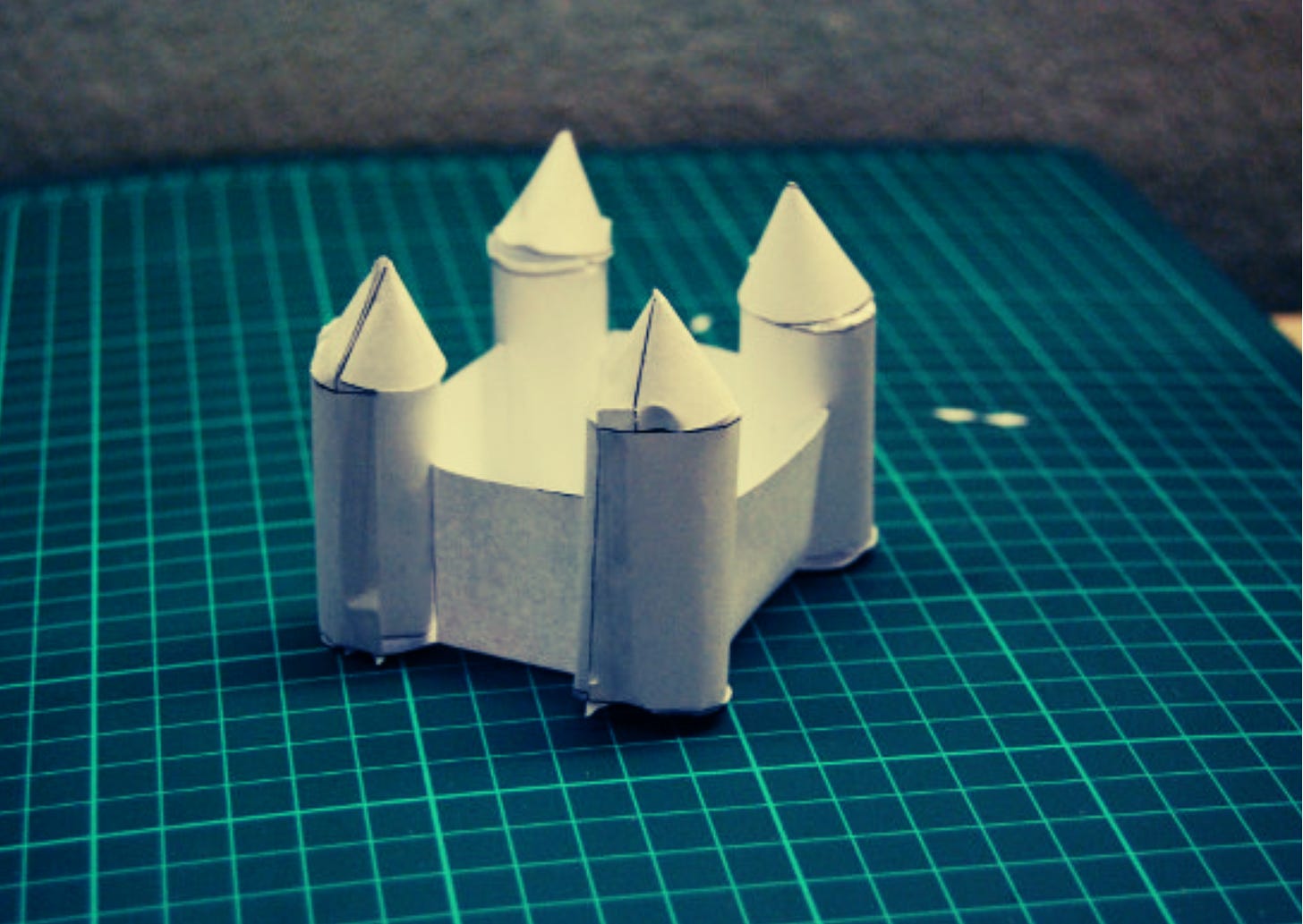

The origami castle

Lots of 'clever' columns can't survive a light rainstorm, let alone a hurricane of piss...

