Mapped out.

The response to illustrating connections in the British media says much more than the original project.

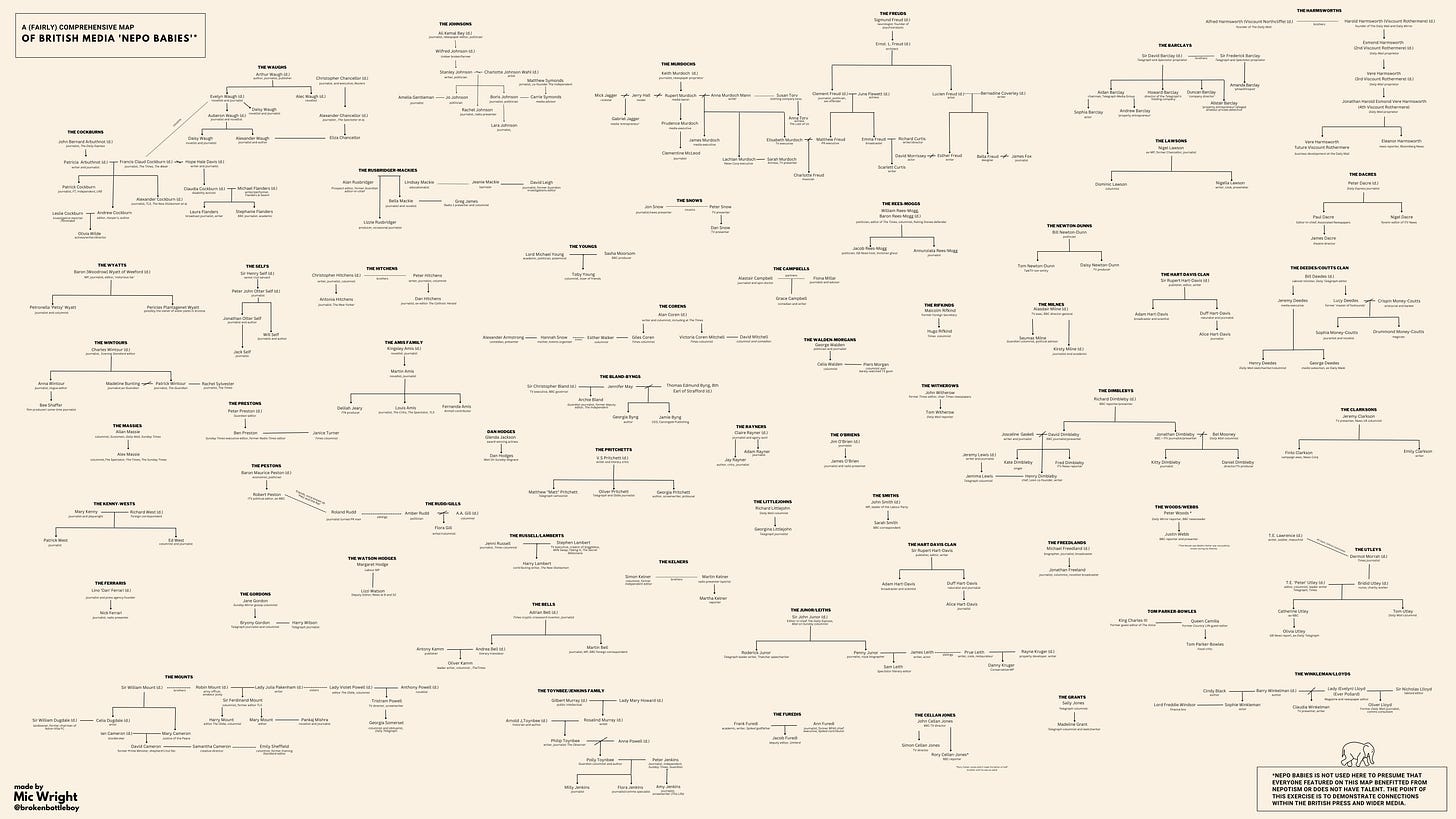

This edition is about a diagram — a map — I created to illustrate connections in the British press and wider media. Here it is:

You can find a fully zoomable and downloadable PDF version here.

How a Nepo Baby Is Born Hollywood has always loved the children of famous people. In 2022, the internet reduced them to two little words

New York magazine, Dec 19 2022

The inevitable rise of ‘nepo babies’

The Times, Dec 22 2022

UK politics is filled with ‘nepo babies’ from Hilary Benn to Andrew Mitchell,

the i, Dec 26 2022

Eve Hewson: Fans rally around actor as she shares post about being the ‘nepotism baby’ of a famous father, The Independent, Dec 26 2022

Lottie Moss fires back at nepo baby criticism: ‘Guess what? Life isn’t fair,

The Independent, Jan 2 2023

The ‘nepo babies’ heading up some of the UK’s most successful corporations,

Raconteur, Jan 20 2023

A Rough Shortlist of the UK's Showbiz Nepo Babies

Vice, Jan 25 2023

American Nepo Babies Have Nothing on the British

Vice, Jan 25 2023

‘Nepo babies’ claim their parentage is overblown [but] they’re helped all the way

The Observer, Jan 29 2023

After New York magazine — a product of Comcast (where the hereditary CEO, Brian L. Roberts, is the son of the company’s founder Ralph J. Roberts) — published a series of articles about Hollywood 'nepo babies'1, the British media leapt on the idea. Features and comment pieces considered entertainment, the legal profession, (some) corporate bosses, and politics, but there was the elephant in the room whose stamping and defecating went unacknowledged: The British media itself.

