Paper Stings

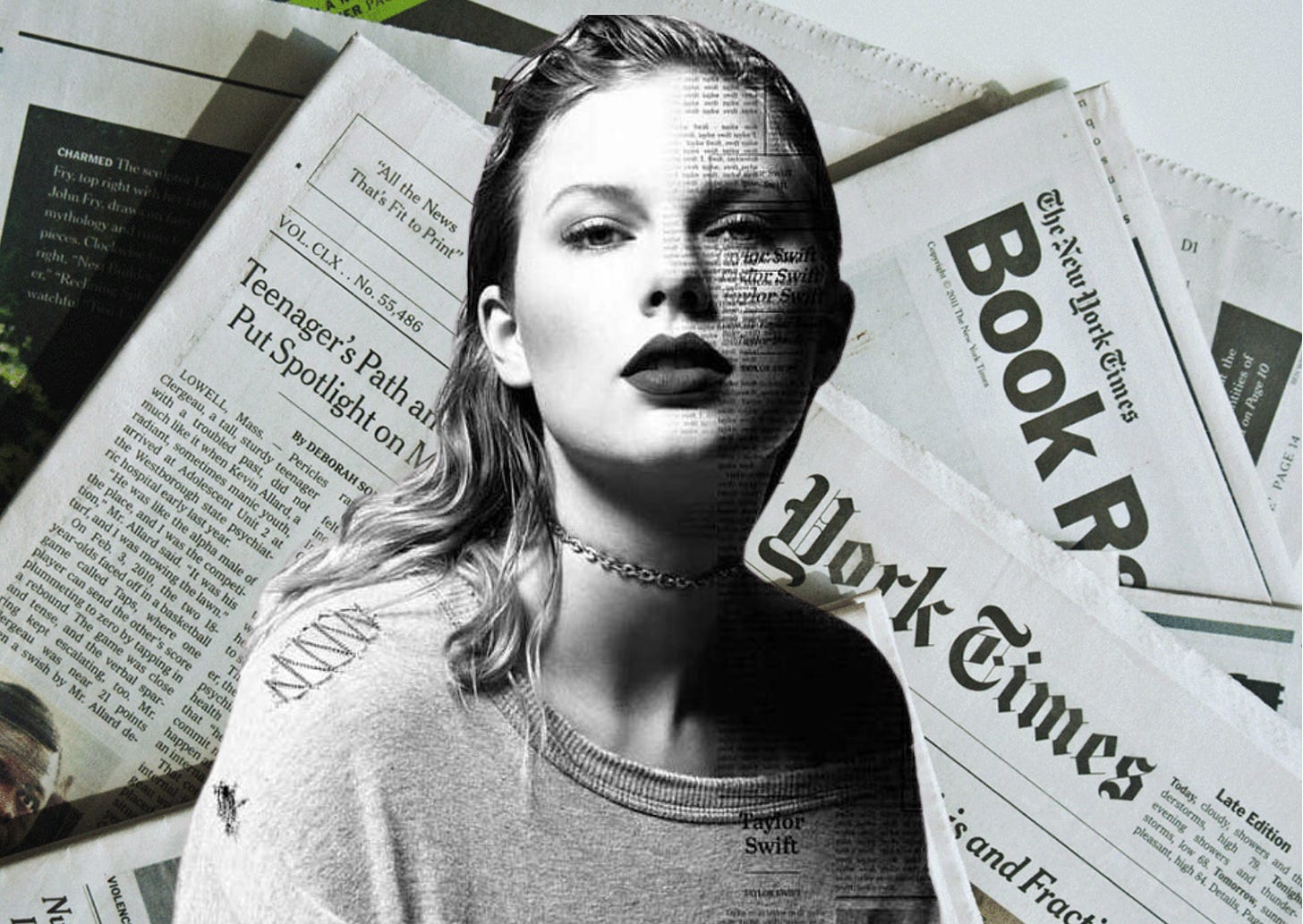

The New York Times op-ed speculating about Taylor Swift's sexuality shows how media ethics can be a blank space.

Welcome to the first newsletter edition of 2024. I’m writing my first book over the next few months but there will still be two free editions of the newsletter per week plus the Sunday recommendations email with bonus content for paid subscribers. Consider upgrading if you want to get that extra stuff and help keep this sustainable as a newsletter. I’ll also have news on moving newsletter platforms soon.

