Losing the tabloid lottery: The Sun turns its glare on a young woman who won a (mis)fortune

There’s a long history of tabloids turning ordinary people into monsters and morality tales.

Callie Rogers should be a footnote but instead, she was a front-page yesterday. She was dragged back into the limelight by The Sun, which has always believed itself to be the ultimate arbiter of public interest, here defined as “things that interest the public”.

Rogers was 16 when she became the UK’s youngest ever lottery winner. She’s now 33 and her £1.8 million jackpot was quite literally half a lifetime ago. But The Sun seems to believe that the simple fact that Rogers is the answer to a trivia question means it can splash her private misfortunes across its front page.

With typical sneering salaciousness, the newspaper accuses her of “blowing” the winnings, notes with all the usual insinuation that she is a mother of four “now on benefits”, and detail her conviction for drug driving with a howling absence of kindness and empathy.

Rogers’ driving offence didn’t hurt anyone else — though it potentially could have — and belongs in court reporting by the local press, if, in fact, it belongs anywhere. Putting her travails in the bright glare of a national newspaper front page simply because she had the (mis)fortune to win the lottery at a record-breaking young age is an act of cruelty.

And when you dig into the details — details printed by The Sun in direct contradiction of its angle — you realise that while Rogers has struggled with the fame that came with her win, she did not “blow” the money. She spent a significant amount of it on others and on things that she thought she needed.

Rogers used a large proportion of the money she won (£550,000) to buy houses for herself, her parents and grandparents, which is hardly squandering it. Another £190,000 said to have been sent on gifts and loans to family and £188,000 in gifts to former boyfriends could be sneered at as The Sun has done or seen as the perhaps unwise generosity of a young woman who had no decent guidance on what to do with an enormous windfall.

The Sun takes until its third page of ‘reporting’ on Rogers before some important context is added to the story:

Ms Rogers has previously told how her £1.87 million lottery jackpot — making her Britain’s youngest lottery winner — plunged her into a cycle of despair. She was targeted by fake pals who took cash off her, endured a string of failed relationships and was brutally attacked because of her win.

What is The Sun doing now but brutally attacking a woman when she’s down? If this were a member of Sun editor Victoria Newton’s family, would she feel it fair or proportionate to have their personal life splashed on the front page of a tabloid because they won the lottery 17 years ago?

In 2018, Rogers was attacked by two women after a night out. She was left unconscious with broken ribs and smashed teeth. The assault left her with permanent sight damage, and her assailants were later jailed. She’s also spoken, when pushed to by the same tabloid press that is now hounding her again, about experiencing depression and called for the National Lottery age limit to be raised to 18. That change in the law is, in fact, now happening as of April 2021.

Back in 2003, when Rogers won the lottery, The Sun’s headline — reproduced in its coverage yesterday — read Girl, 16, Wins £1.8m On Lottery and the subhead declared She’ll take first holiday abroad. I think Rogers has done well to survive such a life-changing event. I’m not sure I would have if I had got my hands on £1.8 million at 16 years old.

But The Sun’s coverage isn’t designed to elicit empathy. Here’s just a couple of examples of how its readers are responding to the story:

“People like her…”