People in the comments beneath The Times follow-up to the New York story — published three days later — noticed how carefully it avoided mentioning journalists:

Matthew Andrews

21 DECEMBER 2022

She's genuinely ignorant if she thinks that financial services and law firms don't bend over backwards to avoid this (other than, for obvious reasons, in family firms). Whereas arts and the media appear to see this as normal. Perhaps Mr Coren could provide additional commentary.

J Wright

21 DECEMBER 2022

Bit of an elephant in the room here isn’t there? Giles and Victoria Coren clearly didn’t benefit at all from the fact that daddy was a famous journalist. In fact, as she is the same age as me, I remember this very paper printing Victoria’s column as a 15/16 year old. Strangely I wasn’t offered the same opportunity — my dad was only a butcher!When Vice published A Rough Shortlist of the UK’s Showbiz Nepo Babies which, by definition, swerved journalists, the piece was gleefully shared by lots of people in the British media. Seeing that, as well as the blinkers-on responses to the New York cover story, I decided to make a map of connections in the British media.

Investigating the shared characteristics and connections of a group of people — prosopography — has a long history. While the term was used by historians in the 19th century, it was brought into more common usage by Professor Lawrence Stone in an article in 1971:

Prosopography is used as a tool with which to attack two of the most basic problems in history. The first concerns the roots of political action: the uncovering of the deeper interests that are thought to lie beneath the rhetoric of politics; the analysis of the social and economic affiliations of political groupings; the exposure of the workings of a political machine; and the identification of those who pull the levers.

The second concerns social structure and social mobility: one set of problems involves analysis of the role in society, and especially the changes in that role over time, of specific ( usually elite ) status groups, holders of titles, members of professional associations, officeholders, occupational groups, or economic classes; another set is concerned with the determination of the degree of social mobility at certain levels by a study of the family origins, social and geographical, of recruits to a certain political status or occupational position, the significance of that position in a career, and the effect of holding that position upon the fortunes of the family; a third set struggles with the correlation of intellectual or religious movements with social, geographical, occupational, or other factors. Thus, in the eyes of its exponents, the purpose of prosopography is to make sense of political action, to help explain ideological or cultural change, to identify social reality, and to describe and analyze with precision the structure of society and the degree and the nature of the movements within it. What I’ve done is a very basic version of that; I combined personal knowledge, tips, chasing blue links on Wikipedia, and research with online and print sources to create a snapshot of some connections in the British media. I collated public information — it’s not secret or arcane knowledge — and, inevitably, I included some jokes.

As you’d expect, it’s been received by Britain’s rhino-skinned journalists with the quiet dignity for which they are renowned.

The responses have included implying I’m mad — keep an eye out for mental health awareness posts from those hacks in the near future — and obsessive (guilty), loudly saying “no one cares” while caring deeply, claiming “everybody knew this” even as lots of people outside the industry express their surprise, getting specifically annoyed that a favourite is included on the chart, and attempting to smear me personally.

The ‘best’ example in the latter category came from Ned Donovan2, the ex-Daily Mail journalist son of a journalist, grand-son of Roald Dahl and brother-in-law of the King of Jordan3. The fact that I’m middle class, went to a private school — something I fully accept is a huge issue in the British media — and once worked on a disastrously unsuccessful website project with my mum (who isn’t a journalist4) means, according to Donovan, that I am the same as people whose families have dominated journalism for decades, if not centuries.

Donovan’s clumsy Columbo act — “Just one more thing!” — was jumped upon by a small number of people on the left who believe that you must be a perfect person to make any comment on society, allying them to the hacks who were making the same argument from the opposite direction.

There were also those whose argument was “well, this chart only shows one problem and it’s not even the biggest problem”, as though lots of the issues with journalism aren’t implicitly represented by those connections if you look at them for more than a moment. Using the word “nepotism” can lead to the conclusion that it’s the only or biggest issue; it’s not. Privilege extends beyond this and the map indicates that.

Then, of course, there were people who said, “so what? Lots of people follow their parents into the same profession,” as if the press and wider media don’t occupy an unusually privileged and powerful role in society.

