg case as a “controversial acquittal” in its obituary, though it did note that “he was later vindicated”.

In 2008, after Stagg was awarded £706,000 compensation from the Metropolitan Police, Ognall wrote (also in The Times) that he hoped he could be:

… confident that the vendetta pursued against me by certain newspapers in the aftermath of the trial in 1994 is now put to rest.

In the piece, published the day after Robert Napper — Rachel Nickell’s real killer entered a guilty plea — Ognall reflected on the events of 14 years earlier:

It is a graphic measure of the frailty of the prosecution case that, bereft of the foothold offered to them by that rotten plank, they elected to drop their case, and Mr Stagg was acquitted.

Since then a campaign of innuendo has been mounted in sections of the press that has repeatedly invited the public to conclude that Mr Stagg had literally “got away with murder”. The truth, of course, was that he had not got away with anything. He had been singled out because he was a soft target. His appearance, his lifestyle and the libidinous exchanges with the policewoman painted him in singularly unattractive colours.

… There will no doubt be suggestions that there are obvious lessons to be learned from this 14-year saga. I am not so sure. Media hysteria, an embattled police force and the duty of a criminal trial judge to ensure inherent fairness of the process are not novel dimensions in the history.

He was right. Two years later, Christopher Jefferies — another innocent man — was presented as a monster by the British press after he was wrongly implicated in the murder of Joanna Yeates. Speaking at the Benn Debate on the future of the media in 2012, Jeffries said the story of Yeates’ murder just before Christmas 2010 and his subsequent arrest was “a ready-made Midsomer Murders script set in an apparently respectable, leafy suburb”; in other words, a gift to the papers.

Jeffries with his shock of white hair, polo neck, and old coat was easy for the newspapers to caricature. They claimed he was smirking when he was pictured outside his home and The Sun and Times alike dubbed him “The Strange Mr Jefferies”. The Daily Mail splash screamed “Murder police quiz ‘nutty professor’ with a blue rinse” while The Daily Mirror claimed, “Jo suspect is Peeping Tom”.

Adjectives including “weird”, “lewd”, “creepy”, “angry”, “odd”, “eccentric” and “loner” were sprinkled through the coverage and resolutely normal aspects of the former English teacher’s career were twisted out of all recognition in the fairground mirror of tabloid insinuation.

The fact Jefferies liked Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol was recast as a claim that “Chris Jefferies’ favourite poem was about killing a wife.” And teaching pupils about the Holocaust and Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone (“a Victorian murder novel” in tabloid parlance) ‘proved’ he was “obsessed with death”.

In a 2011 interview with The Guardian, Jefferies observed:

I don't suppose whoever wrote that has ever read Wilkie Collins. They just thought, 'Oh, we need evidence of decadence and depravity... That will do!'

Meanwhile, headlines presented questions that solidly proved Betteridge’s Law1. “Could this man hold the key to Joanna’s death?” No. “Was Jo’s body hidden next to her flat?” (accompanied with a picture of Jefferies). Also no.

The media vilification of Jefferies gave the real killer, Vincent Tabak, the chance to attempt to shift the blame. After seeing TV reports on Jefferies’ arrest while visiting relatives in the Netherlands over New Year 2010/11, he contacted Avon and Somerset police to claim that Jefferies had been using his car. A CID officer, DC Karen Thomas, was sent to Amsterdam to speak to him.

They met at Schiphol Airport on December 31 2010 and Tabak spun his tale. But Thomas became suspicious when Tabak asked about the police’s forensic work and said things that contradicted his previous statement. Tabak was arrested on January 20 2011 but details of his identity were not released because of the way the media had responded to Jefferies’ earlier arrest. He was found guilty of Joanna Yeates’ murder by a majority verdict on October 28 2011, and jailed for life with a minimum term of 20 years.

