Journalism is poorer without Sir Harry Evans and Parliament is poorer without Dennis Skinner

Honest voices. Harsh voices. Strong voices. We need them more than ever and we can have their like again.

“We won’t see their like again,” is a cop-out muttered by the cowardly, the supine and the corrupt. We choose whose like we lift up to the heights and whose we leave to shout out on the sidelines. In the dismal December election of 2019, Dennis Skinner lost his seat. In the grim gloaming of late-September 2020, Sir Harry Evans lost his life. In both events, we lost something precious.

Sir Harold Evans was the soul of investigative journalism in the British tradition. Dennis Skinner was the last survivor of a working-class tradition of MPs who rose from the pits or swam in from the trawlers or the merchant navy, Others took knighthoods, a move that is not a reward for a left-winger, but a castration, a neutering, a pat on the head and a piece of tape across the mouth. But Dennis Skinner remained in place, an embuggerance to the expensively besuited bastards of the Blair years that have stretched long past that war criminal’s term in government.

I write this as a minor rebel, the sort of person likely to be a footnote on a footnote on a footnote, referenced — as I already am — in Wikipedia articles as a source from articles I wrote on one obscure thing or another. I have written investigations that have exposed corruption in recruitment and discovered an unrepentant paedophile at work on Twitter. I have quit jobs just in time to avoid being fired.

But I am the very model of potential halted — a young meteor in staff jobs at Stuff and Q, whose gob and inability to tip the hat to executives who wanted deference has meant that I’ve plied my trade on the outer rim of the galaxy of British media since 2009 with trips to the centre (stints at The Daily Telegraph and The Next Web) since then.

I include that autobiographical diversion for one reason: To explain that I am not directly or indirectly placing myself in the lineage of people like Evans and Skinner, men who in their different ways changed their lines of work for the better. I am over here in this Substack corner trying to agitate for change in my trade, the filthy stinking trench of journalism, but I realise that I have by dint of that shouting made myself unplayable to most of that trade.

Those people in journalism who dislike me tell me often that I am carping because I am not wanted. Sometimes, in anonymous emails sent from anonymous accounts at the most anonymous hours of the early morning, they tell me rather more unpleasant things and wish that I would fuck off and, if possible, die while I’m doing it.

The power of both Evans and Skinner — I hesitate to use the past tense too much as Dennis Skinner is still vibrantly alive — was that they both found their way to places within the system while being able to shake the bars and effect change in a myriad of different ways. Skinner spent decades unswayed by the baubles available to those who take high office but speaking loudly, forcefully and directly on behalf of his constituents but also the working class in general.

Evans, also a product of the working class — born in Eccles, Greater Manchester to parents who were what he described in his autobiography part of “the self-consciously respectable working class".

Unlike Skinner, Evans made himself part of the establishment. He went from the local press, where he led incredible investigations and campaigns, including one around the early days of cancer screening that led to the government finally bringing in checks that have saved thousands upon thousands of women who might have died from cervical cancer to editor of The Sunday Times then The Times, and finally to America for a long, long third act where he became the conscience of good journalists across the west. He also took the knighthood but being someone whose politics were those of the inquisitive hack rather than the chivvying political operator, it did not blunt his sword.

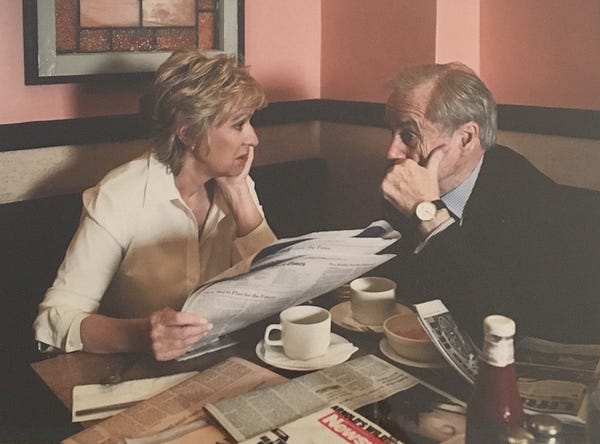

I’m not going to quote Sir Harry extensively here. There are lots of excellent interviews and obituaries to read. He also wrote many books you should buy. However, having written recently about the fact that our so-called ‘free press’ is not free, I wanted to share this quote from his 2009 interview with then Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger:

"It's such a relief to work in the US. With my book, going through the legal flaws and pitfalls in the US took me I think probably from 2 o'clock to 2.45 with the lawyer on the phone. Going through it in the United Kingdom with very intelligent and helpful lawyers took several days."

