In the shadow of 'The Nude Statesman'

The New Statesman played a pivotal role in allowing Russell Brand to remake himself as a 'revolutionary'.

Previously: Just whispers about Wilby

A former editor of the New Statesman and Independent on Sunday was revealed as a paedophile. It hasn't really made the headlines or roused the columnists to rage.

Before you read this edition, I encourage you to watch Dispatches: Russell Brand — In Plain Sight and/or read The Sunday Times investigation into allegations against him.

First, though, I should qualify my right to even pontificate on such a topic and in so doing untangle another of revolution’s inherent problems. Hypocrisy. How dare I, from my velvet chaise longue, in my Hollywood home like Kubla Khan, drag my limbs from my harem to moan about the system? A system that has posited me on a lilo made of thighs in an ocean filled with honey and foie gras’d my Essex arse with undue praise and money.— Russell Brand, The New Statesman, October 2013

In the promo for Russell Brand’s guest stint as New Statesman editor, the magazine’s actual editor, Jason Cowley, hovers in the background, out-of-focus but chuckling. The essay by Brand which dominated the issue — a lengthy burble about ‘revolution’ and the pointlessness of voting — was described by the magazine in its publicity as “a 4,500-word tour de force”. Meanwhile, in a press release, Brand promised his first act would be to rename the magazine to The Nude Statesman.

The ‘star’ editor drew an equally starry list of names to the magazine’s contents page: Naomi Klein on “revolutionary science”; the actor Rupert Everett with an essay on gay rights; Amanda Palmer — a person with her own long list of problematic incidents to review — hyping crowd-funding and “the revolution in artist-audience relationships”; Gary Lineker talking “pushy parents on the touchline” and calling for “a revolution in the teaching of school sport”; a contribution from Noel Gallagher, listing politicians he hates; Alec Baldwin — a man with more red flags than a Soviet Victory Day parade — contributing a profile of Edward Snowden; David Lynch promoting transcendental meditation; Judd Apatow, Oliver Stone, Howard Marks, Martha Lane Fox and others giving their definitions of revolutions; and Graham Hancock — who promotes a wide range of pseudoscientific theories — touting “a revolution in consciousness”.

Appearing on BBC Two’s Daily Politics, Helen Lewis — then-Deputy Editor of The New Statesman — described the experience of having Brand ‘guest edit’:

[Working with him] was everything you’d imagine and more… He came into our editorial conference and just delivered this, sort of, flawless monologue that had us all sitting there going, ‘Wow, that’s really interesting…’ The fundamental point he made was that he goes to football matches, he sees people on the terraces, they’re really excited, they’re really passionate. He sees people campaigning about the closure of an A&E department or a library, they’re really passionate, yet when it comes to national politics, people feel like it happens over there somewhere. They’re not involved in it, they don’t have any say in it …

… We asked him because we like finding people who the perception of them is not how they actually are and slightly changing that. The same thing happened with Jemima Khan; she had great thoughts about free speech and we really wanted to get those across. And she changed the perception of herself through doing the edit. The same thing happened with Russell Brand… We last remembered him as this guy who hosted Big Brother’s Big Mouth, but actually, he’s got some fantastic pieces in there.

Rupert Everett writing on gay rights, for example, was a revelation to me. It’s a really beautiful piece of writing that I would never have read or we never would have been able to commission otherwise. Guest edits are a trade-off: The big name lends the publication fame and access to other famous people while the magazine gives them some measure of credibility (“Look! I’m heavyweight. I discuss politics!”) The truth is that very little editing goes on beside a chat about who to commission and a few pictures of the star staring at some proofs or looking comical sitting at the editor’s desk.

Lewis’ appearance on The Daily Politics was pretty honest about the transaction: Brand got to shift the public perception of him, five years after ‘Sachsgate’ when he and Jonathan Ross called the actor Andrew Sachs and left a series of voicemail messages that culminated with the Ross shouting that Brand had “fucked” Sachs’ grand-daughter and a sing-song faux apology. Meanwhile, The New Statesman was able to commission people like Everett, Lineker, and Baldwin for whom it might not usually be on the radar.