Jefferies received damages from The Sun, The Mirror, The Sunday Mirror, The Daily Mail, The Daily Record, The Daily Express, The Daily Star and The Scotsman. The Mirror and The Sun were also fined for contempt of court in a case brought by the Attorney General which resulted in fines of £50,000 and £18,000 respectively; little more than paper cuts.

Avon and Somerset Police also made a £50,000 payout and apology to Jefferies for loss of income and property damage that it caused during its investigations.

After appearing at the Leveson Inquiry, Jefferies has become a campaigner for privacy and press ethics. His story was told in an ITV drama The Lost Honour of Christopher Jefferies (2014). But Google ‘Christopher Jefferies” now and you’ll still be prompted by Google with the question: “Was Christopher Jefferies a peeping tom?” The British press’ smears are hard to wash away.

And while most of the coverage published by the British newspapers during the hysterical pursuit of Jefferies has been memory holed, The Times story ‘Strange Mr Jefferies’ knew boyfriend was away remains online. The piece is like a time capsule of insinuations. No update or clarification has been added to it in the 11 years since it was published. Fiona Hamilton, one of three journalists bylined on the story, is still The Times’ Crime & Security Editor.

While Christopher Jefferies made the decision to become a campaigner, Colin Stagg did not. In 2008, 14 years after his wrongful arrest and trial, he received compensation of around £750,000 from the Home Office. He used the money to do things he hadn’t been able to when he was younger because of the spectre of the false allegations hanging over him.

Chased down by The Sun in 2018 for a story headlined Stag Blows Compo, he explained, though he absolutely should not have had to, that:

I spent like there was no tomorrow. I bought vehicles for me and my girlfriend. I treated myself to clothes, jewellery and expensive guitars. After decades without a holiday, we took three or four a year. I was making up for lost time doing things I should’ve done in my youth if I hadn’t been blighted by Rachel’s murder. I got a passport for the first time and fulfilled a lifelong ambition to visit the Pyramids.

See, I don’t think that’s “blowing” the money. I think it’s spending it on things that made life a little better for him and his family. But The Sun made sure to note Stagg was once “Britain’s most hated man” and use ambiguous picture captions like “he was jailed for the stabbing - but was later freed” to encourage readers to feel angry that he had been ‘given’ so much money.

Earlier this year, following the announcement of the Channel 4 drama, The Daily Mail papped Stagg on his way to work at Tesco, headlining its entirely unjustified intrusion into his life with the line Colin Stagg is working at Tesco after blowing £700,000 payout for being wrongly accused by police in notorious Rachel Nickell honeytrap murder probe. The story began:

It is nearly 30 years since he was at the centre of one of Scotland Yard’s most notorious operations, yet strangers still recognise him – although usually they can’t quite recall why.

Colin Stagg is now 57, greying and portlier than when he hit the headlines in the early 1990s, but there is no mistaking his features as he heads to his local Tesco Express for his checkout shift.

Like The Sun, The Daily Mail aimed to rile up its readers about Stagg ‘blowing’ money to which he was entitled and which still doesn’t come close to recognising the suffering he endured. It has been nearly 30 years since he was wrongly targeted by Scotland Yard and here’s The Daily Mail stalking him on his way to work, sneering about the fact that he works on a supermarket checkout and as a warehouseman.

The paper spoke to his colleagues and wrote about his family life and home. And yet it affects surprise that “strangers still recognise him”. Perhaps if the papers didn’t splash pictures of him every few years, crowing about how he “blew his compo”, it would be a lot easier to live the quiet life he clearly wants to have.

Once you’ve been part of a major news story, newspapers, particularly The Daily Mail, believe you are fair game forever. Recently it used a new documentary about Amy Winehouse’s death as an excuse to pap her last boyfriend Reg Traviss, his wife, Zita Teby, and their child as they walked in the street. The additional hook was that Teby, appeared in one of his films with Meghan Markle.

