The meaning of £20: A majority middle-class media rarely reflects the reality of poverty

It’s not just the stories chosen, but the words used to tell them.

“The reason that the rich were so rich, Vimes reasoned, was because they managed to spend less money.

Take boots, for example. He earned thirty-eight dollars a month plus allowances. A really good pair of leather boots cost fifty dollars. But an affordable pair of boots, which were sort of OK for a season or two and then leaked like hell when the cardboard gave out, cost about ten dollars.Those were the kind of boots Vimes always bought, and wore until the soles were so thin that he could tell where he was in Ankh-Morpork on a foggy night by the feel of the cobbles.

But the thing was that good boots lasted for years and years. A man who could afford fifty dollars had a pair of boots that'd still be keeping his feet dry in ten years' time, while the poor man who could only afford cheap boots would have spent a hundred dollars on boots in the same time and would still have wet feet.

This was the Captain Samuel Vimes 'Boots' theory of socioeconomic unfairness.”

I read Men At Arms, the second of the Guards books in Terry Pratchett’s masterful Discworld series when I was about 11. I had not been personally desperately skint then. I was largely unaware of when my own parents had to scrimp and save and go without. I’d not yet hung around the yellow sticker section like a sickly shark circling in the hope of some blood in the water. Nor spent a long time debating how to spend £10 that needed to last me a week.

I’ve had the luck and good fortune in my life to only have passing periods of being utterly on my arse, but Vimes and his boots have never left me. I thought of them a couple of years ago when I had to sell my bass guitar and records to pay bills, only for an overdue invoice to finally be paid the next week. I still didn’t have the cash to buy my bass back or rescue the records. They were gone.

The value of things distorts. To the rich, £20 is trifling; to someone who’s poor, it can and often is everything.

The current debate over maintaining the so-called “£20 uplift in Universal Credit” or scrapping it in the teeth of an ongoing pandemic is an example of that value distortion in effect. It also illustrates how the language of numbers in the media is always political.