Previously:

The 23 worst columns of 2023, part 3: Festive Shits from the Fetid Five

In 1992, The Face published a feature on the ‘outing’ of gay celebrities. While the piece noted that people — both journalists and activists — plagued Jason Donovan seeking to expose him as gay, even though there was no evidence that he was, it was also illustrated with a poster made by outing campaigners featuring the actor/singer wearing a t-shirt that read: Queer as Fuck.

Donovan sued and ‘won’. It was one of British legal history’s most pyrrhic victories; he claimed he had been objecting to being painted as a liar rather than having a problem with people thinking he was gay but his barrister had called it “a poisonous slur” and he was widely seen as homophobic. Other celebrities rallied around The Face, which set up the Lemon Aid Fund — so named because it had alleged the singer bleached his hair with lemon juice — to help pay the £150,000 costs and £200,000 damages.

While Donovan declined to claim his damages — saying he felt a sense of “righteous guilt” — he alienated a huge part of his fanbase and left himself out in the cold for years. His decision to sue didn’t stop the spread of the Queer As Fuck image either; Chumbawamba printed hundreds of t-shirts bearing the image and gave them away with their single ‘Behave’.

I was prompted to recall this 32-year-old curio of media gossip and legal history by a New York Times op-ed — curiously tagged as a ‘guest essay’ —in which one of its opinion editors Anna Marks speculates wildly about Taylor Swift’s sexuality.

Headlined Look What We Made Taylor Swift Do, the 5,000-word piece is made up of a long list of LGBTQ+ references in Swift's songs that are either overt or which Marks perceives to be present in the lyrics. Her thesis is that Swift has been trying to send a signal about her sexuality for years. She writes:

In isolation, a single dropped hairpin is perhaps meaningless or accidental, but considered together, they’re the unfurling of a ballerina bun after a long performance. Those dropped hairpins began to appear in Ms. Swift’s artistry long before queer identity was undeniably marketable to mainstream America. They suggest to queer people that she is one of us.This kind of theorising about stars and their sexualities is pretty common in the heavy-handed Tumblr-driven world of fandoms. The idea that Swift might be secretly gay or bisexual has been around for years; it even, inevitably, has a portmanteau name — Gaylor — but there should be a difference between the hot and heavy speculation of fan accounts and blogs, and the comment pages of an international newspaper. There increasingly isn’t but there should be.

It’s not that the notion that Swift could be gay or bisexual is in and of itself offensive or “a poisonous slur” as Donovan’s barrister claimed all those years ago but that her right to define herself and her sexuality is not erased by her celebrity. Marks’ hijacking is only made grimmer by her use of another singer’s personal life (and trauma) for a rhetorical flourish. Her piece begins:

In 2006, the year Taylor Swift released her first single, a closeted country singer named Chely Wright, then 35, held a 9-millimeter pistol to her mouth. Queer identity was still taboo enough in mainstream America that speaking about her love for another woman would have spelled the end of a country music career. But in suppressing her identity, Ms. Wright had risked her life.Wright wrote over the weekend:

I was mentioned in the piece, so I’ll weigh in. I think it was awful of The New York Times to publish. [It was also] triggering for me to read — not because the writer mentioned my nearly ending my life — but seeing a public person’s sexuality being discussed is upsetting. The point at which Marks’ piece takes flight into indefensible fan fiction comes after a discussion of a video of Wright recorded during a bookstore even promoting her 2010 memoir Like Me:

[Wright] likens closeted stardom to a blender, an “insane” and “inhumane” heteronormative machine in which queer artists are chewed to bits. “It’s going to keep going,” Ms. Wright says, “until someone who has something to lose stands up and just says, ‘I’m gay.’ Somebody big.” She continues: “We need our heroes.”

What if someone had already tried, at least once, to change the culture by becoming such a hero? What if, because our culture had yet to come to terms with homophobia, it wasn’t ready for her?

What if that hero’s name was Taylor Alison Swift?That “what if?” is where the essay swerves right off the road. Is it possible to talk about queer imagery in Swift’s songs and her relationship with her LGBTQ+ fans? Or to explore the question of homophobia in country music and America more widely stopping artists from showing their authentic selves? Or even look at whether Swift indulges in ‘queer baiting’? Yes. Of course.