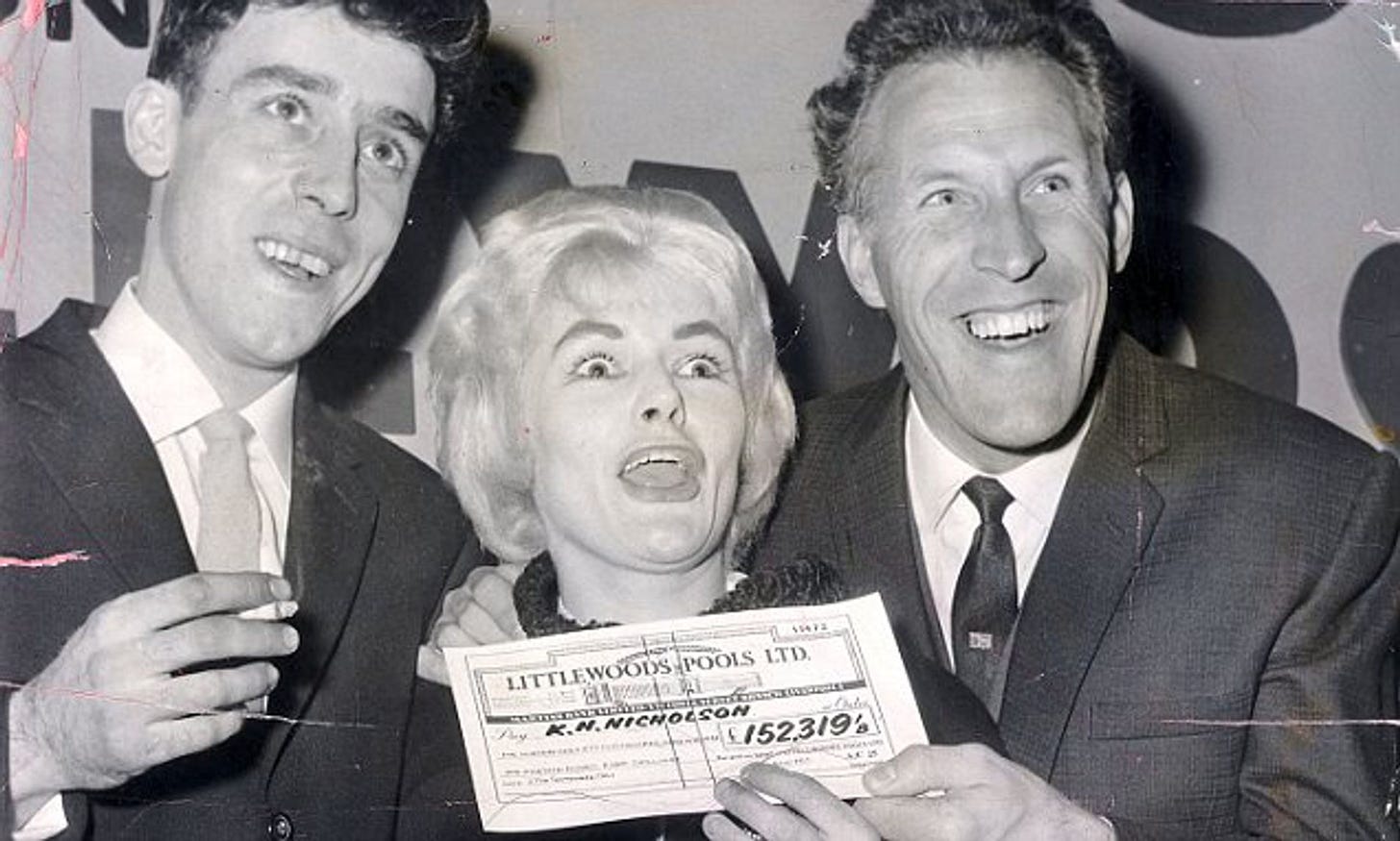

There’s precedent for the tabloid turning on and obsessing about working-class women who win big. The most famous example is Viv Nicholson, who won a fortune on the pools (£152,319 — the equivalent of £3,467,356.13 adjusted for inflation to 2020) and told the press that she was going to “spend, spend, spend”. She did just that and who could blame her?

Nicholson had grown up in extreme poverty, forced to scavenge for coal while looking after her younger brothers and sisters, denied the scholarship at art school that she won, and made to leave school aged 14 to work in a local liquorice factory. She got pregnant at 16 and by 1961, when she won the money, had four children and was on her second husband.

But, as the tediously repeated aphorism has it, money does not buy happiness. Nicholson struggled with the fame that the win brought her, could not control her spending, and faced repeated tragedies and cruelty (her second and third husbands both died in car crashes, her next was an abuser, while her fifth husband died of a drug overdose). As her father had done before her, she struggled with alcoholism until her death.

The newspapers treated Nicholson’s life as a soap opera and a moral lesson to their readers about what happens when you get ideas above your station. The broadsheets were no more immune to scoffing at her than the tabloids. When she died, aged 79 in 2015, The Guardians’ obituary — which was otherwise broadly kind — could not help letting some sneering slip through:

Although money left her as wildly impulsive as did the lakes of alcohol she consumed before she became a Jehovah’s Witness in 1979, she was clever, persevering and deservedly proud to see her children enjoy a much better start and far more encouragement in life than she had had.

… perfect media game, from a poverty-stricken mining background in Castleford, near Wakefield, they had borrowed their stake, almost lost the winning coupon and only made it to the cheque presentation with Viv in her sister’s stockings and shoes. Blonde and gutsy, she teetered on these towards the officiating celeb, Bruce Forsyth, and fainted into his arms.

She and Keith were egged on relentlessly to stick to her spending promise, headlines surrounding every excess. Their bling new home was called Ponderosa after the ranch in a TV series; its swimming pool was often empty and used by the children to store their bikes. Viv bought a pink Cadillac like the one driven by one of her heroines, Jayne Mansfield, and dyed her hair to match. There were binges in the local Miners’ Arms.

The New York Times summed up the British press’ treatment of Nicholson quite neatly in its obituary…

Mrs. Nicholson, widely known as Viv, remained a picaresque fixture of the British tabloids ever after, combining the looks of a gangster’s moll with the larger-than-life temperament of Auntie Mame… she incited in readers successive waves of envy, censoriousness, schadenfreude and, ultimately, awe-struck admiration for her indomitable mien.

… but that last line is rather too kind to the media. Nicholson did not ‘incite’ those feelings in readers, newspaper journalists did — using her as a warning, a talking point, a talisman, and a piñata to beat.

The difference between Rogers and Nicholson is that the latter was at least seen occasionally through the prism of empathy and allowed a measure of glamour. The Sun plastered its front page with a paparazzi picture of Rogers with her hood up and her head down as she walked into court to be sentenced for her involvement in the car crash. On an already terrible day in her life, the tabloids were there to make sure it was much worse.

You can be certain that The Sun or one of the other tabloids that have covered the story in the wake of their rival's front page will sidle up to Callie Rogers with the offer of some cash in exchange for a ‘tell-all interview’ and that those same tabloids will jump to it the next time something happens in her life. The media will continue to talk about the ‘curse’ of the lottery win without ever acknowledging that they are the curse.

If you’re a paid subscriber, you’ll receive the weekly edition of Saturday Night/Sunday Warning with article recommendations, behind-the-scenes details on next week’s newsletter topics, and more tonight.

If you’re not, just click the button below to upgrade 👇