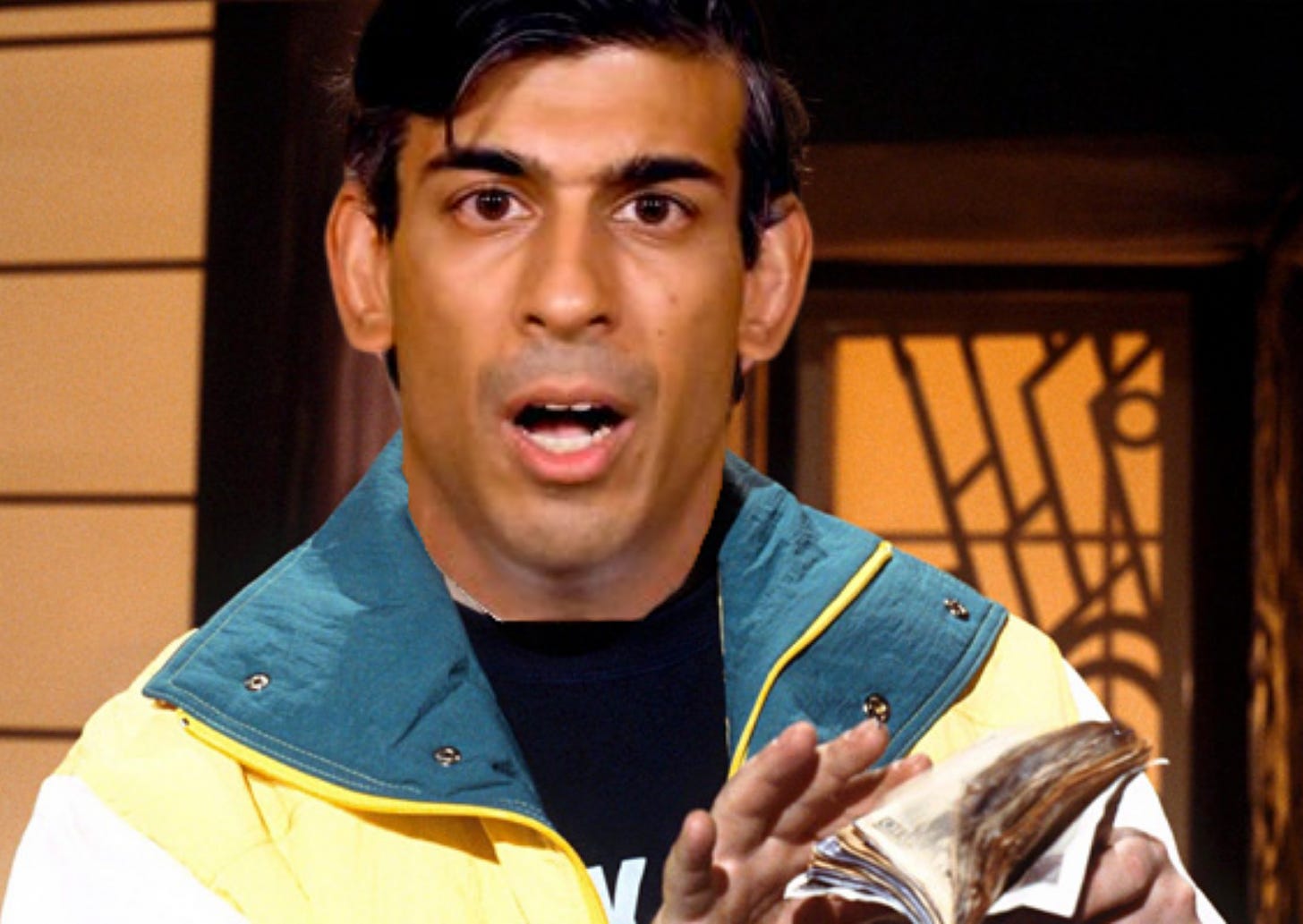

Calling it the “£20 uplift” makes it seem minor to people who aren’t engaged and easier for the ruthless Rishi Sunak to argue for his temporary act of ‘largesse’ — it’s not his money for fuck’s sake — is both not affordable in the long term and not such a big deal to reverse. Explain that taking away the ‘uplift’ actually means taking £1,040 from vulnerable people who desperately need it, forcing 500,000 more people into poverty — 200,000 of them children — lands differently.

Vimes’ Boots come into play in this discussion. The poorest in society are forced to pay more per unit for gas and electricity because they are unable to pay by Direct Debit and are often forced to use prepayment meters which make you pay-as-you-go for heat and light. During lockdowns, many people have been forced to shop more locally, pushed into shops where prices are higher than at larger supermarkets. Being poor is an expensive business.

As my friend Sweyn noted on Twitter, Radio 4’s PM contextualised the value of the ‘uplift’ well — it accounts for around 13% of the total income of the families affected. To lose that is a big deal and while the government is blowing hot and cold — Dominic Raab said the increase is only “temporary” yesterday, while his boss, anthropomorphic bin bag Boris Johnson ‘hinted’ that it may continue — people in desperate situations are wondering if it’s going to get more desperate.

The newspapers — particularly their columnists — often give space to things we can and cannot afford, but where they choose to focus is instructive. We’re never short of pieces in The Daily Mail, The Daily Telegraph, and The Sun cheering huge spending on the military. We simply must have more missiles, warplanes, and exciting new weapons like drones and robots. It’s vital for the international dick-measuring competition we are particularly obsessed with now that Brexit has left us limping, our foot shot to pieces by our own gun.

Trident, tax cuts for the Tory shires, ‘protecting’ statues, £22 billion on a test and trace system that doesn’t work, corrupt payments to off-the-shelf companies selling shoddy PPE, a ‘bridge to Ireland’, HS2… the list of things we can afford is long. But money spent to improve the lives of the poorest in our society is always up for debate, always on the table when “the books have to be balanced”.

Politics is about priorities and whatever the public pronouncements of the Prime Minister and his Cabinet, poverty is never really their priority. Columnists raising ‘legitimate’ questions about the ‘fecklessness’ of those who are struggling, enable governments in getting away with it.