The problem comes when Marks decides to turn Swift into “the hero” she’s seeking; not a human being who has been pretty clear about her sexuality but a rhetorical device represented more in lyrical allusions — both real and imagined. In 2019, Swift told Vogue that she became more vocal in her support for LGBTQ+ people because:

I didn’t realise until recently that I could advocate for a community that I’m not a part of. It’s hard to know how to do that without being so fearful of making a mistake that you just freeze. Because my mistakes are very loud. When I make a mistake, it echoes through the canyons of the world. It’s clickbait, and it’s a part of my life story, and it’s a part of my career arc. Marks’ essay is effectively a piece of long, ponderous, and pretentious clickbait, from that loaded headline onwards. She quotes that same Vogue interview but spins the “a community that I’m not part of” line to serve her thesis:

That statement suggests that Ms. Swift did not, in early June [2019], consider herself part of the L.G.B.T.Q. community; it does not illuminate whether that is because she was a straight, cis ally or because she was stuck in the shadowy, solitary recesses of the closet.Settling into her theory, Marks reaches back to 2019, Swift’s ‘Lover’ era — whose “rainbows, butterflies and pastel shades of blue, purple and pink” she says subtly evoke the bisexual pride flag — and writes:

Ms. Swift performed “Shake It Off” as a surprise for patrons at the Stonewall Inn. Rumours — that were, perhaps, little more than fantasies — swirled in the queerer corners of her fandom, stoked by a suggestive post by the fashion designer Christian Siriano. Would Ms. Swift attend New York City’s WorldPride march on June 30? Would she wear a dress spun from a rainbow? Would she give a speech? If she did, what would she declare about herself?The aside — “that were, perhaps, little more than fantasies” — should have been the point at which Marks or her editors stopped and considered what they were pushing into print. But they didn’t. Instead, Marks merely doubles down on her fantasising:

When looking back on the artifacts of the months before that album’s release, any close reader of Ms. Swift has a choice. We can consider the album’s aesthetics and activism as performative allyship, as they were largely considered to be at the time. Or we can ask a question, knowing full well that we may never learn the answer: What if the “Lover Era” was merely Ms. Swift’s attempt to douse her work — and herself — in rainbows, as so many baby queers feel compelled to do as they come out to the world?The question is bad but where Marks is asking it is worse. She is not a fan theorising to a small group of fellow Swifties but a New York Times opinion editor making use of that paper as a megaphone. It’s an unethical and unconscionable thing for someone employed as a professional journalist to do. And it’s not the first time she’s done it.

In August 2022, Marks wrote another ‘guest essay’ for The New York Times opinion section about Harry Styles, asking if “one of the most famous people in the world could be trapped in the same closet as you or me?” The paper’s letters page printed a sharp response from Kevin Ivers of Washington:

I am a 54-year-old queer man who has been fully out of the closet since I was 18. The symbols of queer identity are not ‘ours’ like a trademark litigation case. Queerness is not a sorority with strict hazing rituals to earn admission. And the price of Harry Styles’s concerts does not entitle others to make any demands on his private life, his truth or his journey. They can ignore him, not buy his concert ticket, critique his art, his costumes, his hair, or whatever irks them about pop music. They have no right to appropriate his or any other human being’s truth. That’s the whole point of queerness. I don’t get the impression that Marks read that particular correspondence.

In writing about ‘dropped hairpins’, Marks is referring to vintage gay slang for revealing your sexual preferences through hints — “keep your hairpins up” was an instruction to put on a front around people who might threaten you and the Stone Wall riots were “the hairpin drop heard around the world,” in the words of the activist Dick Leitsch. Talking about ‘dropped hairpins’ in Swift’s work is a long-time hobby of the Gaylor fandom. But Frankie de la Cretaz, writing for Xtra*, says: “Hairpin drops do not exist for straight people,” and continues:

… if you think that rumoured queerness is something that a celebrity needs to be defended against, if you think that suspecting someone might be gay is slandering them in some way, I’m going to have to ask you to unpack that homophobia.

When you say that queers are doing harm by reading queerness into someone’s art, what you’re actually saying is that being seen as gay is a negative thing.I don’t think there is a problem with reading queerness into Swift’s work. But the key is to focus on the last two words of the previous sentence — the work. If the framing of Marks’ essay had been about queerness within Swift’s work it would have been a less ethically dubious exercise.

