Just a hunk, a hunk of churning guff: What The Times' "Elvis: The Spy" story reveals about how British newspapers manufacture stories...

"Elvis and President Nixon were in the closet making schemes and I saw one of the schemes and the scheme looked at me!

Did you hear the one about Nixon hiring Elvis Presley as the most ostentatiously attired spy since Roger Moore’s Bond pulled on that yellow ski suit in The Spy Who Loved Me?

If you read The Times yesterday or listened to practically any radio station there’s a decent chance you did.

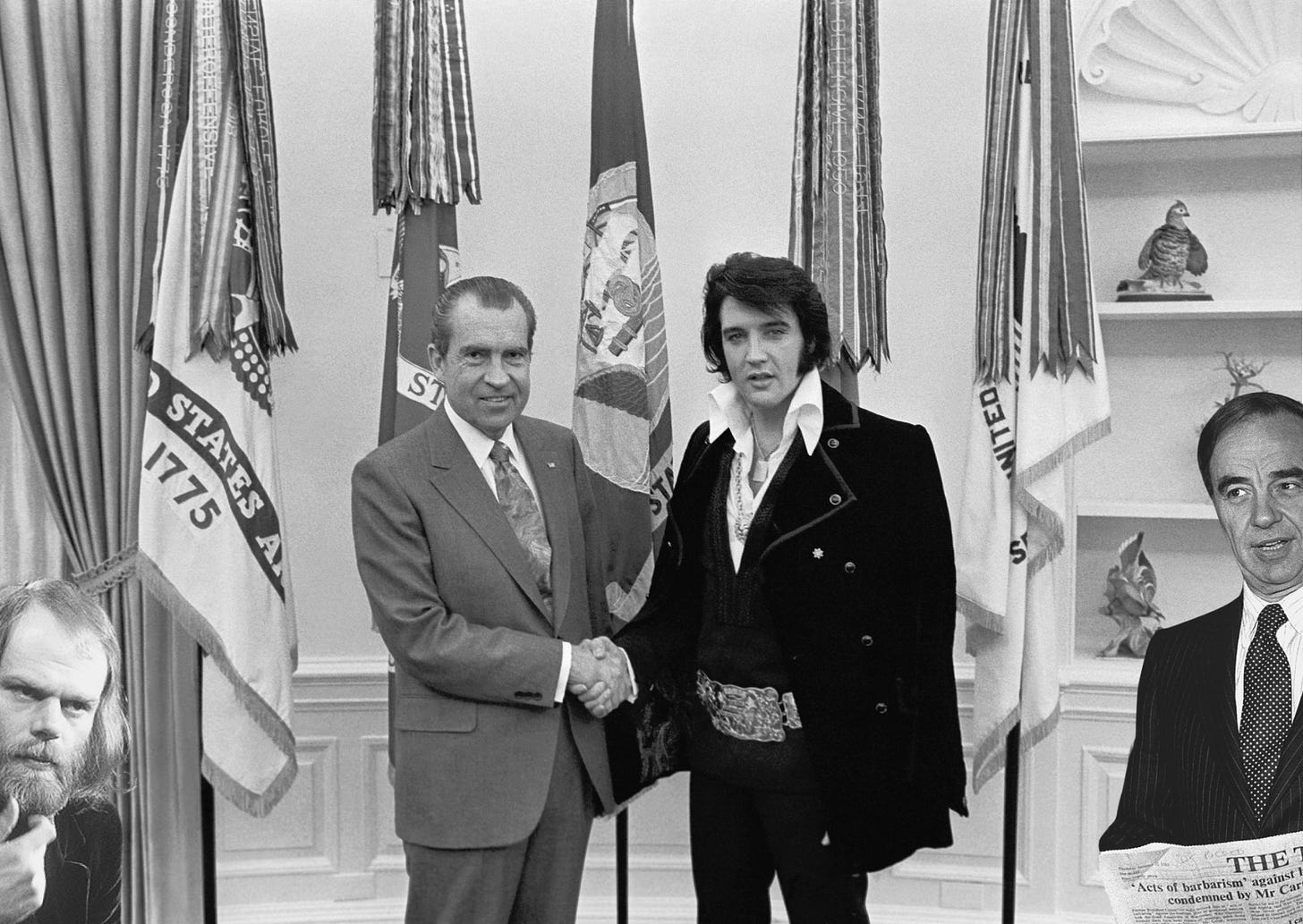

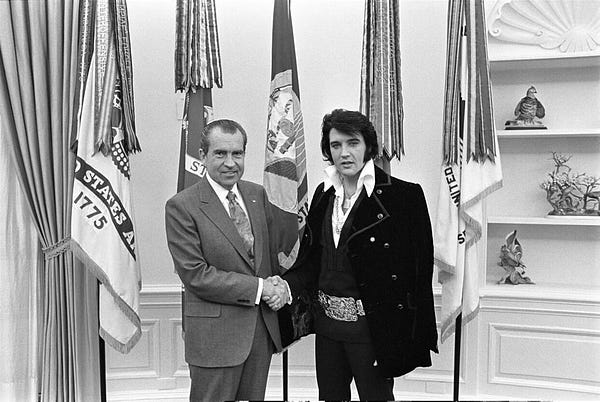

The story of Elvis’ visit to Nixon at the White House in December 1970 is very well known; it was made into a movie — Elvis & Nixon — in 2016 with Michael Shannon as Elvis and Kevin Spacey as Tricky Dicky [joke redacted here for taste reasons], and the photograph of the meeting is one of the most requested items from the US National Archives:

Elvis — dressed in a purple suit with a gold belt, a Colt .45 pistol on his hip — was extremely paranoid about “Communist brainwashing techniques” and told the present he had conducted an “in-depth study of drug abuse”, which was true if you consider prodigious consumption of practically every prescription drug he could get his hands on to be “in-depth study”.

On that day at the White House, Presley carried a personal letter to the Nixon in which he wrote that he had…

… talked to Vice President Agnew in Palm Springs three weeks ago and expressed my concern for our country. The drug culture, the hippie elements, the SDS1, Black Panthers etc. do not consider me as their enemy or as they call it the establishment. I call it America and I love it.

Elvis was a collector of police badges and wanted Nixon to give him a shield from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs and name him a “Federal Agent at Large”. He argued in the letter that he could influence young people if only he were “given federal credentials”. That having that title would come in handy for someone so full of pills that he practically rattled when he walked didn’t come up.

Priscilla Presley, Elvis’ then-wife, was more direct about his intentions in her memoir Elvis and Me (1985):

With the federal narcotics badge, he [believed he] could legally enter any country both wearing guns and carrying any drugs he wished.

There’s no transcript of the meeting and Nixon didn’t have the taping system that would lead to his downfall during the Watergate scandal installed until the following year so most of what we know comes from a memory written by an aide, Egil ‘Bud’ Krogh, who was in the room.

The Beatles make an appearance in that document. Krogh writes:

Presley indicted that he thought The Beatles had been a real force for anti-American spirit. He said that The Beatles came to this country, made their money, and then returned to England where they promoted an anti-American theme. The President nodded in agreement and expressed some surprise.