Being on the map doesn’t mean someone isn’t talented but there are plenty on it who aren’t. It isn’t designed to make value judgements, be totally comprehensive, or serve as a final say on the arguments it provokes. It’s a chart designed to illustrate a phenomenon, but the antibody response from hacks — those who have benefitted from connections and those who haven’t — is revealing.

It’s worth saying there are lots of journalists who saw the point of what I was doing; plenty of them sent me suggestions after I posted the first draft and have messaged me both publicly and privately about the project. Some people featured on the map have been extremely gracious about it, notably Bryony Gordon of The Telegraph who told me she should be included, Henry Dimbleby who sent me a funny tweet about it, and Archie Bland of The Guardian, who wrote:

I aim to be the Allison Williams of UK media nepo baby discourse.Bland is referring to how Williams — the daughter of famous newscaster Brian Williams — addressed her own advantages in a recent Wired interview:

It doesn’t feel like a loss to admit it. If you trust your own skill, I think it becomes very simple to acknowledge.

[When I was younger, it] made me feel really defensive because the subtext of that is you’re not very good. And now as an older person who’s been at this longer, I feel like I know there are people who don’t think I’m good.

I’m not for everybody and so letting go of that means it’s much easier for me to also say if you also are wondering that perhaps my relationships helped me get in the door and get me where I am then the answer is 100% yes and I don’t feel like I’m losing anything by admitting that. It’s totally unfair in a way that’s maddening so to be told that it’s not real and it’s not happening, is just gaslighting. The problem is that most journalists and media figures who have benefitted from a level of elite connections respond more as David Dimbleby did in an interview with the BBC’s Hard Talk in November last year:

Stephen Sackur: Do you feel, if you were setting out on your broadcasting career today, that you’d find it as easy to become the ‘top dog’ at the BBC in the way that you did?

David Dimbleby: No, I’m sure not.

Sackur: In a funny sort of way it’s worth just exploring your own past, it’s quite telling about BBC past and present. You were the son of the BBC’s, perhaps, most famous presenter of the time. A man who had been a war correspondent in World War II. Then, I think, was presenter at the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth. He was, in many ways, the voice and the face of the BBC, that you were to become. It feels a bit nepotistic that you ended up doing pretty much the same job that your dad did.

Dimbleby: What’s nepotism? How do you define it?

Sackur: Nepotism is when your family pulls strings to get…

Dimbleby: My dead father, who died in 1965, was pulling strings for me in 2020?! Come on, you must be joking!

Sackur: No, no, no, not literally up to 2020.

Dimbleby: Well, you asked the question.

Sackur: I did and it’s a serious question…

Dimbleby: No. I tell you what I think… I came into broadcasting when I was 12 years old to the BBC… I did Family Favourites. And I did work in the BBC pretty well all my life; I went to university and then I started as a reporter in Bristol. And the name Dimbleby is a funny name, it sounds odd and there aren’t many of us in the country — Sackur is quite a strange name too — but if I’d been called Smith, nobody would have said it was nepotism.

And I’m sure at the very beginning, at the very very beginning — and the BBC was a very small organisation then — people thought “well, let’s give this bloke a try and see how it goes…” You wouldn’t last 60 years on that basis. It’s interesting that the Dimbleby family has been in journalism for so long. I mean, my great-grandfather was a journalist. We are journalists by trade. My son’s doing it now. The fury and myopia of Dimbleby’s response is a common pattern. It is extraordinarily hard to get people who were handed stilts at the start of their careers in journalism to admit that it was not simply talent and grit that powered them through or that when they got that job, someone less connected but as capable did not.

Tom Newton-Dunn’s swiftly deleted 2019 Sun front page splash Hijacked Labour, which was based on an unhinged network map which drew on ‘research’ from fascist groups such as Aryan Unity, caused him no professional issues because it targeted left-wing writers, journalists, and activists. Me collating factual information has triggered ‘you’ll never work in this town again’ reminders as if I wasn’t already aware of that.

The map is a minor thing that I made to illustrate one point about the British media but the response to it says so much more. The wagon-circling, smear-threatening, offence-taking, mental-health doubting, eye-rolling unhinged counter-attack does not suggest an industry that is comfortable with itself or proud of how it functions.

It has only made me want to write more. Cartography is oddly addictive.

I normally encourage people to subscribe here. If you can spare the money, here’s the link to donate to the Turkish Red Crescent.

People who have benefited from family connections.

He’s not on the map yet.

Who now works as a Special Constable in London, flying in from Jordan to do it.

And neither is my dad.

Mic - this is brilliant and much-needed. And the Twitter naysayers are only proving that.

I have had cause, very briefly, through work, to associate with Donovan. Was aware at the time of his connections and his shtick; that he was the bedwetter-in-chief about all of this was no surprise at all. Incidentally, can’t help but notice that the puff piece about his special constable duties is bylines simply to “Daily Mail Reporter” - far be it from me to cast aspersions or indulge in conspiratorial

innuendo, but I find the idea of it being by him, anonymously, both funny and entirely in-character.