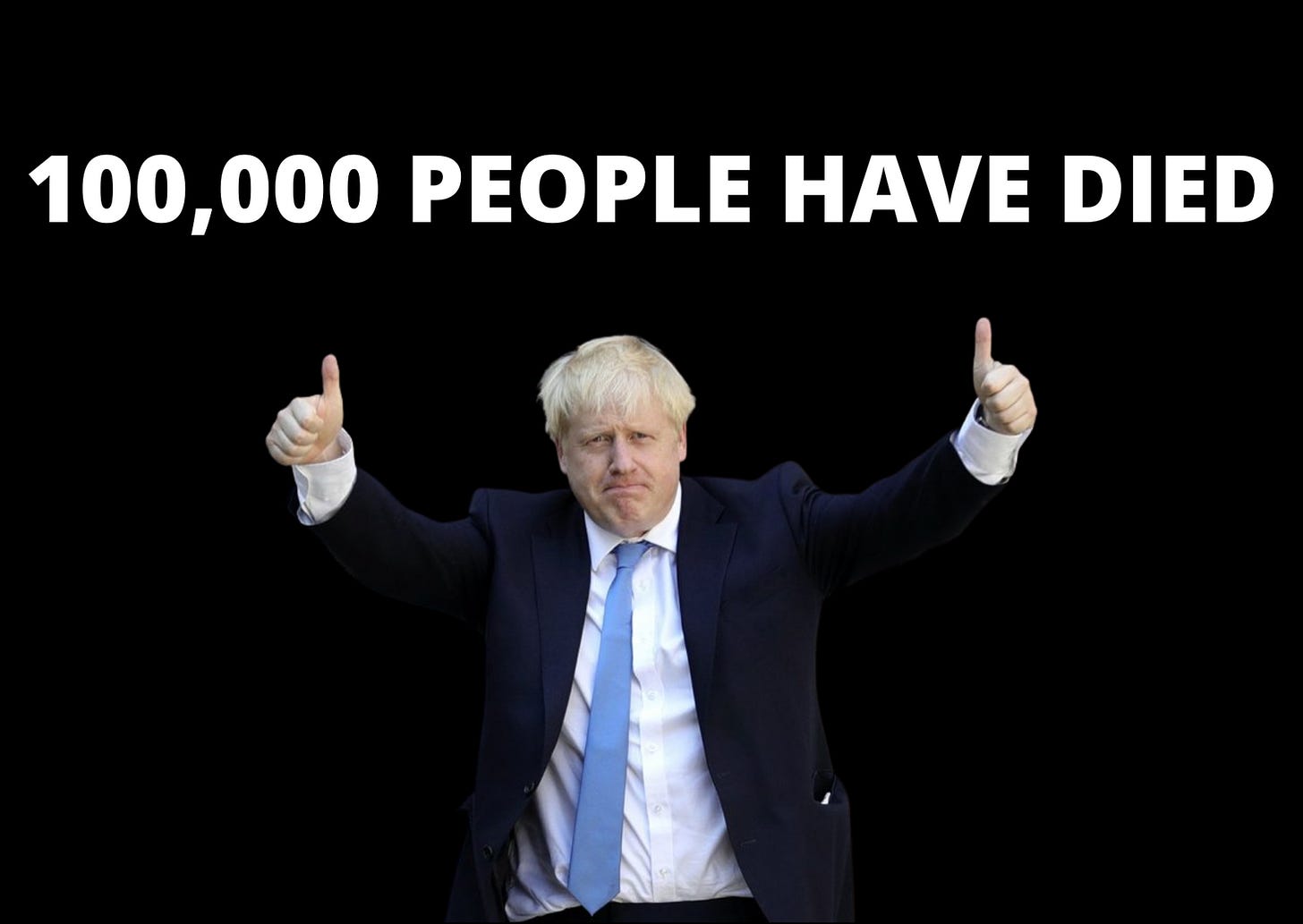

100,000 ghosts: The British media should be haunted by its pandemic failures and the excuses it has made

Insert joke to counteract the bleak mood here.

The playbook is clear: Talk death figures and data; If you don’t make it explicitly about people, it’s possible to abstract the horror out a little. Muddy the water further with discussions of ‘pre-existing conditions’ as if those people were living under the sword anyway and it was somehow inevitable. Whatever you do, don’t link the human interest pieces you run — the stories of families ripped to shreds by an early and unexpected death — with those figures you read out as if they are from a lottery machine, random and inexplicable.

Two segments on last night’s edition of Radio 4’s PM typified the general failure of British newspapers and broadcast media to do their job during this crisis. I switched on the radio just moments after the Prime Minister, his clown face stretched into a parody of grief, announced that 100,000 people in the UK have died since the pandemic began. Evan Davis was talking to Dorothy Duffy, whose sister died of Covid-19. Near the end of the interview this exchange took place:

Evan Davis: “You told us your sister isn’t a statistic. Every day we give the statistics. It would be a dereliction of our journalistic responsibility to not to keep count and to tell people how many are dying in this epidemic… what can we do so that people are not statistics?”

Dorothy Duffy: “In the early days, I watched the news every night… we were all trying to grapple with the reality of this new world. I listened to the way the platitudes and phrases were being bandied about, such as ‘squashing the sombrero’ and ‘flattening the curve’ and I found that quite disrespectful… it’s too easy sometimes to give a daily tally of deaths because it can be desensitising… maybe say 100,000 people have died… each one of those numbers is an individual. There has been so much recently about the R number going up. I was thinking about G for the Grief number. It’s exponential… it can’t be reduced to statistics… bring the word ‘people’ into it.”