In December 2022, Lewis — now a staff writer at The Atlantic and a maker of radio programmes — returned to the topic of Russell Brand. Following his shift from mainstream film actor, comedian, and presenter to ‘truthteller’, ‘guru’, ‘influencer’ and ‘MSM critic’, considered him in her Radio 4 series The New Gurus. Brand’s brief time as a New Statesman guest editor doesn’t feature in the programmes but promoting the series during a Times Radio appearance, Lewis briefly mentioned it:

[Brand] has gone through a kind of classic guru evolution: He was a mainstream star — he was film star, he was a TV comedian, he had a radio show, all of that stuff, and now he is on YouTube and increasingly a platform called Rumble, which is where you go if YouTube gives you a strike for Covid misinformation. And he is messianic, like, he’s always had that kind of — I first met him in 2013 when he guest-edited The New Statesman — and he always had a huge charismatic presence, incredible, but he’s now harnessed that in the service, really, of this very conspiratorial style… In the same way that Boris Johnson’s Have I Got News For You appearances helped to make him a national figure and to establish the character of ‘Boris’, Brand’s New Statesman guest edit allowed him to shift into a new stage where he was treated as a serious thinker on politics by much of the press and media.

The day before Brand’s edition of the magazine came out, he appeared on Newsnight, with Jeremy Paxman induced to awkwardly quiz him in a hotel room. In an op-ed for The Independent, Simon Kelner claimed that Brand “made Paxman look ridiculous” and wrote that:

It was a classic Paxman interview. On one side was a rather effete figure with an unruly beard who found it hard to take anything seriously, and on the other side was Russell Brand. Paxman's first contribution rather gave the game away. He sneered at the fact that Brand had guest edited an edition of the “New Statesman”. Paxman asked him: what gives you the right to edit a political magazine when you don't even vote? Brand replied in characteristically disarming fashion: he was in the editor's chair because he had been “politely asked by an attractive woman”.

… Most politicians don't lay a glove on Paxman. Brand made him look uncomfortable and faintly ridiculous. And his retort to Paxman's consistent sneering was priceless. “Jeremy, you've spent your whole career berating and haranguing politicians,” he said, “and when someone like me says they're all worthless, and what's the point in engaging with them, you have a go at me for not being poor any more”. A bit of verbal slapstick it may have been, but there was just the sense, when Jeremy met Russell, that some of the old certainties may be shifting.Mark Fisher, inspired in part by the Newsnight interview, made Brand a central part of an essay called Exiting The Vampire’s Castle, which castigated Left Twitter for being insufficiently comradely:

Brand had outwitted Paxman – and the use of humour was what separated Brand from the dourness of so much ‘leftism’. Brand makes people feel good about themselves; whereas the moralising left specialises in making people feel bad, and is not happy until their heads are bent in guilt and self-loathing.

The moralising left quickly ensured that the story was not about Brand’s extraordinary breach of the bland conventions of mainstream media ‘debate’, nor about his claim that revolution was going to happen… For the moralisers, the dominant story was to be about Brand’s personal conduct – specifically his sexism. In the febrile McCarthyite atmosphere fermented by the moralising left, remarks that could be construed as sexist mean that Brand is a sexist, which also meant that he is a misogynist. Cut and dried, finished, condemned.

It is right that Brand, like any of us, should answer for his behaviour and the language that he uses. But such questioning should take place in an atmosphere of comradeship and solidarity, and probably not in public in the first instance – although when Brand was questioned about sexism by Mehdi Hasan, he displayed exactly the kind of good-humoured humility that was entirely lacking in the stony faces of those who had judged him. “I don’t think I’m sexist, But I remember my grandmother, the loveliest person I‘ve ever known, but she was racist, but I don’t think she knew. I don’t know if I have some cultural hangover, I know that I have a great love of proletariat linguistics, like ‘darling’ and ‘bird’, so if women think I’m sexist they’re in a better position to judge than I am, so I’ll work on that.”Sadly, Fisher died in 2017 so is not around to defend, refine, or even reconsider his view of Brand. His take was, however, increasingly common in 2013/14.

In a 2014, Vanity Fair profile, illustrated with black and white portraits by David Bailey, Brand was feted for “[emerging] as a legit political thinker and voice for the dispossessed”. The author of the piece, David Kamp, continued:

… if you’re not caught up on Russell Brand, you probably think of him as I used to, as the frizz-haired, guyliner’d popinjay in Criss Angel hand-me-downs who hosted MTV’s Video Music Awards a couple of times last decade, acquitted himself decently as an oversexed rock star in Forgetting Sarah Marshall and Get Him to the Greek, had one of those short-shelf-life Hollywood marriages (to Katy Perry in his case) that was more about callow impetuosity than love, and then mercifully drifted off our radar, a minor pop-culture irritant who had had his day.