Evans changed the world for the better. Watch the film Attacking the Devil, which is available on Netflix to understand how. He was ferocious in pursuing the injustices and evils perpetrated against mothers who were encouraged to take Thalidomide, fathers who fought for justice along with them, and their children who were scarred from birth due to the malfeasance of drug companies and governments.

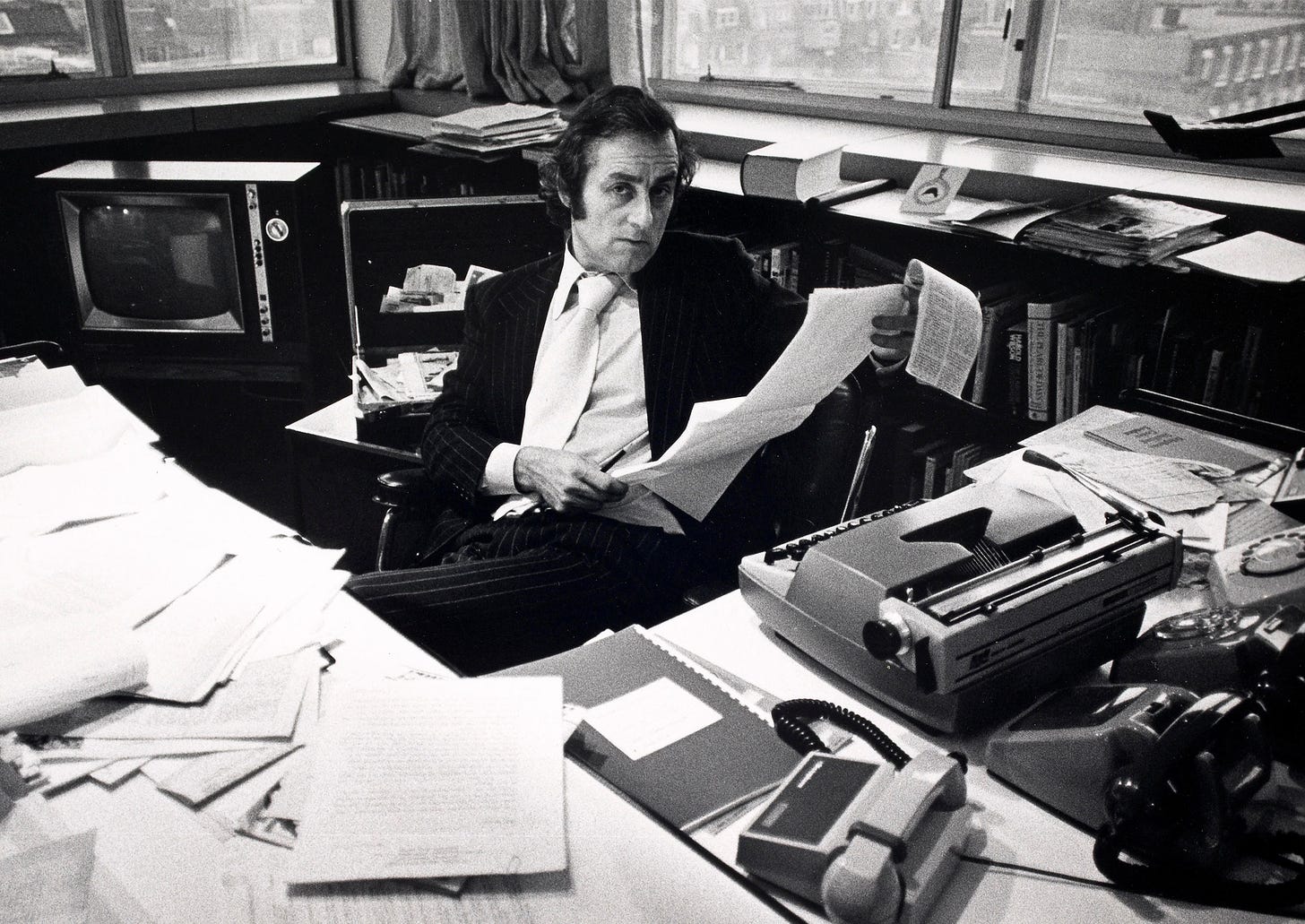

Here’s a clip that didn’t make it into that film, telling the story of why Sir Harry left The Times after clashes with Rupert Murdoch. It was an experience that he reflected upon and spoke about for the rest of his life, making him one of the most eloquent critics of Murdoch’s often malign influence:

Dennis Skinner, who is 88, is still with us. He is still going and still fighting. Here’s an interview he gave a few years ago that is worth your time:

And if you want Skinner’s words, deeds, and legacy to be celebrated, consider buying the new single about him ‘Tony Skinner’s Lad’. Proceeds from the song are going to the Orgreave Truth and Justice Fund.