Previously: Stacked against you

A Times columnist's move to Substack was aided by VIP treatment and comes with insulting metaphors.

As an arsehole of many years standing, I cannot resist coining neologisms and phrases that sum up an aspect of reality for me. The latest one that is rattling around my brain is “the origami castle”. It describes a column or any other piece of writing which, at first glance, appears to be elaborate and impressive but which, on closer inspection, cannot stand up to scrutiny.

The Times newspaper is a constant source of origami castles; its stable of op-ed writers is stuffed with people who were told they were exceptional at school and have never got over the serotonin boost. Those eggshell egos are not helped by comments sections full of people who are just delighted to have their prejudices confirmed by someone with a byline picture.

Let’s look at two Times columns to illustrate the origami castle concept but also because they really pissed me off; it’s a twofer!

Juliet Samuels, The Times’ newly-hired central midfielder — brought in to replace David Aaronovitch who has lost several yards of pace since the Iraq War — writes under the headline Politicians should take a hint from the King that:

What [republicans/liberals/’globalists’] don’t grasp is why the institution at the centre of this weird ritual [i.e. the coronation], the monarchy, has lasted on and off for more than a thousand years. It is because it embodies ideas that are necessary to keep together a community beyond the immediate sphere of family and friends. Ultra-liberals tend to take for granted the idea that humans can and should be loyal to an abstraction like “humanity” or “freedom”, but this is not at all obvious. In fact, our everyday lives are ruled by personal relationships, chores and emotions. Collective loyalty beyond this is built by communal experiences — like the coronation — shared culture and a sense of who would stand with us in the face of adversity or attack. The only political unit that commands this abstract sense of loyalty is the nation.That is all said with such confidence that from a distance it looks to have the impressive ramparts and towering walls of a castle built to withstand the winds of trendiness and fashion. But get closer and you’ll see the ramparts sagging; this is an origami castle.

Take the first sentence of that section with its statement that “[the monarchy] has lasted on and off for more than a thousand years”; what has lasted? The idea, perhaps, but it has changed substantially, sloughing off the “divine right” stuff when that became untenable and having much of its actual power drained away by parliamentary bloodlettings. But has the family lasted? Of course not.

For years, the most murderous bastards on the island bumped each other off for legitimacy and eventually ‘we’ — those with power — had to import a bunch of unwanted Germans, Greeks, and other assorted continental crown-wearers to become ‘the British Royal Family’. In World War I, one branch of the family ‘ruling’ the UK fought another leading Germany before a third branch was killed by the Bolsheviks when the British cousins decided that the Tsar would be a pain in the arse if they saved him and his children.

Samuels asserts that the coronation is ‘a communal experience’ but we know that Queen Victoria’s was a damp squib and many before it had barely been bothered with. The pageantry we are stuck with now is a product of public relations and the realisation that a degree of razzamatazz is required to keep eyeballs on the firm and maintain a general level of support (even as it slumps among the young). Just because establishment voices like Samuels tell us the royals brings us together does not make it true.

On the same set of editorial pages, James Marriott (see previous editions) offers a lot of reckons strung together as a theory, provoking a similar set of questions to Samuels’ piece, namely: “What the fuck are you talking about? And why are you so confident about it?”

Marriott’s piece arrives with the headline and lede…

Sorry, we can’t all be destined for greatness

Unrealistic pressure to be ‘special’ is fuelling an epidemic of unhappiness in younger people

… which — he would immediately retort — he does not write. But what he did write is…

I spent much of the past week visiting various university campuses speaking to students. A poignant experience. Partly because I got to waft around other people’s arts faculties, remembering when I too had all that freedom and all that time ahead of me. But this was also the first time I noticed that generational differences now separate me from the current cohort of undergraduates. I was taken aback (and also rather charmed) by how many of my interlocutors eagerly offered me earnest, unprompted explanations of their neurological and sexual identities. I also noticed a new, intense atmosphere of personal ambition. Students fretfully explained that “side hustles”, multiple internships and strenuously cultivated hobbies were no longer the preserve of a hyper-ambitious minority but the basic criteria of success.