I was among the not-caught-up until about six months before the Paxman interview, which took place in October of 2013. In April of the same year, Margaret Thatcher died, and Brand wrote an assessment of her for The Guardian that was notable both for its virtuosic facility with the English language (“Her voice, a bellicose yawn, somehow both boring and boring—I could ignore the content but the intent drilled its way in”) and for a conspicuous absence of gloating, ding-dong-the-witch-is-dead meanness. “If you opposed Thatcher’s ideas,” he wrote, “it was likely because of their lack of compassion, which is really just a word for love. If love is something you cherish, it is hard to glean much joy from death, even in one’s enemies.”Karp dismisses Sachsgate as “blown epically out of proportion” and the only sharp bit of criticism in the piece comes via a quote solicited from then-Guardian columnist Suzanne Moore:

… for all his talk of prayerfulness and humility, there persists an image of Brand as a bounder and a cad. Does this compromise his credibility with women? I put this question to Suzanne Moore, a liberal, feminist columnist for The Guardian who is, in many respects, politically sympathetic to Brand.

“It’s funny. I have a 13-year-old daughter, and she absolutely adores him—he seems designed for young people who are just getting into politics,” she said. “But he still has this history, no matter how much he cloaks his sexism—and I’ll call it sexism—in this new spiritual talk. He plays this double game, being very self-aware of his past misdeeds, but I don’t know how much respect he has or shows to women.”Later in the piece, Brand offers this defence of himself:

“As for the misogyny thing, I have lived a life and had a frame of cultural references that make that charge quite legitimate,” Brand said when I raised the subject with him. “But as a person who’s trying to live a decent, spiritual life, misogyny is not part of my current palette of behaviors… In a way, redemption is a great part of my narrative. I’m talking about disavowing previous lives, previous beliefs, previous behaviors.”The article ends with Brand giving Karp an unsolicited and unwanted hug (“…an involuntary envelopment in silk, beads, leather, and beard scruff.”)

With his standing in the UK elevated from the depths of the Sachsgate-era, Brand launched his first YouTube series, The Trews — a tedious portmanteau of “true” and “news” — a few months later, promising that he would:

… analyse the news, truthfully, spontaneously and with great risk to [his[ personal freedom.The Trews, which drew guests including Alastair Campbell, Alain de Botton, Naomi Klein and, most infamously, then-Labour leader Ed Milliband in a pre-election chat that led to a Guardian headline/instant meme: Russell Brand has endorsed Labour – and the Tories should be worried.

Also in The Guardian, Brian Logan’s largely positive review of Brand’s 2013 tour Messiah Complex argued:

It's not an intellectually consistent argument – he has a pick'n'mix attitude bordering on the contradictory towards traditional belief systems. And it often detours via florid sex talk, as Brand tells us how much he worships women (the vagina is "the best metaphor for God there'll ever be", hohum), and needless apology for all "the clever things" in the show.

But these are easy to forgive in a set that elsewhere takes aim at the hidden ideologies of the media (how dare it be called "the news" and not "some news"?) and the futility of putting people on pedestals. It's great to see arena-level standup that asks us to think as well as laugh… Over in the comment section of the same paper, George Monbiot hailed Brand as “the best thing that has happened to the left in years” and called him “a refreshing change from the stifling coherence of some of the grand old men of the left”. Brand also had a run of guest appearances during then-Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger’s daily news conferences, sprinkling some stardust around the newsroom.

Having witnessed the change in Brand’s persona from comedian to new cult leader, Monbiot publicly recanted his praise 6 months ago:

… I can scarcely believe it’s the same man. I’ve watched 50 of his recent videos, with growing incredulity. He appears to have switched from challenging injustice to conjuring phantoms. If, as I suspect it might, politics takes a very dark turn in the next few years, it will be partly as a result of people like Brand. It’s hard to decide which is most dispiriting: the stupidity of some of the theories he recites, or the lack of originality. He repeatedly says he’s not a conspiracy theorist, but, to me, he certainly sounds like one.After The New Statesman guest editorship, the readers of yawn-provoking neo-liberal fanzine Prospect voted Brand the world’s fourth most important thinker (after Thomas Piketty, Yanis Varoufakis, and Naomi Klein). He was invited to speak about drug laws in parliament and, inevitably, appeared on Question Time to row with Nigel Farage, another man with fervent fans and a loose relationship with facts.

No one but Brand is responsible for his actions and it is down to him to account for the allegations found in The Sunday Times and Dispatches investigations. The press and media figures acting as though they played no part in aiding a presenter and comedian in his turn towards cultish ‘thinker’ have questions of their own to answer. It was a slide that began when The New Statesman decided to borrow the cheap heat of his fame in return for its ever-decreasing gravitas.