Davis wrapped up the segment by saying what he described as a ‘small tweak’ to the language was a good idea. He meant no harm but at that moment I was enraged by the broadcast; how could the notion that saying ‘people’ and not ‘deaths’ would be better be such a lightbulb moment for him?

So much of the reporting and commentary during the pandemic has been rote, pulling from the same frameworks and tactics that were deployed in the General Election that concluded just a month before the news began to filter out of Wuhan about a virus that was of some concern.

Over a year on, with 100,000 people gone and many people still dying, too many journalists are still taking tidbits from anonymous sources, still giving their favoured politicos the benefit of the doubt, still framing the blame on the public more than the incompetent cabinet who brought us to the macabre ‘milestone’ as so many reports last night insisted on calling it.

Yes, there has been powerful reporting from health correspondents and great clarity from the best of the science reporters. And yes, there have been investigations that exposed the pervasive corruption in the PPE procurement processes, the chaos of the exam algorithms, and the cruelty of the school meal parcels. But — and that ‘but’ is 50ft and flashing in red neon — the good has been drowned out by the bad; by both the naive and the noxious.

Even newspapers that have run revelatory investigations into the government’s combination of corruption and incompetence have also splashed with front pages promising false hope or accepting fantasy and fabrication spun out from an administration led by a people-pleasing charlatan.

Journalists often circle the wagons quicker than the cast of a John Wayne movie. They’ll run to their old redoubts — “We speak truth to power!”, “We challenge the government!” — but by and large it’s theatre. Investigations and revelations only work when the pressure is sustained, when the full force of the media storm is focused on an issue not just for days but for weeks, months or even years. Sir Harold Evans, who died last year, did not — along with his team — break the Thalidomide scandal open in a single story. Watergate wasn’t the product of one front page and a scattering of outraged op-eds.

Every newspaper front page that heralded ‘Independence Day’ last summer when the first lockdown was eased, every headline that passed on the government’s message that people should get back to offices, every report that passed on demands from bloviating backbenchers and astroturfing groups of suddenly ‘militant’ mums contributed in its own way to reaching that number that is so abstracted in today’s newspapers — 100,000 people have died.

Every puff piece about Boris Johnson and his cute little family, every shot of his future mother-in-law coming to Downing Street, every photo spread about their dog, every column that made excuses for Dominic Cummings, sneered at ‘hipster analysis’ in the early days of this avoidable disaster, or told us about ‘Dishy’ Rishi and how much he cares, contributed to 100,000 people dead.

Every jingoistic throwback pun to a war that none of us fought and to a history that most people misremember contributed to 100,000 people dead, ever ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ promo plastered on a tabloid front-page, every syllable uttered by political hyena Matt Chorley played its part, every Rod Liddle column, every Fraser Nelson quote, every Sarah Vine column oscillating between bafflement at government policy and insidery snideness, every story that poured more shame on celebrities and influencers than the government that got us here shares a piece of the blame.

And the tellers of truth to power? How many of them are calling for Boris Johnson to resign? How many editors using their front pages and their columns and their investigative reporters to put sustained and serious pressure on a government of incompetents, liars, and crooks? How many are honestly dissecting the piss poor parody of opposition offered by Sir Keir Starmer and his front-bench of boil-in-the-bag Blairites?

Later in yesterday’s edition of PM came the second segment that left me shaking my head with tears in my eyes. It was an interview with a father about his wife who died of Covid-19 aged 50. He was joined by his eldest son in remembering the beauty, kindness and compassion of a woman who should not have died. A sentence in Evan Davis’ introduction that made me angry:

“Her youngest son brought Covid back from school and passed it on to her…”

The boy wasn’t to blame, but that framing — lazily rather than maliciously done — makes it sound as though he is. There have been many, many chin-stroking debates and over-heated monologues on talk radio stations about why the government sent children back into schools and whether schools are safe or not.

When Gavin Williamson — Frank Spencer with a House of Cards boxset — is next on the radio or TV and spouts his practised line, “Schools are safe,” he should have the names and fates of people who have died after Covid-19 came home like a crumpled letter in a kid’s school bag recounted to him rather than some carefully constructed ‘gotcha’ question that he’ll just duck and evade.

Like so many of the sociopaths and charlatans that have occupied the office of Prime Minister before him, Boris Johnson assured us yesterday that “lessons will be learned” and that an inquiry will get to the bottom of how 100,000 people died on his watch, needlessly, senselessly, tragically. But governments choose the lessons they learn and they are never the ones that end with the guilty in jail and justice for those who have suffered.

No, the lesson that Boris Johnson will ‘learn’ is the same one that Tony Blair, George W. Bush, Peter Mandelson, Alastair Campbell and so many others took away from their time wrecking the world — stick around long enough and people will forget. Today, after the counter ticked over to over 100,000 people dead, it seems unfeasible that Boris Johnson will get away with it, but he will. Why? Because we live in a world where Henry Kissinger remains not dead, Tony Blair was a peace envoy, George W. Bush is now a ‘respected elder statesman’, and Alastair Campbell lectures people on mental health.