I think the new mood I detected might be described as an ethic of exceptionalism. In the 1950s, only 12 per cent of teenagers agreed with the statement “I am an important person”. Today, that figure is higher than 80 per cent. Two thirds of modern students believe themselves to be academically above average, compared with about half at the beginning of the 1970s. It should be said that self-belief is often an attractive trait and not to be deplored in itself — I was thoroughly charmed by everyone I spoke to. It is also true that the explosion of new sexual and neurological identities reflects a richer culture of personal expression. And nobody of a truly liberal sensibility can really object to that. But I do wonder whether these new freedoms of self-realisation don’t carry with them a pressure to be distinctive and extraordinary that is rather punishing.

Modern society puts an unprecedented and flattering emphasis on the potential of the individual. From every angle, our culture feeds our dreams of outstanding personal significance. A recent study found that the phrases “believe in yourself” and “express yourself” occur twice as frequently in modern books as in those published 50 years ago.This combination of anecdata — anecdote elevated to fulfill the role of proof — with a ‘theory’ (most likely developed in the hours before the column was due) and some scrabbled-together quotes and figures is a classic Marriott move. It is what makes him one of British media’s most reliably frustrating origami castle builders. From a distance or in a rush, his arguments sound quite compelling and sometimes even novel. But on closer inspection the castle is graffitied, the paper is soggy, and there is an acrid smell of piss in the air.

The European Correspondent for The New Statesman, Ido Vock, beat me to checking the “12 percent of teenagers…” statistic and, as if often the case with origami castles, it’s built on foundations of sand and unwarranted self-assurance.

The stat that Marriott relies on comes from a talk by David Brooks — a builder of origami castles at The New York Times — who used it in a 2011 talk at the Aspen Ideas Festival (imagine how unbearable the people at that must be):

In 1950 the Gallup Organization asked high school seniors “Are you a very important person?” And in 1950, 12 percent of high school seniors said yes. They asked the same question again in 2006; this time it wasn't 12 percent, it was 80 percent.

Writing for Salon in 2015, David Zweig discovered that Gallup had no record of such a survey and that Brooks had gone on to repeat the zombie fact in his 2015 book The Road to Character. Zweig investigated further and discovered:

I then contacted two of the authors of the paper, Cassandra Newsom, a professor of pediatrics, psychiatry, & psychology at Vanderbilt University, and Robert Archer, a professor of psychiatry at Eastern Virginia Medical School. Abstracts and studies in general can be a challenge for the layperson to read, as academic text is often as opaque as legalese. So they sent me the actual paper and I went through it over the phone with Newsom. Here’s where things really began to unravel.

Newsom explained that, indeed, the first data set was from samples taken in 1948 and 1954, not 1950, and the second data set was from 1989, not 2005. Also, the first data set was exclusive to Minnesota, where respondents were disproportionately white, while the second was a more heterogeneous national sample. The respondents were not high school seniors, as Brooks wrote: In the ’48 and ’54 set, respondents were ninth graders; the 1989 sample was composed of 14- to 16-year-olds. (The ’48 and '54 data set was later sifted to match the 1989 set by including only ninth graders who were aged 14-16.) Lastly, in the 1989 set, 80 percent of boys answered “true” to the statement “I am an important person,” and 77 percent of girls said true. Yet Brooks cited 80 percent as the only figure. I asked Newsom if it was possible that some other study was done in 2005 with the same “I am an important person” question. She said there has not been another normative sample since 1989.In the so-called ‘paper of record’, James Marriott is retrenching a false notion — debunked 8 years ago — and is being praised to high heaven by other ‘public intellectuals’ (and Times contributors) including Dominic Sandbrook (the rest is history, but might be made up), Hadley Freeman (who Marriott quotes in true suck up-style), and Libby Purves who discovers she loves an argument that sounds like her own weekly columns.