In the press release announcing the guest editorship, Brand said:

This issue will either recapture the glory of JB Priestley's piece which created the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, or plunge the title into despair not seen since it alleged that John Major was giving Downing Street's caterer an unconventional bonus.I think it stands among the most shameful decisions in the magazine’s very long history, but don’t expect Cowley to ever admit that.

Thanks for reading. X/Twitter is one of the main ways people find this newsletter so please consider sharing it there…

… and also think about following me on Threads and TikTok.

Upgrade to a paid subscription to this newsletter, you’ll get bonus editions, and I’ll be able to keep writing these newsletters). It really helps.

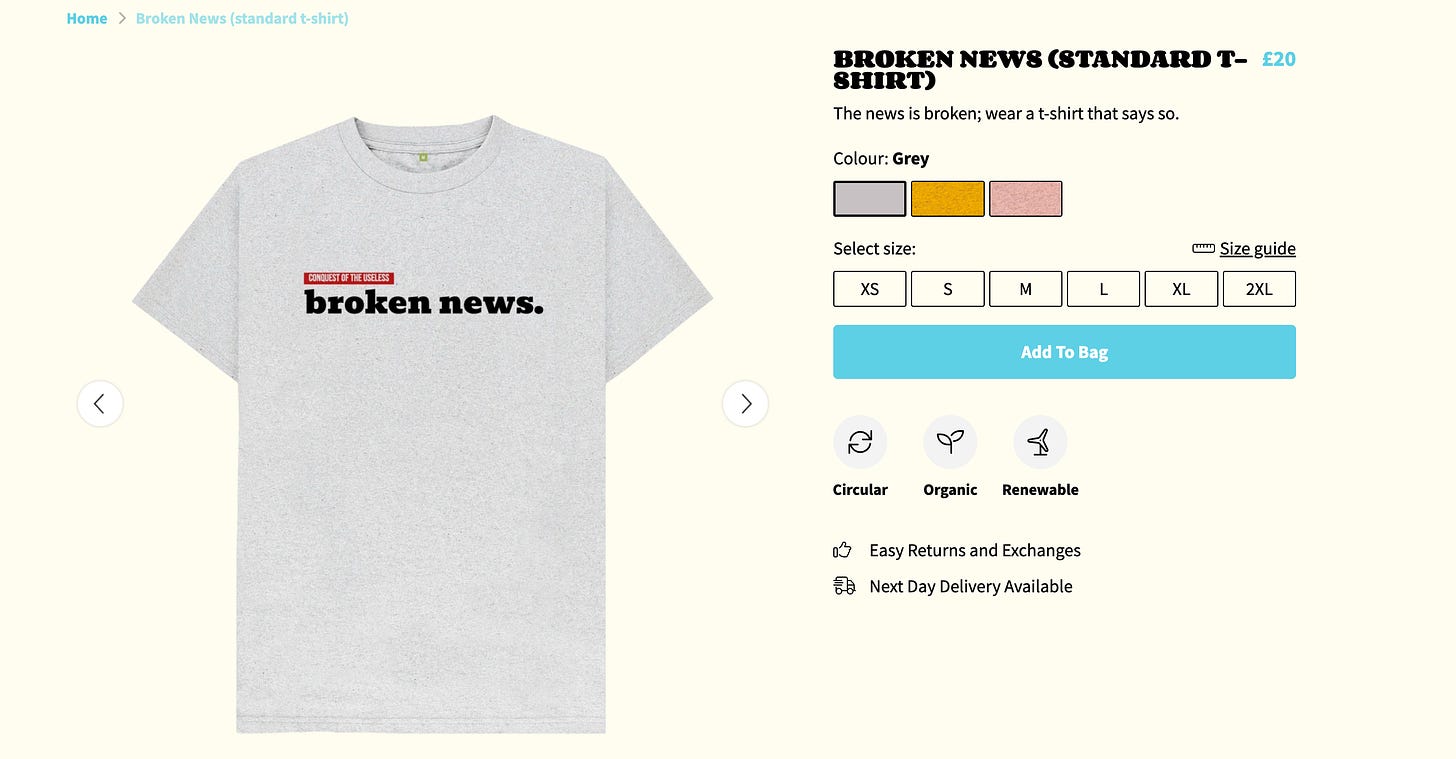

House Ad:

You — well, possibly not you but some readers — requested t-shirts and now I have made some. Head here to see the selection.

For full transparency, I make between £2 and £4 on each item.

I think Joe Kennedy was pretty positive about Brand in Authentocrats, holding him up as an alternative example of the 'working class' to that conjured up by Blue Labour, etc