Hog heaven for war pigs: The grim spectacle of newspaper militarism again reveals the hollowness of War Christmas

Eager essays on war, garlanded with clipart poppies, and a slurping interview with the Chief of Defence Staff from the flag-shagging Tom Newton-Dunn have absolutely nothing to do with "respect".

Despite his pathological biscuit obsession, Cookie Monster has his priorities right: He wears the poppy; he gets that one poppy equals one respect. The evidence of the furry blue monster’s regard for remembrance is preserved in the amber of an early-evening magazine show appearance.

On Monday, November 7, 2016, Cookie Monster appeared on The One Show, perched next to the equally poppied-up Chris Tarrant and interviewed by poppy-sporting hosts Matt Baker and Alex Baker, with a poppy carefully pinned straight on his bright blue furry chest.

Cookie Monster, who requires someone’s hand up his arse to create an impression of sentience — something he shares with most backbench MPs — had to wear a poppy because appearing on air between late-October and November 11 without one is guaranteed to produce a storm of correspondence from red-faced viewers keen to police other people’s remembrance.

While the BBC’s guidelines say wearing a poppy is a personal choice for both guests and presenters — it suggests only the time frame when poppies should appear (between October 26 and November 11)1 — presenters know that going without one is guaranteed to earn you an appearance in the pages of The Daily Mail and Daily Express.

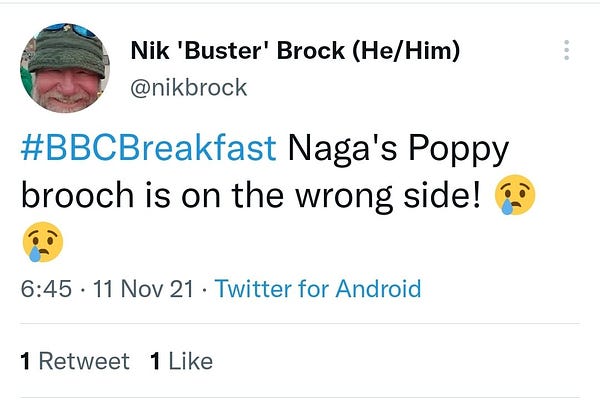

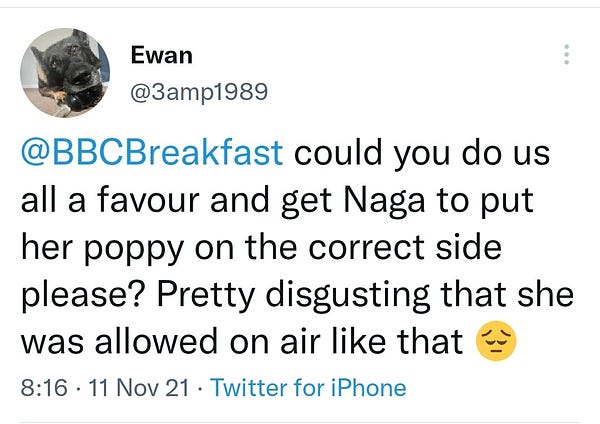

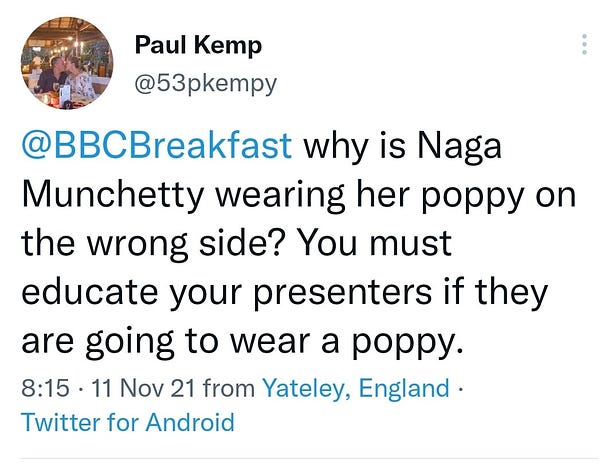

If those presenters happen to be people of colour like Naga Munchetty on BBC Breakfast wearing a poppy still isn’t enough.