While it’s reported that Stagg spoke to the makers of Deceit and helped with research for the drama, not everyone who becomes a character in the news gets that courtesy. Amanda Knox, who faced eight years of trials and four years of imprisonment for the 2007 murder of Meredith Kercher before being definitively acquitted by the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation in 2015, wrote this week about her story being taken by the makers of the new film Stillwater.

In a piece headlined Who Owns My Name? Knox writes:

This new film by director Tom McCarthy, starring Matt Damon, is “loosely based” or “directly inspired by” the “Amanda Knox saga,” as Vanity Fair put it in a for-profit article promoting a for-profit film, neither of which I am affiliated with. I want to pause right here on that phrase: “the Amanda Knox saga.”

What does that refer to? Does it refer to anything I did? No. It refers to the events that resulted from the murder of Meredith Kercher by a burglar named Rudy Guede. It refers to the shoddy police work, prosecutorial tunnel vision, and refusal to admit their mistakes that led the Italian authorities to wrongfully convict me, twice.

In its September 2015 report on the case, the Italian Supreme Court spoke of “glaring errors”, “investigative amnesia” and “guilty omissions” on the part of the police. It decried “sensational failures” in the investigation and not only ruled that there were errors in earlier court cases and a lack of evidence but that Knox was innocent of involvement in the murder.

It’s worth noting however that Knox was not acquitted of the crime of calunnia (calumny/defamation) against Patrick Lumumba, a Congolese bar owner whom she had falsely accused of committing the murder. Her three-year sentence for that offence was deemed served during her time in prison.

But the media continues to leave Meredith Kercher’s name out of headlines and focuses on Knox rather than the convicted killer Rudy Guede, not because she falsely accused Lumumba but because the idea of a “murderous sex-crazed exchange student” is just too compelling to drop.

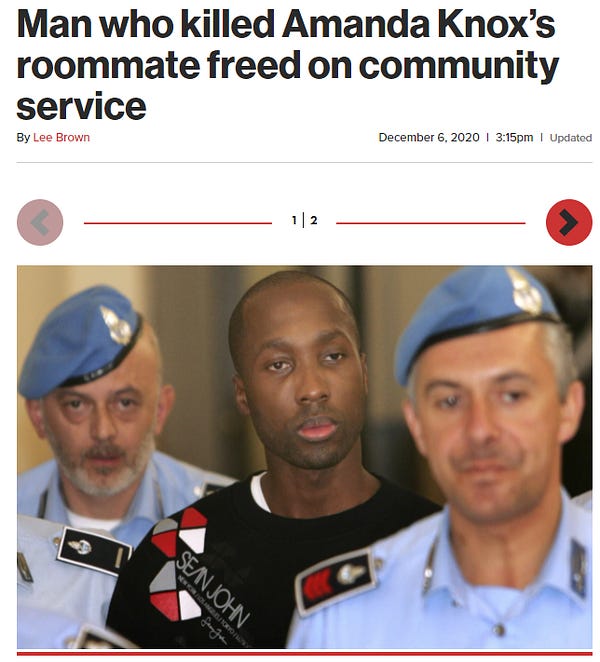

As Knox noted in her article, the New York Post’s headline in December 2020 about Guede’s release for community service read:

Man who killed Amanda Knox’s roommate freed on community service.

Kercher was not given the dignity of her name in death and Knox was there in the headline as SEO-bait. The first paragraph of the story was an insinuation:

The only person serving time for the murder of Amanda Knox’s roommate Meredith Kercher has been released from prison to finish his sentence with community service, according to reports.

To say “the only person serving time…” suggests a belief that there should be others behind bars too.

In today’s Sunday Times, Camilla Long — one of British media’s many Camillas — uses an old columnist’s trick (the cut and shut) to weld together the minor story of Flora Gill writing a grim (and now deleted) tweet proposing “entry-level porn” for children with the major and ongoing story of Amanda Knox being tied to a murder she did not commit. Long writes:

I’m interested in Gill because there was another posh fey white woman2 begging us to “just let it die”, as Gill put it, on Friday. Her case is more serious. Amanda Knox describes herself as an “exonoree” in her Twitter bio, but her extraordinary 44-point thread — an exorcism, really — suggested she was the only person in the world who really viewed herself as innocent.