The President then indivated that those who use drugs are also those in the vanguard of anti-American protest. Violence, drug usage, dissent, protest all seem to merge in generally the same group of young people.

Elvis got the badge he was seeking but, according to former Secret Service agent Clint Hill in his book Five Presidents: My Extraordinary Journey with Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Ford (2016), it was worthless and didn’t have the powers that Presley thought it did. Hill says:

[Elvis] brought a gun in a framed box, which we looked at to make sure it was not any problem. And he presented that to Nixon.

The President then gave Presley the honorary Federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Agent badge. Hill continues:

[Elvis] believed he had some authority, which he did not have. He had no power of arrest or any legal authority whatsoever. [But] he went away happy.

And so we come to The Times’ ‘revelation’ yesterday about Elvis Presley: Secret Agent and the claim that he was tasked by the president to spy on John Lennon. Under the headline How Nixon’s suspicious mind led to Elvis spying on John Lennon, Nadeem Badshah writes:

Elvis Presley was told to spy on John Lennon by President Nixon while the Beatle was living in New York, according to the music presenter Bob Harris.

Harris, who interviewed Lennon on TheOld Grey Whistle Test, his BBC show, said that Nixon “loathed” Lennon for his criticism of the Vietnam war and wanted him out of the country.

Harris, 75, claimed that the president recruited Presley, “a great friend”, to monitor Lennon during the 1970s.

You can immediately see that those three skeletal paragraphs don’t remotely have the muscle to lift that weighty headline. The head promises us the story of what “led to Elvis spying on John Lennon” while the copy just gives us a second-hand take on an anecdote.

The Times and other papers frequently find stories using this method: Taking a line from a podcast and extrapolating it out into a story, giving someone’s words more weight than they intended them to have and leaning on a single source to justify a hyped-up headline.

In this case, the meat of the story comes from Harris’ appearance on Gary Kemp and Guy Pratt’s excellent Rockonteurs podcast. He said:

It sounded like it was almost a figment of [Lennon’s] imagination when he was saying, “My phone was tapped. I get followed everywhere.” — but it was true; he really did. Nixon was out to get him and that’s why John was stuck in New York or stuck in the States: He knew were he to come back to the UK, he’d never get back into America again. Not while Nixon was in the White House.

Up to that point, Harris is simply recounting the facts. Jon Wiener’s book Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files (1999) details his 14-year battle to get access to the FBI’s files on its surveillance of Lennon.