The self-appointed poppy police, having respectfully turned their front gardens into recreations of the Somme and covered every inch of their own bodies will poppy, will write in furtious that the host is not wearing the poppy correctly, even though the Royal British Legion says there isn’t a correct way. It’s almost as though poppy placement isn’t what the complainants are objecting to…

Joe Glenton, the journalist and former soldier whose new book Veteranhood is a timely and necessary corrective to the cant and hypocrisy of the War Christmas industry, puts it well:

It’s that time of year again when we solemenly remember the war dead by dressing our children up as giant poppies, cosplaying as First World War soldiers, decorating our gardens with mannequins dressed up to look like soldiers who died in the trenches.

To me, it’s like a symbol of obedience, and remembrance is a kind of carnival obedience, military obedience… at some point back in the mists of history, the red poppy symbolised almost insurgent grief and sadness. It’s probably the only sense in which I’m a conservative, is that I kind of want remembrance to be serious again…

On the eve of Remembrance Sunday, the right-wing press thrums with examples of that “carnival obedience” that Glenton talks about. I’m going to look at three of them in today’s edition:

Two from The Times — former Sun Defence Editor Tom Newton-Dunn conducting a well-oiled handjob of an interview with the outgoing Chief of the Defence Staff, General Sir Nick Carter, and an essay by Sir Max Hastings on “the warrior spirit” — and one from The Daily Mail (a typically cartoonish contribution from Dominic Sandbrook).

Carter’s comment to the defence select committee earlier this week (“Part of the reason we encourage a laddish culture is ultimately our soldiers have to go close and personal with the enemy.”) provides Newton-Dunn with a way to provoke the headline: “Laddishism? We need people to win in battle, not who are out of control”

After trying push the general into a provocative quote about culture war topics…

How about a recent edict in some MoD meetings where participants are told to give their pronouns as they introduce themselves? Has Carter ever stated he is a he/him? “Er, it’s not something I’ve personally done, and that’s not because I necessarily disapprove of it,” he says, before adding with a smile: “I mean, it’s been easier if you’re just called general.” This is not the first time in Carter’s three years at the top that he feels he has been selectively quoted.

… Newton Dunn takes us on a tour of Carter’s military career: A Winchester boy fails to get into Oxford or Cambridge, heads to Sandhurst because his father “did not approve of redbrick universities”, and is commissioned into the Royal Green Jackets aged 19 in 1978. No punk for little Nicky.

Carter tells Newton Dunn about his first deployment to Northern Ireland…

… the very first day I was there, I was stuffed out on an ambush on some bridge on the road to Londonderry2.

That gives Newton Dunn a chance to raise what he calls “former soldiers dying, such as Dennis Hutchings at the age of 80 last month, while still under the cloud of prosecution for events in the Troubles that can date back almost 50 years". Carter says it “deeply saddens [him]” and Newton Dunn finds no space in his copy to note that the “event” that brought Hutchings to court was the killing of John Pat Cunningham, a vulnerable adult, who was shot in the back, aged 27.

Shifting to Afghanistan — a conflict that Newton Dunn covered for The Sun, in between handing out copies of the paper to the troops — the piece accepts Carter’s rhetoric at face value ("I will always argue that we weren’t defeated on the battlefield. People whould be very proud of what they archieved against a very cunning, ruthless and innovative opponent.”)

Newton Dunn then tries to nudge the general into giving him an indiscrete scoop on the ‘next war’:

With just weeks to go as defence chief, there may still be one crisis left for Carter to have to deal with. Tensions are rising fast on Poland’s border with Belarus over a wave of mass migration orchestrated by Minsk with — it is believed — Russia’s firm encouragement. While saying that “nothing would surprise me these days” over President Putin’s destablising, Carter also sounds caution and warns that there is “a greater risk” of an accdiental war with Russia now than at any time during the Cold War.

The pseudo-seriousness of Newton Dunn’s questioning is undermined by the insistence that a “quick fire” round should be included. Doesn’t it tell you so much about Carter that he prefers Dad’s Army to ‘Allo ‘Allo! and Sean Connery over Daniel Craig?

There’s no space for questions on the disgusting state of military housing, why the British Army’s new Ajax tanks are causing sickness, or The Times’ own run of stories about the murder of a Kenyan woman, the involvement of British soldiers, and allegations of a cover-up.

But Newton Dunn, who says his proudest achivement at The Sun was pushing Help for Heroes and the paper’s ‘Millies’ military awards, is not employed to be critical of the powerful or ask tough question about “our boys”. Instead he delivers a puff piece, a soft-soap profile of Carter who will soon be in the Lords, another ex-general who can take the Tory whip.