Let’s look at how The Telegraph — one conduit, along with The Times for the government to float policy through sources — frames the cabinet discussions on the issue:

The Daily Telegraph understands a suite of options have now been drawn up, including a gradual winding down of the increase into the new financial year.

… This would prevent another “cliff-edge” occurring later down the line in the event of an extension, which some ministers fear will be used again by Sir Keir Starmer to attack the Government and drive a “wedge” between Mr Johnson and his newer “Red Wall” MPs, who are more sympathetic to Labour’s arguments on welfare…

…It comes after sources told this newspaper last week that there were differences in opinion between the Treasury and Department for Work and Pension over the policy, although sources insist Mr Sunak has not ruled out an extension and is keeping all options on the table.

Alternatively, the Treasury has proposed a lump sum payment, which reports initially suggested would be £500 per claimant, ensuring they continued to receive the same level of support through to October.

However, sources on Monday said could be “more generous” if the economic circumstances warranted it.

Separately, Treasury insiders fired a warning shot to Conservative MPs over the cost of a permanent uplift on the public finances, suggesting that the £6bn annual bill would need to be funded with tax rises.

Floating two potential scenarios, the insiders pointed to a 1p increase in income tax for 30 million taxpayers - translating to £175 for someone earning £30,000 - as well as a 5p hike in fuel duty.

In November, the Johnson government announced a £16 billion increase in military spending over the next four years, bringing the overall bill to over £45 billion a year. The Daily Telegraph’s leader writers did not stroke their bumfluff beards over that cost and wonder if ‘we’ can afford it.

There’s always money for the military in the minds of these childlike chancers still dreaming of war comics. But £6 billion spent on the poorest in society is a stretch too far and must come with warnings of tax increases and an attempt to further force a wedge between the middle and working classes. “Hey! You’re on £30,000 a year and you earn every penny. Why should some workshy dosser get money and cause you to be £175 worse off!”

It’s also interesting that the government is framed as being “generous” when it does anything to help vulnerable people as if they should be grateful that ministers are doling out taxpayers’ money. Remember also that the only ‘taxpayers’ who get spoken up for in the pages of The Daily Telegraph are the ‘taxpayers’ defended by The Taxpayers Alliance, an opaquely-funded think-tank whose real aim is to help a handful of rich people avoid as much tax as possible.

Meanwhile, the Prime Minister talks out of both sides of his mouth, as The Times’ report shows with two quotes in quick succession:

“What we’ve said is we will put our arms around the whole of the country,” [Boris Johnson] said. “I think the UK is capable of staging a very powerful economic recovery but we’ve got to look after people throughout the pandemic. We want to make sure people don’t suffer.”

Mr Johnson’s comments are in marked contrast to his remarks to senior MPs last week, when he said that “most people in this country would rather see a focus on jobs and a growth in wages than focusing on welfare”.

Even the word ‘welfare’ is loaded. Call if ‘help’ or ‘support’ and it’s much harder to slash. Say ‘welfare’ and you are drawing upon images of people who just don’t try hard enough, the false cultural stereotypes of Reagan’s America — ‘welfare queens’ — and The Sun’s beloved bullying phrase “benefits cheats” (in truth, fraud cases are a minuscule issue, accounting for between 0.8% and 1.1% of the total bill depending on who you ask).

The Spectator, whose political editor James Forsyth is an old school friend of the Chancellor Rishi Sunak (they were each other’s best men at their weddings and are godfathers to each other’s children), says:

Chancellor Rishi Sunak is concerned about the hefty price tag of around £6 billion of maintaining the uplift.

Look at that language again — “hefty price tag”. Compare it to spending on defence or the cost of HS2 and it’s a small price to pay. If they were honest, the right-wing press and the government would admit their issue with spending more to help the poor isn’t about price, it’s ideology. The language of ‘tough choices’ is a smokescreen and, as ever, much of the British media stokes the fire.