The 100 or so pages that were finally released after the FBI was forced into a settlement when the case made it to the Supreme Court contained reports from confidential informants — snitches, none of whom were Elvis — transcripts of Lennon’s TV appearances, and a plan to have the former-Beatle arrested by local police on drug charges.

But the next part of Harris’ comments on the podcast is where he moves into conjecture. He continues:

Nixon was a great friend of Elvis and vice versa. Nixon had [instructed] Elvis to gather as much information about John Lennon as he possibly could.

There’s no evidence that Elvis and Nixon ever spoke again after that meeting in 1970. It’s possible but Harris doesn’t offer any more evidence beyond what John Lennon told him in off-air chats.

Elvis’ FBI file notes that during a visit to its headquarters 10 days after meeting Nixon, he told his hosts that he would like to advise then-director J. Edgar Hoover “that The Beatles laid the groundwork for many of the problems we are having with young people by their filthy unkempt appearances and suggestive music”. But here’s no evidence that Hoover signed Presley up as a tout.

In fact, unlike Nixon who was willing to humour Elvis in return for a potentially useful photo-op, Hoover refused to meet Presley and, according to Anthony Summers’ Official And Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover (1993), described him as “wearing all sort of exotic dress”.

The Times also quotes Harris’ comments about The Beatles and Elvis’ famous 1965 meeting in Los Angeles. He says that Lennon’s encounter with Presley was “hate at first sight” and led to a “resentful rivalry”:

For John it was a very disillusioning moment because he loved Elvis’s records, so . . . to discover he was a right-wing southern bigot was a big shock. Equally, Elvis saw Lennon as being this upstart Liverpudlian know-it-all who’d taken his crown. He usurped Elvis and he was resentful as hell.

While it’s clear that Elvis did come to despise The Beatles, Harris’ recounting of that 1965 encounter is at odd with the one offered by Priscilla Presley…

… who described an awkward but amicable meeting.

While Harris says Lennon was disillusioned to “discover [Elvis] was a right-wing southern bigot”, Lennon’s own comments about Elvis in the years after they met were harsh but focused mainly on his music and the drift away from rock’n’roll. In an interview featured in Anthology, Lennon said:

… after [Elvis] went into the army, I think they cut ‘les bollocks’ off. They not only shaved his hair off; I think they shaved between his legs, too… Elvis really died the day he joined the army. That’s when they killed him and the rest was a living death.

Lennon didn’t live long enough himself to find out about what Elvis said about The Beatles to Nixon and the FBI, but Paul McCartney said sharply, also in Anthology, that:

I felt a bit betrayed by that, I must say. The great joke is that we were taking drugs, and look what happened to him. He was caught on the toilet full of them! It was sad, but I still love him, particularly in his early period. He was very influential on me.

The problem with The Times piece and the many, many parasitic follow-ups to it is that Harris reflecting on conversations he had with John Lennon 46 years ago is being taken as an unquestionable source. Reporters should never use just a single source, particularly a single source that they’ve not spoken to themselves but simply listened to on a podcast.

The Rockonteurs podcast hosts and their guests were not setting out to write a history book; they were just having a conversation. There are several factual inaccuracies in the first few moments of the section on Lennon, Elvis and Nixon2, but it’s a podcast of anecdotes, not a fact-checked news report.

While The Times frames Harris’ comments with the caution word “claimed”, its headline — which is as far as a lot of people get — writes a very big cheque (Elvis was Nixon’s spy!) which its account cannot remotely pay out on.

Of course, in this case, it doesn’t really matter. One more rock myth is added to the mountain of half-remembered half-truths, joining all the animals that Ozzy is meant to have bitten the head off, the now terribly hackneyed tale of Van Halen and the M&Ms, and those rumours about [redacted], [redacted], or [redacted] having humanly impossible amounts of semen pumped out of their stomach.

But we should expect better from news reporters. Taking Harris’ comments, without subjecting them to even the mildest amount of fact-checking before sticking them beneath a deceptive headline isn’t reporting, it’s stenography. The so-called “paper of record” should try a lot harder to keep the record straight.

That The Times isn’t willing to check the facts on a story about two of the most famous musicians of all time — a task that took me no more than half an hour during the writing of this piece — should increase your scepticism about any news story in that paper. Day in, day out, The Times finds itself with the choice of whether to state the facts or print the legend and it often opts for the latter, especially when yesterday’s legend fits nicely with today’s ideology.

Students for a Democratic Society: A national student activism organisation that grew from its small beginnings in 1960 to over 300 campus chapters and 30,000 supporters before it splintered following its final national convention in 1969.

Not just Harris saying Nixon was a great friend of Elvis’ but also the repetition of the myth that the president really made Presley a federal agent.