A new film, Stillwater, in which Matt Damon plays the father of a girl who’s in prison for a murder she didn’t commit, is “directly inspired” by “the Amanda Knox saga”, she said. It turns out (spoiler) the girl “asked the killer to help her get rid of her roommate”, she wrote. “How do you think that impacts my reputation?”

Reading Knox’s tweets is often tiresome: they’re filled with victimhood and self pity. She draws poor conclusions, such as likening herself to Monica Lewinsky. She doesn’t like people saying it’s “the sordid Amanda Knox saga’” as sordid means “morally vile” and it’s “not a great adjective to have placed next to your name”. But you can’t control what people call things, or your “story”. And who on earth complains about something this petty, when half the globe still thinks you’re the woman who killed your friend in a satanic sex ritual?

It would be too much to ask for empathy from Long, she’s not paid for that, but the cheap shots in that last paragraph are shocking even from one of Britain’s most consistently unpleasant bylined trolls.

Perhaps Knox’s tweets are “filled with victimhood” because columnists like Long are still writing sentences like “half the globe still thinks you’re the woman who killed your friend in a satanic sex ritual” about her. After years wrongfully held in prison and protracted trials, I too might feel a smidge of victimhood.

The column gets much worse. Long continues:

Given she is innocent, as an Italian court finally concluded six years ago, why is it that people still won’t believe that she is? She can repeat, again and again, that she has been found not guilty, but it is almost as if none of us want to hear it. None of what she has experienced can apparently be “deleted” and forgotten, as Gill suggested her own tweet should be, because the story of Knox as a sex killer is too compelling. And I find that kind of awful.

… Just as it was easy for the victims of Jack the Ripper to be painted as prostitutes, it was easy for the prosecution to cast this young American student as a sex-obsessed killer. If she is guilty of anything, it is helping them. You looked at her snogging her boyfriend just metres from the house where Kercher was killed, and think, “How can you be that stupid? Where were your people?” But she didn’t even know at that point that Kercher had been murdered.

“If she is guilty of anything…” Despite noting correctly that the Italian police did things like lying to Knox that she had HIV to prompt her into writing a list of former lovers which they then leaked to the press, Long still finds a way to blame Knox as if a 20-year-old should be expected to react sensibly and rationally to being at the heart of a terrifying storm.

In her conclusion, Long opts for another columnist’s classic — having it both ways — writing that:

I find it difficult to sympathise with Knox when she talks like a greedy lawyer. But if we defend the nice, compliant women, shouldn’t we defend the complicated, difficult, unlikeable ones as well?

It is Long and other people in the media who have sold us the story that Knox is “complicated, difficult [and] unlikeable”. It is Long who did just that in the very column I’m looking at now but still she also claims to “defend” Knox as the insinuations and insults pile up around her.

There’s a voice from the Joanna Yeates story that is often left out of retellings. Her boyfriend, Greg Reardon, issued a statement in January 2011 that was a celebration of his partner (“Jo was a beautiful woman, beautiful in mind, body and soul…) but also a stinging criticism of the media coverage of her death:

Jo's life was cut short tragically but the finger-pointing and character assassination by social and news media of as yet innocent men has been shameful. It has made me lose a lot of faith in the morality of the British press and those that spend their time fixed to the internet in this modern age.

I hope in the future they will show a more sensitive and impartial view to those involved in such heart-breaking events and especially in the lead-up to potentially high-profile court cases.

Sadly, 10 years on, Reardon’s hopes remain just that and the reality of the British media is still one where innocence is decided not in the courts but in the keystrokes of hacks and the judgements of their editors.

“Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no.”

Camilla Long calling someone else a “posh fey white woman” is very ‘Spiderman pointing at Spiderman’ meme.