While Newton Dunn takes pages 48 and 49 for his interview, two spreads earlier Hastings’ essay — Cherishing the warrior spirit can seem like a losing battle — rummages through history to construct a defence of sorts for Carter’s “laddish culture” comments. It also serves as an advert for Hastings’ new book.

After dedicating the essay’s first half to examples which support his premise that “more than a few warriors relish their work”, Hastings attempts to lash together two ideas:

1) “…that given what [we demand of soldiers] and the number recruited from disastrous home lives, what is remarkable is not how many commit crimes, but how few”

2) “Yet it is unacceptable to offer any excuse of mitigation for brushing beneath the mess carpet such ugly episodes as the 2012 murder of a Kenyan woman, allegedly by British soldiers, and more recent atrocities in Afghanistan for which nobody has been charged.”

Hastings deserves credit for saying what Newton Dunn, a man intoxicated by access, did not have the courage to in his conversation with Carter. But when he writes that “the challenge, for armies in all ages, is to cherish warrior virtues, while rejecting warrior excesses”, he’s indulging in fairytale logic, the “carnival obedience” that Glenton rightly disdains.

When Hastings writes…

Today, there are not only far fewer British warriors, there is also much less public understanding of what being a soldier means.

… there is so much to unpack in those 22 words that I could fill another edition analysing them. Successive governments have underfunded, mistreated, and discarded veterans, increasingly indulging in symbolic veneration in place of better pay, conditions, and after service care. Hastings thinks people do not understand what it is to be a soldier but perhaps the fact that they do is why there are far fewer people willing to sign up for that life.

At least Hastings’ essay is not hack. The same cannot be said for Dominic Sandbrook, a historian whose output was described by Clive James as “things his parents told him”. Now engaged in writing a series of children’s books — including, conveniently, Adventures In Time: The First World War — Sandbrook’s essay bears the crass headline This Is How War Starts and attempts to yoke the current situation on the Poland/Belarus border and a slapdash schoolbook recounting of the origins of the First World War.

In an effort to get The Daily Mail’s permanently paranoid readership to shift to DementedCon 1, the lede reads:

Troops and weapons mobilising at Europe’s borders, a Russian autocrat eager to show his strength, a toxic climate of hubris, fear, and distrust… as we prepare to honour our fallen, a top histrian says the echoes from history have never been so chillingly pertinent.

Putting aside that “a toxic climate of hubris, fear, and distrust” is a beautifully economical description of the Daily Mail newsroom and its editorial values, the parallels Sandbrook attempts to draw between 1914 and 2021 are tenuous at best. Vladimir Putin is not Tsar Nicholas II, the alliances of the European Union are not those of the continent at the dawn of the 20th century, and Boris Johnson isn’t Herbert Asquith (though I could well picture him trying to cop off with his daughter’s best friend3).

There’s nothing in Sandbrook’s essay that will be unfamiliar to anyone who did history at a British high school at any point in the past 50 years. His pen portrait of Gavrilo Princip, the man who killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in particular might as well have been done in broad strokes of Crayola. For Daily Mail readers trained to drool over the lives of aristocrats, Princip must be a simple terrorist and Ferdinand his unfortunate victim.

Slog through all the cliches and received wisdom and you’ll reach this headache-inducing paragraph:

Was it worth it? The debate will never be settled, but the lessons are surely clear. Today, more than ever, the Western world needs clear decisive, unambiguous leadership. Impulsive posturing and naive adventurism are just as dangerous as spineless appeasement and vague good intentions.

Was. It. Worth. It? 20 million dead and Dom wonders if it “was worth it”. And after writing about a meat grinder war that chewed up conscripts in battles for the smallest of gains, Sandbrook implies that a new war would be preferable to “spineless appeasement and vague good intentions”. He elides World War II — a war of survival — with World War I — a war of imperialism — and even as he does remembrance by rote (“…we should remember them.”) he gets into an excited sweat about the prospect of conflict to come.

In a newsletter edition that began with a puppet sporting a poppy, Dominic Sandbrook still somehow manages to be the most ridiculous character.

Oddly poppy-wearing doesn’t feature in the BBC’s ban on ‘virtue signalling’

We call it Derry in this household and in this newsletter.

It’s unlikely that Boris Johnson would bother writing hundreds of letters to someone he was trying to jump, however.