The “unrealistic pressure to be ‘special’” is an appealing phantom for Marriott to set off haunting his origami castle, but it’s bollocks. Young people are denied the normality that their parents and grandparents experienced by precarious work and housing conditions, comfortable older generations who often hate them (even if they are their own parents), electoral politics that ignores or criminalises them, and a media that talks constant shit about them.

And when Marriott waffles about being “normal”, he does not define what he means by the word. Normal in 1950? 1969? 1977? 1984? 1990? Now? What is normal and who decides what it constitutes? The answer is, of course, the columnists, their comment editors, their bosses, the proprietors, and anyone else who has a big stake in capital and an interest in protecting it.

In the 1950s, teenagers were a new economic category. In the 1950s, women were not allowed their own bank accounts. In the 1950s, the concept of subsuming the self to the whims of the state was more common but also a generation of men and women had just lived through a brutal war and craved the comfort of a new kind of normality (which with rationing stretching on took a long time to arrive). In the 1950s, the Beatniks prepped the ground for the rock and roll generation to come by saying, “Fuck that.”

The problem with Mariott’s origami castle is the same issue that Samuels’ construction has: Ahistoricism combined with ludicrous confidence. Subject either to a cold rainstorm of analysis or a lukewarm jet of pissy derision and you are left with the same result: A soggy mess.

Thanks for reading. Please share this edition if you liked it (it really helps)…

… and consider upgrading to a paid subscription to get bonuses and make it even more sustainable for me to write this newsletter:

More listening:

Not one of the ‘columnists’ paid to write dull conformist space-fillers for Murdoch’s Times has had the (modest) wit to point out that the true successor to the throne is not Charles at all. It’s Francis of Bavaria, direct descendent of James I. Problem: he’s Catholic, so barred by the Act of Settlement, whose unspoken purpose is to ensure that all those lovely properties stolen from the Church by Henry VIII will never have to be returned by the aristocrats who inherit them today. Francis’s family was anti-Nazi so, incredibly, the lad actually spent years in concentration camps.

About the same time as our king, Edward VIII, was visiting Germany for another reason.

All a bit chancy, even arbitrary, isn’t it.

So what’s all that codswallop about “collective loyalty”?

I may be guilty of taking Marriott out of context - I've not read the whole thing, just the section quoted above - but the conflation of the "side hustle" with the supposed/imagined pressure to be "special" feels particularly unhelpful. When I went to university, it was actually in the rules of the institution that students weren't allowed to have part-time jobs, because they interfered with us being able to focus on our coursework. There was a grey area where working for money for a few hours a week in one of the college libraries was viewed as acceptable, but that was it. Of course, this was in the era of means-tested maintenance grants, and the state paid the course fees - a halcyon and byegone era, and one I remind myself every day to be thankful for having lived through and in. With some creative use of my first credit card, an interest-free student overdraft and the income from those library stints, I was able to enter the world of work without accruing any significant debt. Today's cohort aren't being forced into thinking they're special: they're being forced to work several jobs while in higher education just to try to emerge at the end of the course without amassing the kind of financial burden I didn't have to take on until I bought a house. Mannion looks like he's young enough not to have had the same opportunity I had: but even less reason, then, you'd imagine, for him to not realise that "side hustles" aren't things students dream up as a form of self-aggrandisement, but as a necessary device to help them make it to the end of their course without facing financial ruin. If there's pressure being placed on them to do more and be more, that's not coming from within; it's from a society that has apparently arrived at a position where it places such a low value on education that it thinks of it as some sort of luxury lifestyle choice which should be paid for by the children and young people who are experiencing it, rather than by the whole of that society, despite the benefits to us all of educating our younger people being abundantly, if not head-bangingly, obvious.