Marks also tries to have it both ways, writing…

… whatever you make of Ms. Swift’s sexual orientation or gender identity (something that is knowable, perhaps, only to her) or the exact identity of her muses (something better left a mystery), choosing to acknowledge the Sapphic possibility of her work has the potential to cut an audience that is too often constrained by history, expectation and capital loose from the burdens of our culture.… and …

… would it truly be better to wait to talk about any of this for 50, 60, 70 years, until Ms. Swift whispers her life story to a biographer? Or for a century or more, when Ms. Swift’s grandniece donates her diaries to some academic library, for scholars to pore over? To ensure that mea culpas come only when Ms. Swift’s bones have turned to dust and fragments of her songs float away on memory’s summer breeze?

I think not. And so, I must say, as loudly as I can, “I can see you,” even if I risk foolishness for doing so.… within the space of a few paragraphs. It’s the op-ed writer’s equivalent of that old Nelly lyric: “I'm just kiddin' like Jason/ Unless you're gon' do it.” Marks wants to say she’s just exploring the sapphic suggestions in Swift’s lyrics while also suggesting pretty emphatically that she believes the star is gay.

In the prologue to 1989 (Taylor’s Version), Swift wrote of the ‘squad’ of other famous women that she surrounded herself with when the original version of the album was released:

If I only hung out with my female friends, people couldn’t sensationalize or sexualize that — right? I would learn later on that people could and people would.”As well as the wider Gaylor theory, a subset of Swift’s fandom has long theorised/ fantasised that she had a secret romantic relationship in 2014 with Karlie Kloss, one member of the squad who she has not been pictured with for quite some time.

While Marks’ essay should have been written differently or not written at all, Swift and her team — especially her powerhouse publicist Tree Paine — should avoid doing a Donovan and protesting too much. A “person close to the situation”, presumably Paine with a stuck-on moustache or beneath a comically large sombrero, told CNN:

Because of her massive success, in this moment there is a Taylor-shaped hole in people’s ethics. This article wouldn’t have been allowed to be written about Shawn Mendes or any male artist whose sexuality has been questioned by fans.

There seems to be no boundary some journalists won’t cross when writing about Taylor, regardless of how invasive, untrue, and inappropriate it is — all under the protective veil of an ‘opinion piece’. Poor old Shawn Mendes must be wondering what he did to be dragged into all this. Anyway, as Marks’ Harry Styles essay shows and the long-running fan speculation about him and his One Direction bandmate Louis Tomlinson (the ‘Larry’ ship) confirms, male pop stars are not shielded from that kind of coverage.

Marks attempted to preemptively address critics in the essay, writing:

I know that discussing the potential of a star’s queerness before a formal declaration of identity feels, to some, too salacious and gossip-fueled to be worthy of discussion.”

I share many of these reservations. But the stories that dominate our collective imagination shape what our culture permits artists and their audiences to say and be. Every time an artist signals queerness and that transmission falls on deaf ears, that signal dies. Recognizing the possibility of queerness — while being conscious of the difference between possibility and certainty — keeps that signal alive.The problem is I don’t think she was nearly conscious enough of the difference between possibility and certainty. Despite her wealth, status, and cultural cache, behind the brand, Swift is another human being. Marks forgot that in service of her thesis and did so on one of journalism’s biggest stages.

Please consider sharing this edition if you enjoyed it:

You can also follow me on Threads, BlueSky and/or TikTok.

If you haven’t yet, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. You’ll get bonus editions and other exciting developments in 2024.

It helps and allows me to spend more money on research and reporting. Buy a t-shirt if you’d like to make a one-off contribution and get a t-shirt

That’s outrageous. Just because someone is in the public eye (and happens to be massively successful) doesn’t give “journalists” the right to speculate on any area of their life, if it isn’t actually in the public interest. Kylie is a gay icon but is clearly not, herself, gay.

Compare coverage of Andrew Windsor, who has, seemingly, done very bad things, which the public do need to know because he receives public money.

Thank you, Mic.

Excellent piece, Mic; it’s the holier-than-thou tone of the article as well as the hatchet job that disgusts me. Will post on X